GCSpectral Balancing Aids Seeing Faults More Clearly*

Satinder Chopra¹ and Kurt J. Marfurt²

Search and Discovery Article #41594 (2015)

Posted March 20, 2015

*Adapted from the Geophysical Corner column, prepared by the authors, in AAPG Explorer, March, 2015, and entitled "A Delicate Balance: Seeing Faults More Clearly". Editor of Geophysical Corner is Satinder Chopra ([email protected]). Managing Editor of AAPG Explorer is Vern Stefanic. AAPG © 2015

¹Arcis  Seismic

Seismic Solutions, TGS, Calgary, Canada ([email protected])

Solutions, TGS, Calgary, Canada ([email protected])

²University of Oklahoma, Norman, Oklahoma

Spectral decomposition of  seismic

seismic data helps in the analysis of subtle stratigraphic plays and fractured reservoirs. The different methods used for decomposing the

data helps in the analysis of subtle stratigraphic plays and fractured reservoirs. The different methods used for decomposing the  seismic

seismic data into individual frequency components within the

data into individual frequency components within the  seismic

seismic data bandwidth serve to transform the

data bandwidth serve to transform the  seismic

seismic data from the time domain to the frequency domain – and generate the spectral magnitude and

data from the time domain to the frequency domain – and generate the spectral magnitude and  phase

phase components at every time-frequency sample.

components at every time-frequency sample.

The spectral amplitude and  phase

phase components are analyzed at different frequencies, which means essentially interpreting the subsurface stratigraphic features at different scales. More recently, another important attribute that could be generated during spectral decomposition has been introduced, and is referred to as the voice component at every time-frequency component. For more details of this attribute, see Geophysical Corner article Autotracking Horizons in

components are analyzed at different frequencies, which means essentially interpreting the subsurface stratigraphic features at different scales. More recently, another important attribute that could be generated during spectral decomposition has been introduced, and is referred to as the voice component at every time-frequency component. For more details of this attribute, see Geophysical Corner article Autotracking Horizons in  Seismic

Seismic Records – Search & Discovery Article #41489.

Records – Search & Discovery Article #41489.

The voice component at any individual frequency, say 30 Hz, is obtained by cross-correlating the  seismic

seismic amplitude data with the mother wavelet (such as the Morlet wavelet), centered at 30 Hz with a frequency width of 30 Hz on either side. Thus the bandwidth of the voice component increases as the frequencies increase from the lower end to the higher end of the bandwidth. One may consider the process to be equivalent to applying a narrow band pass filter centered at 30 Hz to the data, but having some narrow bandwidth around on both sides.

amplitude data with the mother wavelet (such as the Morlet wavelet), centered at 30 Hz with a frequency width of 30 Hz on either side. Thus the bandwidth of the voice component increases as the frequencies increase from the lower end to the higher end of the bandwidth. One may consider the process to be equivalent to applying a narrow band pass filter centered at 30 Hz to the data, but having some narrow bandwidth around on both sides.

|

♦General statement ♦Figures ♦Examples ♦Method ♦Conclusions

♦General statement ♦Figures ♦Examples ♦Method ♦Conclusions

♦General statement ♦Figures ♦Examples ♦Method ♦Conclusions

♦General statement ♦Figures ♦Examples ♦Method ♦Conclusions |

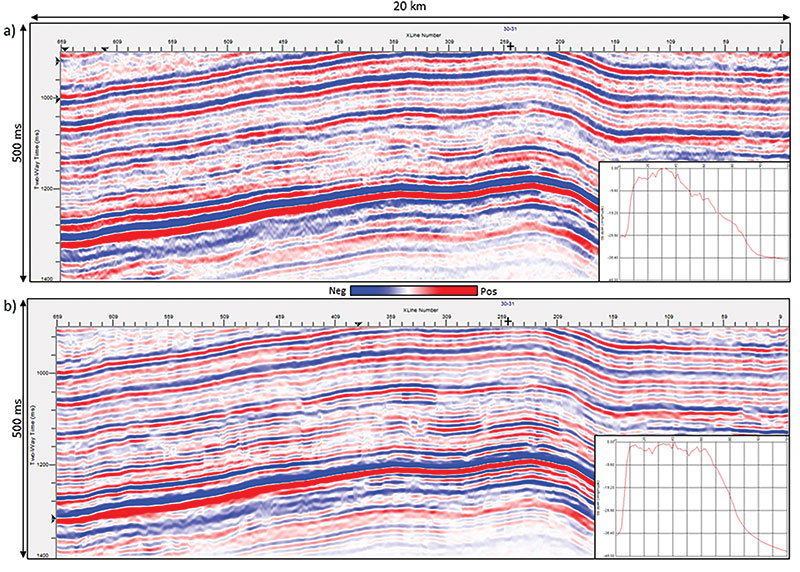

We show an example of a voice component section in Figure 1, along with its amplitude spectrum. Such voice components offer more information that could be processed and interpreted. We have focused on interpretational objectives of spectral decomposition in our earlier articles in the Geophysical Corner (Spectral Decomposition's Analytical Value – Search & Discovery Article #41260, and Extracting Information from Texture Attributes – Search & Discovery Article #41330) and demonstrated our examples pertaining to channels and other stratigraphic features. In this article our examples focus on faults and fractures. In Figure 2 we show a segment of a Traditionally, the spectral component magnitudes at different dominant frequencies have been utilized for obtaining detailed perspectives on stratigraphic objectives. As an example, the thickness of a channel is correlated with the spectral magnitude. More detailed information on In another Geophysical Corner article (Spectral Balancing Can Enhance Vertical Resolution – Search & Discovery Article #41357), Marfurt and Matos described an amplitude-friendly method for spectrally balancing the Next, the peak of the average power spectrum also is computed. Both the average spectral magnitude and the peak of the average power spectrum are used to design a single time-varying spectral balancing operator that is applied to each and every trace in the data. As a single scalar is applied to the data, the process is considered as being amplitude friendly. Figure 3 shows segments of a Encouraged with the higher frequency content of the data, we run Energy Ratio coherence on the input data as well as the spectrally balanced version of the data. The results are shown in Figures 4a, b and 5a, b, where we notice the better definition of the NNW-SSE faults as well as the faults/fractures in the E-W direction on the coherence run on spectrally balanced version. Finally, we run the spectral decomposition on spectrally balanced version of the input The conclusions that one can draw from the foregoing examples is that spectral balancing of |