![]() Click to view article in PDF format.

Click to view article in PDF format.

GCEuler Curvature Helps Define Lineaments*

Satinder Chopra1 and Kurt J. Marfurt2

Search and Discovery Article #40838 (2011)

Posted December 12, 2011

*Adapted from the Geophysical Corner column, prepared by the authors, in AAPG Explorer, December, 2011, and entitled “Euler Curvature Can Be a Calculated Success”. Editor of Geophysical Corner is Bob A. Hardage ([email protected]). Managing Editor of AAPG Explorer is Vern Stefanic; Larry Nation is Communications Director.

1 Arcis Corp., Calgary, Canada ([email protected])

2 University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma

Several (12, we think) types of seismic-based curvature attributes have been introduced the last few years – and of these, the most-positive and the most-negative curvatures described in last month’s article are the most popular. Most-positive and most-negative curvatures provide more continuous maps of faults and flexures than do maximum and minimum curvatures, because the latter tend to rapidly change algebraic sign at fault and flexure intersections.

Other attributes, such as mean curvature, Gaussian curvature and shape index, also have been used by a few practitioners. We describe here a technique called Euler curvature, which has valuable applications.

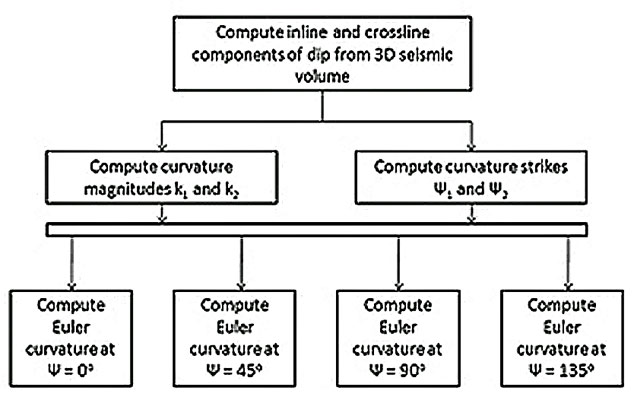

An attraction of Euler curvature is that it can be calculated in any desired azimuth across a 3-D volume to enhance the definition of specific lineaments. When this apparent curvature (the Euler curvature) is computed in several specific azimuths, the results are quite useful for interpreting azimuth-dependent structure. The flow diagram in Figure 1 explains the method for computing azimuth-dependent Euler curvature.

|

|

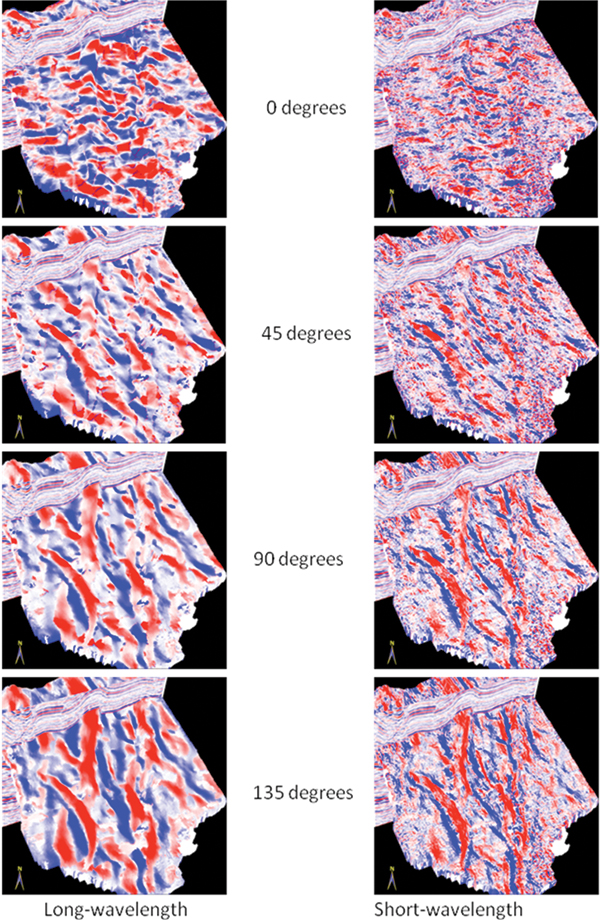

Mapping the intensities of fracture sets has been a major objective of reflection seismologists. Curvature, acoustic impedance and reflection coherence currently are the most effective attributes used to predict fractures in post-stack seismic data. We describe here the application of Euler curvature to a 3-D seismic volume from northeast British Columbia, Canada. We use an interactive workflow to utilize Euler curvature much as we do in generating a suite of shaded relief maps. Figure 2 shows 3-D chair displays through volumes of Euler curvature calculated at azimuths of 0, 45, 90 and 135 degrees from north. The left column shows long-wavelength curvature calculations, and the right column displays short-wavelength calculations. Notice how east-west lineaments stand out when north-south curvature is estimated (azimuth = 0):

The analysis area shown in these figures spans approximately 100 square kilometers. As emphasized in last month’s article, short-wavelength displays show more lineament detail and resolution than do long-wavelength displays. That principle is illustrated again by the displays in Figure 2. The important concept presented here is that there are obvious advantages in calculating Euler curvature on post-stack seismic volumes, because azimuth directions of curvature can be chosen to highlight lineaments in preferred directions. Euler curvatures calculated in desired azimuthal directions produce better definitions of targeted lineaments. Depending on the desired level of detail, either long-wavelength or short-wavelength estimates can be calculated. Short-wavelength Euler curvature would be more beneficial for observing fracture lineaments. This work is in progress, and we hope to calibrate seismic-based lineaments determined with this technology with lineaments interpreted from image logs. We thank Arcis Corporation for permission to show the data examples, as well as for the permission to publish this work.

Copyright © AAPG. Serial rights given by author. For all other rights contact author directly. |

General statement

General statement