![]() Click to view article in PDF format.

Click to view article in PDF format.

Three-Dimensional  Prestack

Prestack Inversion, Lobo Trend,

South Texas*

Inversion, Lobo Trend,

South Texas*

By

Phil Anno1, Mark Wuenscher1, Robert Corbin1, John Hooper1, and Frank Chlumsky2

Search and Discovery Article #10039 (2003)

*Adapted from “extended abstract” of presentation at AAPG Annual Meeting, March 10-12, 2002, Houston, Texas.

1Conoco Inc., Ponca City, Oklahoma

2Conoco Inc., Houston, Texas

We demonstrate the difficulty with mapping a Lobo (Paleocene) hydrocarbon reservoir directly from stacked seismic data. A strong response in the stacked volume is ambiguous, indicating either a large impedance contrast or a contrast in Poisson’s ratio.

That is, stacking of reflection amplitudes over offset (or reflection angle) incorporates reflections from impedance perturbations with those due to a change in Poisson’s ratio. Dipole sonic log data indicate Poisson’s ratio, but not impedance, distinguishes this particular Lobo reservoir from shale. The hydrocarbon reservoir impedance is similar to that of encasing shales. On the other hand, Poisson’s ratio decreases over 30% in the reservoir sand.

In this paper, we

invert the  prestack

prestack amplitudes of a 3-D data volume to distinguish perturbations

in impedance from Poisson’s ratio perturbations. We may, therefore, recognize

and map this Lobo reservoir as a decrease in Poisson’s ratio accompanied by

little or no change in impedance.

amplitudes of a 3-D data volume to distinguish perturbations

in impedance from Poisson’s ratio perturbations. We may, therefore, recognize

and map this Lobo reservoir as a decrease in Poisson’s ratio accompanied by

little or no change in impedance.

|

|

Click here to view sequence of Figures 1 and 2 (P-wave impedance and Poisson’s Ratio logs).

The upper Paleocene to Eocene Wilcox Lobo trend is a major low-permeability natural gas producer of the Texas Gulf Coast, already yielding approximately 4.5 TCF of gas. Both structural and stratigraphic complexity can complicate exploration and exploitation of the Lobo trend. Multiple episodes of faulting and erosion can make sand correlation difficult from fault block to fault block. Previous Lobo exploration tools consisted of open-hole logs and dipmeter data combined with 2-D seismic data. These techniques were useful for exploring large slump block features. Over time, the success of these techniques diminished as the size of potential targets decreased. Continuous improvements in 3-D acquisition and processing over the last ten years have positively impacted Lobo exploration and development success. Current 3-D stack volumes resolve much smaller slump blocks. This improved structural definition helps identify acreage that yields superior drilling results. Modern

dipole sonic log measurements through the Lobo section point to

Poisson’s ratio as a distinguishing reservoir property. In this paper we directly image a Lobo reservoir by inverting amplitudes before stack. A signature decrease in Poisson’s ratio tracks the reservoir across faulting.

The well

data of Figures 1 and

2 make the case for

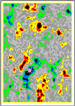

One can invert throughout the 3-D volume for perturbations in Poisson’s ratio, along with impedance perturbations. This inversion requires reflection amplitudes from different angles, incident on the same image point in the volume. Figures 3 and 4 give time slices of the resulting inversion output. These pictures show, respectively, an image of the perturbations in impedance and Poisson’s ratio. The Lobo reservoir at 9650 ft, for example, exhibits a large drop in Poisson’s ratio but no impedance signature. See Figure 5 for a color bar. Though this

R(q ) =A + Bsin2q + Csin2q tan2q + K (1) Equation (1) expresses reflectivity R as a function of incidence angleq. One derives this equation following the approaches taken by Bortfeld (1961), and Aki and Richards (1980). Shuey (1985) presented a similar approximation. Equation

(1) also sets the goal of our entire Parameter A in equation (1) equates to a perturbation in impedance under the assumption of small perturbations. Parameter B is the source of information on Poisson’s ratio. It depends in part on the product of perturbations in both impedance and Poisson’s ratio. We

truncated equation (1) before parameter C for the inversion of

Figures 3 and 4. One often neglects this third term for incidence angles

less than 25o, the

maximum angle preserved through our

Equation (1) thus makes it clear that stacking of reflection amplitudes over angle incorporates reflections from impedance perturbations with those due to a change in Poisson’s ratio. The A -term contributes the former, the B -term the latter. A strong response in the stacked volume is therefore ambiguous in terms of rock properties. Figures 6, 7 and 8 taken together document this ambiguity for the Lobo section. The band of prominent reflections in the stack data, just above 1.8 s, originates mainly from impedance perturbations. The event marked by an arrow in these figures is an exception. Inversion before stack attributes this event to low Poisson’s ratio (Figure 6). This signature gives a direct image of the reservoir, mappable away from well control and across fault terminations. On the other hand, this Lobo hydrocarbon reservoir is virtually transparent by way of impedance (Figure 8).

Multiple episodes of faulting and erosion in the Lobo trend can frustrate seismic correlation and mapping. Moreover, these Lobo reservoirs often produce a faint expression in the stack volume, especially compared to reflections from large impedance contrasts. Dipole

sonic log data reveal the petrophysical key to this problem. These Lobo

reservoirs are reflective at non-zero incidence angles via a decrease in

Poisson’s ratio. We may, therefore, directly image and map the reservoir

by inverting

We thank

Peter Lellis for hisencouragement and initiative to apply

Aki, K., and Richards, P.G., 1980, Quantitative seismology: Theory and methods: W.H. Freeman and Co. Bortfeld, R., 1961, Approximation to the reflection and transmission coefficients of plane longitudinal and transverse waves: Geophys. Prosp., v. 9, 485-503. Shuey, R.T., 1985, A simplification of the Zoeppritz equations: Geophysics, v. 50, p. 609-614.

|

Figure 1.

P-wave impedance well log, coded according to log-derived lithology. The

legend provides the code.

Figure 1.

P-wave impedance well log, coded according to log-derived lithology. The

legend provides the code. Figure 2.

Poisson’s Ratio well log, coded according to log-derived lithology.

Figure 2.

Poisson’s Ratio well log, coded according to log-derived lithology. Figure 3. A

time slice through the impedance perturbation cube from 3-D

Figure 3. A

time slice through the impedance perturbation cube from 3-D  Figure 4. A

time slice through the Poisson’s Ratio perturbation cube from 3-D

Figure 4. A

time slice through the Poisson’s Ratio perturbation cube from 3-D

Figure 6.

An inline slice through the Poisson’s Ratio perturbation cube from 3-D

Figure 6.

An inline slice through the Poisson’s Ratio perturbation cube from 3-D

Figure 7.

An inline slice through the amplitude stack cube.

Figure 7.

An inline slice through the amplitude stack cube. Figure 8.

An inline slice through the impedance perturbation cube from

Figure 8.

An inline slice through the impedance perturbation cube from