Click to view this article in PDF format.

Value

of Applied Research and Future of Natural Gas Supply:

How the U.S. Natural Gas Production Curve Was Built

and How It Will Be Sustained in the Future

Scott W. Tinker and Eugene M. Kim

Bureau

of Economic Geology

The University of Texas at Austin

This article, which is posted also at Bureau of Economic Geology’s website, http://www.beg.utexas.edu, represents a combination of two talks given by the authors--The Value of Upstream Technology and the Future of Applied Research, by the senior author in the period from October, 2000, to June, 2001, and U.S. and Texas Gas Supply: Where We Are Now and Where We Are Headed? by both authors in February, 2001. Appreciation is expressed to B.E.G. and to Dr. Tinker for permission to present the article here.

|

tProduction as a Metric for Research Value

t tMeeting Future U.S.

tProduction as a Metric for Research Value

t tMeeting Future U.S.

tProduction as a Metric for Research Value

t |

Natural

gas is the

Technology is a word that has become so overused that it actually means very little without some context. A geologist might think of 3-D models, a petrophysicist, logging tools, a geophysicist, waves, a reservoir engineer, numerical simulation, an operations engineer, drilling and completions, and a manager might consider the leverage that technology provides on Wall Street. The word means many things to many people. In fact, all of these definitions are important, all are correct, and all are useful within a known context. One thing is certain: technology does not equal wisdom, and technology alone does not add value. A company needs both profit and value to survive over the long run. I consider value to be a longer-term attribute than profit, which carries a fiscal quarter connotation. In the descriptive, interpretive, research-oriented upstream-upstream world of the geologist, geophysicist, and petrophysicist, it is considerably more difficult to quantify value than in the quantified, blueprint, application-oriented downstream-upstream world of the operations engineer

(Figure 1). Value is difficult to quantify in the upstream-upstream, and it is therefore difficult to assign, because it is far removed from the point where Many major In actuality, true research is represented by long periods of normalcy with no apparent progress or results, which are punctuated by moments of brilliance and significant breakthrough. As such, research does not lend itself to quarterly profit evaluation. In fact, today's research often becomes tomorrow's technology application. An Quantifying the value of research is an age-old dilemma. What is the value of knowing that seismic amplitude reflectors and depositional time lines are not always synonymous

(Figure 2)? What is the value of quantifying and visualizing the physical forward model that produced complex salt tectonics

(Figure 3)? What is the value of very rapid acquisition of topographic data and mapping with sub-meter vertical accuracy

(Figure 4)? What is the value of 3-D visualization and of the virtual reality presentation of data to landowners in South Texas

(Figure 5)? What is the value of mapping the salinization variations of soil and ground water around Most industries recognize the importance of technology and innovation

(Figure 8) as a |

|

tProduction as a Metric for Research Value

t tMeeting Future U.S.

tProduction as a Metric for Research Value

t tMeeting Future U.S.

tProduction as a Metric for Research Value

t tMeeting Future U.S.

tProduction as a Metric for Research Value

t |

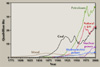

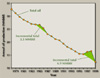

Figure Captions--Production as a Metric for Research Value

Production as a Metric for Research Value Until the late 1800's, wood was the primary The University of Texas owns One possibility is that the humps are related to exploration and development driven by Another possibility is that University Lands Natural gas production in the United States was able to keep pace with consumption until the mid-1980's (Figure 19). Natural gas imports have risen from around 4% in the mid-1980's to more than 15% today (Figure 20). More than 3 Tcf of gas was imported in 2000, and that number is not anticipated to decrease. A large percentage of the U.S. imported pipeline natural gas comes from Canada. Liquefied natural gas (LNG), largely from Algeria and Trinidad (Figure 21), accounts for most of the remaining natural gas imports. Forecasts for annual U.S. natural gas production indicate natural gas supply will grow from 21 Tcf in 2001 to around 27 Tcf by 2015. Demand is projected to exceed 30 Tcf by 2015 (Figure 22). Whereas most of the U.S. natural gas to date has come from associated, high-permeability, and shallow offshore sources, around 50% of the produced natural gas in 2015 is forecast to come from deepwater, subsalt, and unconventional (tight gas, shale gas, and coalbed methane) sources. Analysis of historical Federal and State exploration incentive programs and Federal and private investment in unconventional natural gas research indicates that the supply curves benefited greatly from natural gas research and the successful application of technology. The tight gas production curve shows a large positive increase in slope in 1985 following $165 million of combined investment in research by the DOE and GRI (Figure 23). Studies were focused on advanced stimulation technology, the greater Green River Basin, and the Piceance Basin. Combined with Federal and State tight gas production incentives, and investments in exploration and production by private sector operators, these investments in research have produced 11 Tcf of incremental natural gas to date. The shale gas production curve shows a large positive increase in slope also in 1985 following more than $90 million of investment in research by the DOE in the prior decade (Figure 24). Another surge in production from shale gas followed $6 million of additional investment by GRI beginning in 1990. Studies were focused on the Antrim shales and the Appalachian Basin shales. Combined with investments in exploration and production by private sector operators, these investments in research have produced more than 2 Tcf of incremental natural gas to date. The coalbed methane production curve shows a large positive increase in slope in the late 1980's following $82 million of combined investment in research by the DOE and GRI in the preceding decade (Figure 25). Combined with Federal and State production incentives, and investments in exploration and production by private sector operators, these investments in research have produced nearly 5 Tcf of incremental natural gas to date, and show no evidence of slowing as coalbed methane expands its productive horizons to Texas. To summarize, Federal and State production incentives, combined with tight gas, shale gas, and coalbed methane research, funded largely by the U.S. Department of |

|

tProduction as a Metric for Research Value

t tMeeting Future U.S.

tProduction as a Metric for Research Value

t tMeeting Future U.S.

tProduction as a Metric for Research Value

t |

Figure Captions--Meeting Future U.S.

Meeting Future U.S. Production

Part of the U.S. natural gas supply will continue to be satisfied by imported natural gas from Canada. Although Mexico currently consumes an order of magnitude less natural gas than the United States (<2 Tcf vs. >21 Tcf), demand for natural gas in Mexico is forecast to increase considerably over the next decade. Several of the Gulf onshore basins in Mexico, including Burgos, Veracruz, and Macuspana, and the underexplored Mexico offshore have high natural gas potential. However, because demand for natural gas within Mexico is growing dramatically, it is unlikely that Mexico will become a net exporter of natural gas to the United States in the short or mid term. To fill the demand gap, imported LNG must continue to rise over the next decade. The United States is facing a very real In fact, just the opposite is true: the United States has been on " The mega-merger frenzy has resulted in several market realities. There has been a significant reduction in earth scientists and petroleum engineers over the past decade, resulting in very "lean" technical staff within each company. Graduate students in universities have recognized this shrinking job market and are now choosing other disciplines. Finally, there has been an extreme divergence in "economic class" between the super-majors and everyone else, which is unhealthy for the long-term survival of the industry. The American people must make a decision regarding fossil In addition to Federal investment in fossil Key elements of PERF: Key benefits of PERF: Research and the creative application of technology helped build the The United States has an

Kim, E. M., Tinker, S. W., Fisher, W. L., and Ruppel, S. C., 2000, Benefit/cost analysis of GRI's gas supply research initiative: economics of a gas supply research trust fund to increase gas production of Federal lands: The University of Texas at Austin, Bureau of Economic Geology, final report prepared for Gas Research Institute, 70 p. |