![]() Click to view page images in PDF format.

Click to view page images in PDF format.

LIBYA:

PETROLEUM POTENTIAL OF THE UNDEREXPLORED  BASIN

BASIN CENTERS—A

TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY

CHALLENGE*

CENTERS—A

TWENTY-FIRST-CENTURY

CHALLENGE*

By

Donald C. Rusk1

Search and Discovery Article #10025 (2002)

*Online version of article with same title by same author in AAPG Memoir 74, Sedimentary Provinces of Twenty-first Century, available for sale at http://bookstore.aapg.org.

1Consultant, Houston, Texas, U.S.A. ([email protected]).

Recoverable

reserves in approximately 320 fields in Libya’s Sirt, Ghadamis, Murzuq, and

Tripolitania Basins exceed 50 billion barrels of  oil

oil and 40 trillion cubic feet

of gas. Approximately 80% of these reserves were discovered prior to 1970. Since

then, there has been a less active and more conservative exploration effort.

Complex, subtle and, in particular, deep plays were rarely pursued during the

1970s and 1980s because of definitive imaging technologies, limited knowledge of

the petroleum systems, high costs, and risk adversity.

and 40 trillion cubic feet

of gas. Approximately 80% of these reserves were discovered prior to 1970. Since

then, there has been a less active and more conservative exploration effort.

Complex, subtle and, in particular, deep plays were rarely pursued during the

1970s and 1980s because of definitive imaging technologies, limited knowledge of

the petroleum systems, high costs, and risk adversity.

Consequently, extensive undiscovered resources remain in Libya. These resources could be accessed if geologic and geophysical knowledge, innovation, and advanced technologies were used effectively. Three-dimensional seismic acquisition will be required to some degree for reliable trap definition and stratigraphic control.

Predictably, most of

the undiscovered resources will be found in the vast, under-explored deep areas

of the producing basins. Six areas are exceptional in this regard: the south

Ajdabiya trough, the central Maradah graben, and the south Zallah trough–Tumayam

trough in the Sirt  Basin

Basin , and the central Ghadamis

, and the central Ghadamis  Basin

Basin , the central Murzuq

, the central Murzuq

Basin

Basin , and the offshore eastern Tripolitania

, and the offshore eastern Tripolitania  Basin

Basin in the west. These highly

prospective

in the west. These highly

prospective  basin

basin sectors encompass a total area of nearly 150,000 km2, with an average well density for wells

exceeding 12,000 ft of 1 well/5000 km2.

sectors encompass a total area of nearly 150,000 km2, with an average well density for wells

exceeding 12,000 ft of 1 well/5000 km2.

|

|

Click here for sequence of figures 2 and 7.

Click here for sequence of figures 6, 5, 4, and 10.

Click here for sequence of figures 6, 5, 4, and 10.

Click here for sequence of figures 6, 5, 4, and 10.

Click here for sequence of figures 2 and 7.

Click here for sequence of figures 6, 5, 4, and 10.

Click here for sequence of figures 13, 17, and 16.

Click here for sequence of figures 13, 17, and 16.

Click here for sequence of figures 13, 17, and 16.

Click here for sequence of figures 19 and 21.

Click here for sequence of figures 19 and 21.

The

exploration effort in Libya, which began in 1957,

has been a phenomenal success. In the Sirt Despite

this great exploration effort, the four producing basins are in the

emerging stage of exploration maturity. Two aspects in particular are

indicative of vast undiscovered resources in Libya and the exploration

opportunities to access those resources: (1) numerous potential areas,

proximal to It

is noteworthy that 17 of the 21 giant Complex and subtle plays (for example, low-relief structural or structural-stratigraphic traps and deep plays) were rarely pursued prior to the 1990s. Probably the main reasons for the absence of an aggressive approach to exploration in the 1970–1990 period were lack of definitive imaging technologies (seismic acquisition and processing and other computer-related geoscience technology), limited understanding of petroleum systems, and ineffective use of sequence-stratigraphic concepts. Today, in view of state-of-the-art technologies available for a wide range of petroleum-exploration needs and the relatively low cost to apply them, pursuit of deep plays in Libya should be a top priority. To address this objective, I have selected for evaluation six large underexplored areas with exceptional potential and, for the most part, with deep primary targets (Figure 1). However, many other promising areas are within and near the producing basins of Libya. Three

of the subject areas are in the Sirt

Deposition

of mostly continental siliciclastics during the Cambrian and marginally

marine to marine siliciclastics during the Ordovician and Silurian

continued essentially without interruption from Morocco to the Middle

East. Uplift and erosion during the Late Silurian Caledonian orogeny

initially defined the limits of the Paleozoic basins of Libya. The

east-west-trending Qarqaf arch separated the Ghadamis and Murzuq Basins;

the north-south-trending Sirt-Tibesti arch separated the Murzuq and

Kufrah Basins and, generally, the Ghadamis After

the dominantly marine siliciclastic deposition during the Devonian and

the shallow-marine to continental deposition in the Carboniferous,

widespread uplift and severe erosion during the Hercynian orogeny,

particularly along the Sirt-Tibesti arch, Qarqaf arch, and Jefara

uplift, further accentuated the Paleozoic

A

very thick sequence of continental sediments of Triassic to Early

Cretaceous age occupies the central part of Murzuq This

resulted in a more pronounced northward increase in sedimentary

thickness, with increased marine influence. This Mesozoic depositional

episode continued offshore in the Tripolitania In

the general area of the future Sirt Nubian deposition was controlled by surface relief and, to some degree, by faulting. In the Albian or early Cenomanian, extensional and probably transtensional faulting, followed by uplift and erosion, deformed the Sirt-Tibesti arch. This activity (the Sirt event) was a prelude to subsequent collapse of the arch (El-Alami, 1996b; Gras, 1996; Hallett and El-Ghoul, 1996; Koscec and Gherryo, 1996). The structural alignment created, which is most evident in the south and southeast, was for the most part east-west, east-south-east–west-northwest, and east-northeast–west-southwest. Consequently, the subcrop at the Sirt unconformity is a mosaic of Jurassic to Lower Cretaceous siliciclastics in grabens and half grabens, which are in depositional or fault contact with basement or Cambrian-Ordovician rocks on structural highs. Evidence of this fabric is exhibited in the Faregh, Masrab, Magid, Messlah, Jalu, and other areas in the southeast sector and is suggested by fault trends in the southern parts of the Zaltan and Bayda platforms. The

main Sirt

In

the northern sector of the Ghadamis In

the Sirt

The

petroleum systems, which have been active in the six

The

underexplored sectors of the Ajdabiya trough, Maradah graben, and

Zallah-Tumayam trough have important features in common: nearby

Source-rock Summary (Figure 3) The Campanian-Coniacian Sirt-Rachmat shale sequence, which includes minor amounts of carbonates (Tagrifet limestone) with variable source potential, varies in thickness from 1000 ft to more than 3000 ft in each of the three troughs (Figure 4). The total organic carbon (TOC) of this sequence ranges from 0.5% to 8%, averaging 1.5–4% (Parsons et al., 1980; Hamyouni et al., 1984; Baric et al., 1996). The Cenomanian-Turonian Etel Formation (evaporites, shale, and minor carbonates deposited in shallow lagoonal to supratidal conditions) exhibits good source-rock characteristics, with TOC ranging from 0.6% to 6.5% in the Hameimat trough (El-Alami, 1996b). These same Etel facies, with net shale thicknesses of 200 ft to more than 1000 ft, are present in the southern Ajdabiya trough and Maradah graben (Figure 5). Therefore, they should be considered an effective source in those sectors. The source quality of the Etel shale is questionable in the southern Zallah and Tumayam troughs, where it exceeds 500 ft in a limited area only. A third source is the Lower Cretaceous middle shale member of the Nubian Formation. Nubian lacustrine to lagoonal shale has been identified in the Hameimat trough and the adjoining Faregh and Messlah areas, where thicknesses vary from 0 to 1000 ft (Figure 6) and average TOC is approximately 3%. It is most likely a minor source in the southern part of the Ajdabiya trough. In the Maradah graben, based on only two wells (El-Hawat, 1996), the Nubian middle variegated shale member attains thicknesses ranging from 200 to 400 ft. This shale sequence was deposited in a partially anoxic, marginal-marine environment. It

may have contributed some hydrocarbon to surrounding areas. The

contribution of variable quantities of

Reservoirs.—The lower and upper sandstone members of the Upper Jurassic to Lower Cretaceous Nubian Formation are clearly the primary reservoir targets for the area (Clifford et al., 1980; Ibrahim, 1991; Abdulgader, 1996; Mansour and Magairhy, 1996). Net sand thicknesses are estimated to range from 0 (at discrete onlap and truncation limits) to 1200 ft (Figure 6). Depth to the top Nubian ranges from 12,000 to 18,000 ft (Figure 7). Despite these depths, it is expected that average porosities will be 12–13%, with maximum porosity exceeding 20%. Average porosity at depths below 15,000 ft ranges from 12% to 13.5% in some wells in nearby Hameimat trough. Secondary

reservoir objectives are high risk in the area because of limited

distribution and reservoir properties. The Bahi (Maragh) sandstone

equivalent is absent or very thin in surrounding areas, with dominant

siltstone and shale lithology suggestive of the Etel Formation. The

Lidam dolomite, a facies of the Etel Formation in this sector of the

Sirt Possible attractive secondary targets are Paleocene lower and upper Sabil shoal and reef limestones (Spring and Hansen, 1998). Upper Sabil shelf-edge deposition was not controlled by rift phase faulting, and the shelf extended across the southern part of the Ajdabiya trough (Figure 8). This potential reservoir is at relatively shallow depths and consequently has been the subject of exploration programs for some time. However, subtle buildups, overlooked in the past, can be imaged accurately today using state-of-the-art methods. Seals.—Etel

shale and anhydrite at the Sirt unconformity provide an effective seal

for the Nubian sandstone throughout most of the area. Locally, a thin

Bahi (Maragh) sandstone or Lidam dolomite sequence may directly overlie

the Nubian, in which Timing

and migration.—In

the southern part of the Ajdabiya trough, the peak Traps.—Trap types for Nubian reservoirs are horsts, tilted fault blocks, updip unconformity truncations, and updip terminations against basement or Cambrian-Ordovician quartzite (Figure 9). Sabil traps are usually drape anticlines over buildups with lateral permeability barriers.

Reservoirs.—The

lower and upper sandstone members of the Nubian Formation are the

primary reservoir targets for the area. The maximum Nubian net sand

thickness in the graben is approximately 1000 ft (Figure

6). The Nubian

may be absent on Cambrian-Ordovician highs, similar to the setting in

the southeast Sirt Secondary reservoir objectives are few and high risk in the area because of limited distribution and poor development. The exceptions are reef and shoal carbonates of the Zaltan Formation and the Bahi sandstone. Zaltan Formation facies, consistent with the equivalent upper Sabil carbonate to the east, were not controlled by earlier faulting. A shelf margin extended across the southern part of the Maradah graben. Net thickness of the Zaltan in this area ranges from 0 in the north to more than 400 ft in the south. Depth to the top Zaltan is 7500 to 9000 ft. Because of this shallow depth, the Zaltan has been subjected to considerably more exploration than the Nubian.The basal Upper Cretaceous Bahi sandstone may attain thicknesses exceeding 600 ft in the graben. However, in places, part or all of the so-called Bahi sandstone may be Lower Cretaceous Nubian sandstone. Seals.—Etel shale and anhydrite at the Sirt unconformity provide an effective seal for the Nubian sandstone throughout most of the area. In a few places, the Nubian may lack an effective seal because the Bahi sandstone or Lidam dolomite directly overlies it. The Etel shale-evaporite sequence is also an excellent seal for Bahi and Lidam reservoirs. The Paleocene Harash or Kheir shales provide the seals for the Zaltan carbonates. Timing

and migration.—In

the Maradah trough, the peak Traps.—Trap types for Nubian reservoirs are most likely horsts, tilted fault blocks, and faulted anticlines. Combination traps also may be present, involving Nubian sandstone truncated at the Sirt unconformity or updip onlap of Nubian sandstone on the Cambrian-Ordovician surface. Trap types for the Bahi and Lidam Formations include horsts, tilted fault blocks, drape and faulted anticlines, and pinch-outs. Expected traps for Zaltan reservoirs are reef and shoal buildups, usually in combination with drape and faulted anticlines.

Southern Zallah Trough–Tumayam Trough Reservoirs.—The lower and upper sandstone members of the Nubian Formation and the Bahi sandstone are among the primary objectives (Schroter, 1996). In this area, it is difficult to differentiate between these two formations. Therefore, the thicknesses reported here are estimates. Nubian net sand thicknesses are estimated to range from 0 (at onlap and truncation limits) to approximately 1000 ft. The Bahi sandstone is expected to be from 0 to 300 ft thick. Depth to the top Nubian and Bahi ranges from 9500 to 14,000 ft. It is expected that average porosity will be 12–14% in both formations. Probably equally important reservoir targets are the Paleocene Defa and Beda Formations and the lower Eocene Facha high-energy carbonate facies. Barrier shoal carbonates are well developed in the Thalith, lower Beda, and upper Beda members of the Beda Formation in the northeast sector of the subject area (Bezan et al, 1996; Johnson and Nicoud, 1996; Sinha and Mriheel, 1996). Porosity in the lower and upper Beda members (Farrud sequence) ranges as high as 35%. Thickness of the Beda Formation exceeds 1000 ft, with as much as 600 ft of net porous carbonate (Figure 10). The Defa carbonate and Facha dolomite attain a net thickness of as much as 400 ft in the area. Approximately 25 wildcat wells have reached these formations in the area at depths of less than 9000 ft. However, the well density of 1 well/1000 km 2 indicates that the area is still underexplored, even at shallow levels. A secondary objective that has not been pursued is a Turonian-Senonian sandstone sequence, equivalent to the Rachmat and Sirt Formations, which is developed in the southern sector of the Tumayam trough. These porous sandstone beds thicken rapidly southward from their pinch-out limits to more than 1000 net ft (Figure 11). Seals.—Etel shale and anhydrite provide an effective seal for the Nubian and Bahi sandstones throughout most of the area. Locally, there is a slight risk that a thin Lidam dolomite sequence overlying the Nubian or Bahi would have prevented sealing. Hagfa and Khalifa shales are effective seals for Defa and Beda carbonates, and the Gir evaporites are reliable seals for the Facha dolomite. Interbedded shales should provide adequate seals for the individual Rachmat-Sirt sandstones. Timing

and migration.—In

the central part of the South Zallah– Tumayan trough area, where the

top of the Sirt shale is between 9000 and 11,000 ft, the main stage of

Secondary

migration from Sirt shale to underlying Nubian and Bahi reservoirs, as

is the Traps.—Trap types for Nubian reservoirs are expected to be the same here as in the Maradah and Ajdabiya troughs. Trap types for Bahi sandstone should include tilted fault blocks, drape and faulted anticlines, and pinch-outs. Northerly oriented pinch-outs of the Turonian-Senonian sandstones, in combination with dip or fault closures, are expected in the southern sector of the area. Reef and shoal buildups, in combination with anticlinal drape or faults, are the most likely traps for Defa and Beda reservoirs.

General.—The

Ghadamis During

that same period, there was minimal success in the Libyan sector,

although geologic setting and reservoirs are essentially the same. In

the study area, 27 wildcats yielded one Reservoirs.—The main reservoir targets for the area are the Upper Silurian Acacus Formation and the Lower Devonian Tadrart and Kasa Formations (Figure 15) (Said, 1974; Masera Corporation, 1992; Echikh, 1998). The Acacus net sandstone thickness ranges from approximately 500 to 1300 ft (Figure 16). The Acacus average porosity is at least 16%. The Tadrart and Kasa Formations should have a net sandstone thickness of 300–700 ft and an average porosity of 14–15% in the study area. These formations, which are a more or less continuous stratigraphic succession, are at depths between 8000 and 12,500 ft (Figure 17). Only eight exploration wells, most of which were in the north, reached these objectives in the study area. Three other sandstone reservoirs are valid objectives, but because of their shallower depths, they have been the subject of more exploratory drilling than the above formations. They are the Middle Devonian Uennin sandstone (equivalent of the F3 in Algeria), with a thickness range of 0 to 300 ft; the Upper Devonian Tahara Formation, with a net sand range of 50 to 200 ft; and the Triassic Ras Hamia Formation, with a net sandstone thickness of 200 to 700 ft. All of these sandstones have very good porosity, averaging 14–18%. Seals.—Generally, there is an effective Acacus shale seal above the sandstone. Where it may be absent, however, the overlying Tadrart will form a combined objective with the Acacus sandstone. Shale horizons consistently provide adequate seals for Tadrart, Kasa, F3 equivalent, and Tahara sandstones. Throughout most of the area, there are effective shale, carbonate, or evaporite seals for the Ras Hamia sandstone. Because of a dominant continental siliciclastic facies above the Ras Hamia in the southern part of the area, however, a seal may be lacking. Source

rock, timing, and migration.—There

are two world-class, type II source rocks distributed throughout the

entire The

peak In

this central Conditions for migration were optimum, in view of the short distance and vertical and lateral carrier systems from the two sources to the multiple reservoirs. Traps.—The expected trap types are low-relief, simple, and faulted anticlines; drape anticlines over paleotopographic relief or faulted structures; unconformity truncation of the Tahara sand in the northern part of the study area; and pinch-outs of the Uennin F3 equivalent sand.

General.—This

underexplored The

Murzuq Reservoirs.—Main

potential reservoirs for the area include the Acacus and the Lower

Devonian Tadrart-Kasa sandstones, as well as the main pay in the The Acacus net sandstone thickness is from 0 (at the north edge of the study area, where it is truncated) to 300 ft. The average porosity of the Acacus sandstone is approximately 15%. The Tadrart-Kasa sandstones, undifferentiated, have an estimated net thickness of as much as 200 ft and an average porosity similar to that of the Acacus. This sequence pinches out at the Caledonian surface in the northern part of the area. The

depth to the Memouniat ranges from 8000 to 11,500 ft. The Acacus and

Tadrart-Kasa are at depths of 6500 to 10,500 ft in the Murzuq Seals.—The

Tanezzuft shale provides a reliable seal throughout the area for the

Memouniat Formation. Generally, effective shale seals are interbedded

with Acacus sandstone beds. In a few places, upper Acacus sandstones are

overlain by Tadrart-Kasa sandstones, which could create a combined

reservoir, as in the Ghadamis Source

rock, timing, and migration.—The

Tanezzuft shale is the only effective Vertical,

updip, and fault pathways provided easy, short-distance pathways for

migration of Traps.—Structural

trap types are basically the same as those in the

Ghadamis

General.—The

offshore Tripolitania Reservoirs.—Based

on regional projections, numerous potential reservoir suites are in this

Cretaceous

reservoir considerations are speculative. However, based on

stratigraphic projection from a few wells in the western part of the

Tripolitania Seals.—Shale

and argillaceous limestone (mudstone-wackestone) beds provide effective

seals for the underlying Cretaceous and Eocene reservoirs throughout

most of the eastern sector of the Source,

timing, and migration.—Mature

organic-rich type II source beds have been identified in four formations

in the Along

the extreme southwest part of the study area, the Silurian Tanezzuft

shale thickens from an erosional edge on the north to more than 1000 ft

at the southwest limits of the study area (Belhaj, 1996). It is

estimated that Tanezzuft TOC is between 1% and 8%, based on Ghadamis

The

peak Traps.—The trap types expected in the study area include faulted anticlines, horsts and tilted fault blocks, drape anticlines over carbonate buildups or faulted relief, and updip lithology or permeability pinch-outs.

The

six underexplored In

the Sirt In the Ghadamis and Murzuq Basins, sandstone sequences of the Upper Silurian Acacus and Lower Devonian Tadrart-Kasa Formations are definitely quality objectives, but they have not been priority targets. In the Ghadamis study area, which covers 20,000 km 2 , only eight exploration wells reached the Acacus. In

the eastern Tripolitania The critical factor in determining future exploration success in the underexplored depocenters will probably be accurate trap definition. In general, at this stage in the exploration history of Libya, it is expected that the majority of the focus will be on subtle and complex trap types: low-relief faulted structures and drape anticlines, structural-stratigraphic combination traps involving facies pinch-outs, onlap terminations, and unconformity truncation. Identifying specific traps is complicated further by the fact that they are at considerable depths. Therefore,

it will be necessary to adopt an integrated, interdisciplinary approach

for in-depth, accurate interpretation of the specific trap or prospect.

To accomplish this optimum level of trap definition, a detailed geologic

database and state-of-the-art tools and methods will be required,

including, for example, 3-D seismic, sequence stratigraphy, and

I extend special thanks to Paul McDaniel and John W. Shelton of Masera Corporation for their welcome assistance in the preparation of this paper and for the use of the Masera data set on Libya.

Abdulghader,

G. S., 1996, Depositional environment and diagenetic history of the

Maragh formation, NE Sirt Anketell,

J. M., 1996, Structural history of the Sirt Baird,

D. W., R. M. Aburawi, and N. J. L. Bailey, 1996, Geohistory and

petroleum in the central Sirt Bailey, H. W., G. Dungworth, M. Hardy, D. Scull, and R. D. Vaughan, 1989,A fresh approach to the Metlaoui: Actes de IIeme Journees de Géologie Tunisienne Appliquée à la Recherche des Hydrocarbures: Memoire de Enterprise Tunisienne d’Activités Petrólières 3, p. 281–308. Baric,

G., D. Spanic, and M. Maricic, 1996, Geochemical characterization of

source rocks in NC 157 block (Zaltan platform), Sirt Barr,

F. T., and A. A. Weegar, 1972, Stratigraphic nomenclature of the Sirte

Belhaj,

F., 1996, Paleozoic and Mesozoic stratigraphy of eastern Ghadamis and

western Sirt Basins, in

M. J.

Salem, A. S. El-Hawat, and A. M. Sbeta, eds., Geology of the Sirt Bellini, E., and D. Massa, 1980, A stratigraphic contribution to the Palaeozoic of the southern basins of Libya, in M. J. Salem and M. T. Busrewil, eds., Geology of Libya: London, Academic Press, p. 3–56. Bernasconi, A., G. Poliani, and A. Dakshe, 1991, Sedimentology, petrography and diagenesis of Metlaoui Group in the offshore northwest of Tripoli, in M. J. Salem and M. N. Belaid, eds., The Geology of Libya: Third Symposium on the Geology of Libya, held at Tripoli, September 27–30, 1987: Amsterdam, Elsevier, v. 5, p. 1907–1928. Bezan,

A. M., F. Belhaj, and K. Hammuda, 1996, The Beda formation of the Sirt

Bishop, W. F., 1988, Petroleum geology of east-central Tunisia: AAPG Bulletin, v. 72, p. 1033–1058. Bonnefous,

J., 1972, Geology of the quartzitic “Gargaf Formation” in the Sirte

Boote, D. R. D., D. D. Clark-Lowes, and M. W. Traut, 1998, Palaeozoic petroleum systems of North Africa, in D. S. MacGregor, R. J. T. Moody, and D. D. Clark-Lowes, eds., Petroleum geology of North Africa: Geological Society of London, p. 7–68. Caron, M., F. Robaszynski, F. Amedro, F. Baudin, J.-F. Deconinck, P. Hochuli, K. von Salis-Perch Nielsen, and N. Tribovillard, 1999, Estimation de la durée de l’événement anoxique global au passage Cenomanien/Turonien: Approche cyclostratigraphique dans la formation Bahloul en Tunisie centrale: Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France, v. 170, p. 145–160. Clifford,

H. J., R. Grund, and H. Musrati, 1980, Geology of a stratigraphic giant:

Messla Echikh,

K., 1998, Geology and hydrocarbon occurrences in the Ghadames El-Alami,

M.A., 1996a, Petrography and reservoir quality of the Lower Cretaceous

sandstone in the deep Maragh trough,

Sirt El-Alami,

M. A., 1996b, Habitat of El-Ghoul,

A., 1991, A modified Farwah Group type section and its application to

understanding stratigraphy and sedimentation along an E-W section

through NC35A, Sabratah El-Hawat,

A. S., A. A. Missallati, A. M. Bezan, and T. M. Taleb, 1996, The Nubian

sandstone in Sirt Ghori,

K. A. R., and R. A. Mohammed, 1996, The application of petroleum

generation modelling to the eastern Sirt Gras,

R., 1996, Structural style of the southern margin of the Messlah High, in

M. J.

Salem, A. S. El-Hawat, and A. M. Sbeta, eds., Geology of the Sirt Gumati,

Y. D., and W. H. Kanes, 1985, Early Tertiary subsidence and sedimentary

facies—northern Sirte Gumati,

Y. D., and A. E. M. Nairn, 1991, Tectonic subsidence of the Sirte Gumati,

Y. D., and S. Schamel, 1988, Thermal maturation history of the Sirte

Hallett,

D., and A. El-Ghoul, 1996, Hamyouni,

E. A., 1991, Petroleum source rock evaluation and timing of hydrocarbon

generation, Murzuk Hamyouni,

E. A., I. A.Amr, M. A. Riani, A. B. El-Ghull, and S. A. Rahoma, 1984,

Source and habitat of Ibrahim,

M. W., 1991, Petroleum geology of the Sirt Group sandstones, eastern

Sirt Johnson,

B. A., and D. A. Nicoud, 1996, Integrated exploration for Beda Formation

reservoirs in the southern Zallah trough (West Sirt Klitzsch, E., 1971, The structural development of parts of North Africa since Cambrian time, in C. Gray, ed., Symposium on the geology of Libya: Tripoli, Faculty of Science of the University of Libya, p. 253–262. Koscec,

B. G., and Y. S. Gherryo, 1996, Geology and reservoir performance of

Messlah Loucks, R. G., R. T. J. Moody, J. K. Bellis, and A. A. Brown, 1998, Regional depositional setting and pore network systems of the El Garia Formation (Metlaoui group) lower Eocene, offshore Tunisia, in D. S. MacGregor, R. J. T. Moody, and D. D. Clark-Lowes, eds., Petroleum geology of North Africa: Geological Society of London, p. 355–374. Mansour,

A. T., and I. A. Magairhy, 1996, Petroleum geology and stratigraphy of

the southeastern part of the Sirt Masera Corporation, 1992, Exploration geology and geophysics of Libya: Tulsa, Oklahoma, Masera Corporation, 205 p. Meister,

E. M., E. F. Ortiz, E. S. T. Pierobon, A. A. Arruda, and M. A. M.

Oliveira, 1991, The origin and migration fairways of petroleum in the

Murzuq Parsons,

M. G., A. M. Zagaar, and J. J. Curry, 1980, Hydrocarbon occurrence in

the Sirte Roohi,

M., 1996a, A geological view of source-reservoir relationships in the

western Sirt Roohi,

M., 1996b, Geological history and hydrocarbon migration pattern of the

central Az Zahrah–Al Hufrah platform, in

M. J.

Salem, A. S. El-Hawat, and A. M. Sbeta, eds., Geology of the Sirt Said,

F. M., 1974, Sedimentary history of the Paleozoic rocks of the Ghadames

Sbeta, A. M., 1990, Stratigraphy and lithofacies of Farwah Group and its equivalent: offshore—NW Libya: Petroleum Research Journal, v. 2, p. 42–56. Schroter,

T., 1996, Tectonic and sedimentary development of the central Zallah

trough (West Sirt Sinha,

R. N., and I. Y. Mriheel, 1996, Evolution of subsurface Palaeocene

sequence and shoal carbonates, south-central Sirt Spring,

D., and O. P. Hansen, 1998, The influence of platform morphology and sea

level on the development of a carbonate sequence: The Harash Formation,

eastern Sirt Van Houten, B. F., 1980, Latest Jurassic–earliest Cretaceous regressive facies, northeast African craton: AAPG Bulletin, v. 64, p. 857–867. |

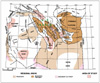

Figure

1. Generalized tectonic map of Libya showing major structural features.

Also shown are six underexplored central

Figure

1. Generalized tectonic map of Libya showing major structural features.

Also shown are six underexplored central  Figure

14. (a) North-south structural cross section A-A’, Ghadamis

Figure

14. (a) North-south structural cross section A-A’, Ghadamis