![]() Click to view page images in PDF format.

Click to view page images in PDF format.

Tectonostratigraphic Framework of the Columbus Basin, Eastern Offshore Trinidad*

L. J. Wood

Article #10014 (2001)

*Adapted for online presentation from article, entitled “Chronostratigraphy and Tectonostratigraphy of the Columbus Basin, Eastern Offshore Trinidad," by the author in AAPG Bulletin, v. 84, no. 12 (December, 2000), p. 1905-1928.

1Bureau of Economic Geology, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas 78713-8924; email: [email protected]

The Columbus Basin, forming the easternmost part of the Eastern Venezuela Basin, is situated along the obliquely converging margins of the Caribbean and South American plates. The two primary structural elements that characterize the basin are (1) transpressional northeast-southwest-trending anticlines and (2) northwest-southeast-oriented, down-to-the-northeast, extension normal faults. The basin was filled throughout the Pliocene and Pleistocene by more than 40,000 ft (>12,200 m) of clastic sediment supplied primarily by the Paleo-Orinoco Delta system. The delta prograded eastward over a storm-influenced and current-influenced shelf during the Pliocene-Pleistocene, depositing marine and terrestrial clastic megasequences as a series of prograding wedges atop a lower Pliocene to pre-Pliocene mobile shale facies.

Biostratigraphic and well log data from 41 wells were integrated with

thousands of kilometers of interpreted two-dimensional and three-dimensional

seismic data to construct a chronostratigraphic framework for the basin. As a

result, several observations were made regarding the basin's geology that have a

bearing on exploration risk and success: (1) megasequences wedge bidirectionally;

(2) consideration of  hydrocarbon

hydrocarbon -system risk across any area requires looking at

these sequences as complete paleofeatures; (3) reservoir location is influenced

by structural elements in the basin; (4) the lower limit of a good-quality

reservoir in any megasequence deepens the closer it comes to the normal fault

bounding the wedge in a proximal location; (5) reservoir quality of deep-marine

strata is strongly influenced by both the type of shelf system developed (bypass

or aggradational) and the location of both subaerial and submarine highs; and

(6) submarine surfaces of erosion partition the megasequences and influence

hydrostatic pressure, migration, and trapping of hydrocarbons and the

distribution of

-system risk across any area requires looking at

these sequences as complete paleofeatures; (3) reservoir location is influenced

by structural elements in the basin; (4) the lower limit of a good-quality

reservoir in any megasequence deepens the closer it comes to the normal fault

bounding the wedge in a proximal location; (5) reservoir quality of deep-marine

strata is strongly influenced by both the type of shelf system developed (bypass

or aggradational) and the location of both subaerial and submarine highs; and

(6) submarine surfaces of erosion partition the megasequences and influence

hydrostatic pressure, migration, and trapping of hydrocarbons and the

distribution of  hydrocarbon

hydrocarbon type.

type.

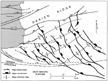

Figure

1. Tectonic map (after Pocknall et al., 1999) showing regional structural

features of northern South America, including the island of Trinidad, as well as

the modern outlet of the Orinoco River and location of the present-day delta

relative to the Columbus Basin. Soldado 189 well is indicated in the Gulf of

Paria.

Figure

1. Tectonic map (after Pocknall et al., 1999) showing regional structural

features of northern South America, including the island of Trinidad, as well as

the modern outlet of the Orinoco River and location of the present-day delta

relative to the Columbus Basin. Soldado 189 well is indicated in the Gulf of

Paria.

Figure

2. Major structural features of the Columbus Basin, offshore eastern

Trinidad, including regional normal faults, right lateral strike-slip faults,

and offshore structural ridge trends.

Figure

2. Major structural features of the Columbus Basin, offshore eastern

Trinidad, including regional normal faults, right lateral strike-slip faults,

and offshore structural ridge trends.

Click here for sequence and overlay of Figures 2 and 4.

Figure

3. Simplified stratigraphic chart of the Eastern Venezuela Basin (after

Heppard et al., 1998). Major source rock intervals have been identified as the

Upper Cretaceous San Antonio and Querecual formations in eastern Venezuela and

the Naparima Hill and Gautier formations in Trinidad. Units that have been

important reservoirs are also indicated. The dotted line indicates the

diachronous nature of top overpressure as it climbs stratigraphically to the

Figure

3. Simplified stratigraphic chart of the Eastern Venezuela Basin (after

Heppard et al., 1998). Major source rock intervals have been identified as the

Upper Cretaceous San Antonio and Querecual formations in eastern Venezuela and

the Naparima Hill and Gautier formations in Trinidad. Units that have been

important reservoirs are also indicated. The dotted line indicates the

diachronous nature of top overpressure as it climbs stratigraphically to the

east

east .

.

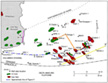

Figure

4. Columbus Basin and the island of Trinidad showing wells used in this

study and location of major oil and gas fields. Cross section AA' and seismic

line XX' are shown in Figures 7 and 5,

respectively. Outcrop photographs are

shown in Figures 9a and 9b.

Figure

4. Columbus Basin and the island of Trinidad showing wells used in this

study and location of major oil and gas fields. Cross section AA' and seismic

line XX' are shown in Figures 7 and 5,

respectively. Outcrop photographs are

shown in Figures 9a and 9b.

Click here for sequence and overlay of Figures 2 and 4.

Figure

5. (a) Southwest-northeast-trending seismic line XX' (see Figure 4

for

location) and (b) accompanying line drawing illustrating the two-dimensional

geometry of normal fault and counterregional glide surface and their

relationship to one another. Regionally extensive lowstand surfaces

(unconformities) and their basinward-equivalent correlative conformities that

bound megasequences are shown. Note the thickening of sediments down into the

counterregional surface and the upturned toe reflectors associated with sediment

drag as shale evacuates from beneath the sediment wedge (SP1800-1600 between 3.0

and 5.0 s). Sediment wedges thin landward (southwest) and show truncation of

their upper parts by means of the lowstand surface of the overlying sequence.

Significant thickening of sediments occurs across major normal faults (SP2100,

SP2740). Although similar seismic facies are identifiable in different fault

blocks at approximately the same seismic depth, they are of different ages, as

shown by biostratigraphic data (see Figure 10).

Figure

5. (a) Southwest-northeast-trending seismic line XX' (see Figure 4

for

location) and (b) accompanying line drawing illustrating the two-dimensional

geometry of normal fault and counterregional glide surface and their

relationship to one another. Regionally extensive lowstand surfaces

(unconformities) and their basinward-equivalent correlative conformities that

bound megasequences are shown. Note the thickening of sediments down into the

counterregional surface and the upturned toe reflectors associated with sediment

drag as shale evacuates from beneath the sediment wedge (SP1800-1600 between 3.0

and 5.0 s). Sediment wedges thin landward (southwest) and show truncation of

their upper parts by means of the lowstand surface of the overlying sequence.

Significant thickening of sediments occurs across major normal faults (SP2100,

SP2740). Although similar seismic facies are identifiable in different fault

blocks at approximately the same seismic depth, they are of different ages, as

shown by biostratigraphic data (see Figure 10).

Click here for sequence and overlay of seismic line and line drawing.

Figure

6. Paleogeography of the lowstand paleo-Orinoco Delta in the Pliocene and

Pleistocene. Low-sloping broad fluvial distributary plain feeds line-source,

wave-modified strand-plain shoreline systems. These systems in turn feed

line-sourced slope and fan deposits. Rising shale diapirs at the toe of the

slope helped focus slope and basin floor deposition and ponded thick sediments

on the basin floor in toe-of-slope sediment sinks.

Figure

6. Paleogeography of the lowstand paleo-Orinoco Delta in the Pliocene and

Pleistocene. Low-sloping broad fluvial distributary plain feeds line-source,

wave-modified strand-plain shoreline systems. These systems in turn feed

line-sourced slope and fan deposits. Rising shale diapirs at the toe of the

slope helped focus slope and basin floor deposition and ponded thick sediments

on the basin floor in toe-of-slope sediment sinks.

Figure

7. Southwest-northeast well log cross section AA' from Poui field to

Figure

7. Southwest-northeast well log cross section AA' from Poui field to  East

East Mayaro field across the Columbus Basin, illustrating the typical gamma-log

(left) and resistivity-log (right) signatures associated with depositional

facies that make up the prograding megasequences. Note the abrupt stratigraphic

thickening across the major normal growth faults in the depositional dip

direction (OPR4-Omega and Flambouyant-NEQB-EM3-EM1), as well as the continuity

of facies in the depositional strike direction (Omega-Flambouyant). Logs and

base Pleistocene pick in OPR4 and Flambouyant are from Heppard et al. (1998).

Environments of deposition are based on interpretation of integrated

biostratigraphic data, well log motifs, seismic facies, and regional

paleogeography. Line of section shown in Figure 4.

Mayaro field across the Columbus Basin, illustrating the typical gamma-log

(left) and resistivity-log (right) signatures associated with depositional

facies that make up the prograding megasequences. Note the abrupt stratigraphic

thickening across the major normal growth faults in the depositional dip

direction (OPR4-Omega and Flambouyant-NEQB-EM3-EM1), as well as the continuity

of facies in the depositional strike direction (Omega-Flambouyant). Logs and

base Pleistocene pick in OPR4 and Flambouyant are from Heppard et al. (1998).

Environments of deposition are based on interpretation of integrated

biostratigraphic data, well log motifs, seismic facies, and regional

paleogeography. Line of section shown in Figure 4.

Figure

8. Biostratigraphic ranges defined by Pocknall et al. (1999) and derived in

conjunction with this study to differentiate chronostratigraphy of the Columbus

Basin.

Figure

8. Biostratigraphic ranges defined by Pocknall et al. (1999) and derived in

conjunction with this study to differentiate chronostratigraphy of the Columbus

Basin.

Figure

9. Photographs of Pliocene shelf-deltaic deposits of Gros Morne Formation of

the Columbus Basin outcropping along the southeast coast of Trinidad show

soft-sediment deformation, including (a) large channel scour truncating

underlying fine-grained sandstone, siltstone, and claystones deposited in a

shelf deltaic setting. The channel scours into structurally tilted sediments.

Its irregular base is filled with large rectangular blocks, which were

semicohesive when deposited and are composed of the substrate material. The

remainder of the channel is filled with alternating wavy-bedded silty sands and

shales. (b) Flame structure, characteristic of these rapidly deposited

sediments. Location of photos shown in Figure 4.

Figure

9. Photographs of Pliocene shelf-deltaic deposits of Gros Morne Formation of

the Columbus Basin outcropping along the southeast coast of Trinidad show

soft-sediment deformation, including (a) large channel scour truncating

underlying fine-grained sandstone, siltstone, and claystones deposited in a

shelf deltaic setting. The channel scours into structurally tilted sediments.

Its irregular base is filled with large rectangular blocks, which were

semicohesive when deposited and are composed of the substrate material. The

remainder of the channel is filled with alternating wavy-bedded silty sands and

shales. (b) Flame structure, characteristic of these rapidly deposited

sediments. Location of photos shown in Figure 4.

Figure

10. Chronostratigraphic chart of the Columbus Basin, showing progradational

character of the basin fill throughout the Pliocene and Pleistocene. Regional

subsidence in the southwest parts of the basin resulted in continuous

aggradation of mixed fluvial and estuarine deposits over much of the area.

Unconformities exhibit the greatest amounts of missing time in locations central

to the structural hinge of each megasequence. Foraminiferal and palynological

ranges are from Pocknall et al. (1999).

Figure

10. Chronostratigraphic chart of the Columbus Basin, showing progradational

character of the basin fill throughout the Pliocene and Pleistocene. Regional

subsidence in the southwest parts of the basin resulted in continuous

aggradation of mixed fluvial and estuarine deposits over much of the area.

Unconformities exhibit the greatest amounts of missing time in locations central

to the structural hinge of each megasequence. Foraminiferal and palynological

ranges are from Pocknall et al. (1999).

Figure

11. Curves showing sea level change, fauna discontinuities, and sequence

boundaries for the world (columns 1, 2, 3) (Haq et al., 1988), the U.S.A.

margins of the Gulf of Mexico (columns 4, 5, 6), and the Columbus Basin,

Trinidad. Some sequence boundaries in the Columbus Basin appear correlative with

time-equivalent sea level falls and associated sequence boundaries identified in

other areas of the world. These sequence boundaries in the Columbus Basin are

most likely a function of eustatic base-level change (E); others appear to have

a more local tectonic origin (T). The tectonic nature of these boundaries is

supported by the presence in some wells of Cretaceous, Eocene, and Oligocene

fauna and flora identified as reworked in association with these boundaries (Pocknall

et al., 1999). Sources for the curves are (1) Beard et al. (1982); (2) Lamb et

al. (1987); (3) Haq et al. (1988); (4) Wornhardt and Vail (1990); (5) Pacht et

al. (1990); and (6) Armentrout and Clement (1990).

Figure

11. Curves showing sea level change, fauna discontinuities, and sequence

boundaries for the world (columns 1, 2, 3) (Haq et al., 1988), the U.S.A.

margins of the Gulf of Mexico (columns 4, 5, 6), and the Columbus Basin,

Trinidad. Some sequence boundaries in the Columbus Basin appear correlative with

time-equivalent sea level falls and associated sequence boundaries identified in

other areas of the world. These sequence boundaries in the Columbus Basin are

most likely a function of eustatic base-level change (E); others appear to have

a more local tectonic origin (T). The tectonic nature of these boundaries is

supported by the presence in some wells of Cretaceous, Eocene, and Oligocene

fauna and flora identified as reworked in association with these boundaries (Pocknall

et al., 1999). Sources for the curves are (1) Beard et al. (1982); (2) Lamb et

al. (1987); (3) Haq et al. (1988); (4) Wornhardt and Vail (1990); (5) Pacht et

al. (1990); and (6) Armentrout and Clement (1990).

Figure

12. Illustration of a single lower Pleistocene megasequence deposited across

the Southeast Galeota (SEG),

Figure

12. Illustration of a single lower Pleistocene megasequence deposited across

the Southeast Galeota (SEG),  East

East Queen's Beach (EQB), and

Queen's Beach (EQB), and  East

East Mayaro (EM)

areas between the JLS (T1) and the HLS (top surface). This sequence includes

many of the

Mayaro (EM)

areas between the JLS (T1) and the HLS (top surface). This sequence includes

many of the  hydrocarbon

hydrocarbon productive sands of

productive sands of  East

East Mayaro field and is bounded in

the proximal direction by the G fault (G) and in the distal direction by a lower

Pleistocene counterregional surface moving along a mobile shale body located

northeastward of the EM1 and EM2 wells (Figure 4).

Mayaro field and is bounded in

the proximal direction by the G fault (G) and in the distal direction by a lower

Pleistocene counterregional surface moving along a mobile shale body located

northeastward of the EM1 and EM2 wells (Figure 4).

Figure

13. Illustration of the timing of formation (from oldest to youngest, a to b

to c, respectively) of various aspects of a typical megasequence across the gas

trend area from Cassia field (shown by the WSEG well [Figure

4]; southwest)

to

Figure

13. Illustration of the timing of formation (from oldest to youngest, a to b

to c, respectively) of various aspects of a typical megasequence across the gas

trend area from Cassia field (shown by the WSEG well [Figure

4]; southwest)

to  East

East Mayaro field (shown by the EM wells [Figure

4]; northeast). See text

for detailed discussion. CRG = counterregional guideplane.

Mayaro field (shown by the EM wells [Figure

4]; northeast). See text

for detailed discussion. CRG = counterregional guideplane.

Click here to view sequence of images in Figure 13.

Figure

14. Illustration of the similarities and differences that exist between the

tectonostratigraphic characteristics of the Columbus Basin, Trinidad,

Figure

14. Illustration of the similarities and differences that exist between the

tectonostratigraphic characteristics of the Columbus Basin, Trinidad,  model

model (a)

and that of Evamy et al. (1978) Niger Delta, Nigeria,

(a)

and that of Evamy et al. (1978) Niger Delta, Nigeria,  model

model (b). Note the

bidirectional wedging of sediments, both distal toward the shale diapir and

proximal toward the normal fault, in the Columbus Basin, as compared with the

unidirectional wedging proximally that occurs in the Niger Delta.

(b). Note the

bidirectional wedging of sediments, both distal toward the shale diapir and

proximal toward the normal fault, in the Columbus Basin, as compared with the

unidirectional wedging proximally that occurs in the Niger Delta.

Figure

15. Illustration of the difference in alignment, deep to shallow, of

structural crests in some fields of (a) the Columbus Basin, Trinidad, vs. (b)

the Niger Delta, Nigeria (after Weber [1987]).

Figure

15. Illustration of the difference in alignment, deep to shallow, of

structural crests in some fields of (a) the Columbus Basin, Trinidad, vs. (b)

the Niger Delta, Nigeria (after Weber [1987]).

Figure

16. Electric log from the

Figure

16. Electric log from the  East

East Mayaro 3 well (see Figure 4

for location),

illustrating

Mayaro 3 well (see Figure 4

for location),

illustrating  hydrocarbon

hydrocarbon -bearing transgressive system tract (TST) waste-zones in

the 23 sand interval vs. the late-highstand systems tract (HST) to lowstand

systems tract (LST)

-bearing transgressive system tract (TST) waste-zones in

the 23 sand interval vs. the late-highstand systems tract (HST) to lowstand

systems tract (LST)  hydrocarbon

hydrocarbon accumulations in the higher quality 24 sand

interval.

accumulations in the higher quality 24 sand

interval.

General Geology of the Columbus Basin

Character of the Upper Tertiary Orinoco Delta

Faunal and Floral Biostratigraphy and Environments of Deposition

Depositional Environments and Facies

Rates of Sediment  Accumulation

Accumulation

Sequence Stratigraphy of the Columbus Basin

Influence of Tectonics on Stratigraphic Sequence Development

Tectonostratigraphic  Model

Model

Comparison with the Niger Delta

Structural Control on Depositional Systems and Accommodation Space

Implications and Recommendations for Exploration in the Columbus Basin

The Columbus Basin, defined by Leonard (1983), forms the easternmost part of

the Eastern Venezuela Basin (EVB) off the  east

east coast of Trinidad (Figure

1). The basin is bordered on the north by the Darien Ridge, an offshore

extension of Trinidad's Central Range, and on the south by the stable Delta

Amacuro Platform (Figure 2). To

the

coast of Trinidad (Figure

1). The basin is bordered on the north by the Darien Ridge, an offshore

extension of Trinidad's Central Range, and on the south by the stable Delta

Amacuro Platform (Figure 2). To

the  east

east of the basin is the South American continental shelf, and to the west,

onshore Trinidad and the EVB. Downwarping of the west margin of the EVB began

during the Oligocene in association with subduction of the Caribbean plate from

the north (Parnaud et al., 1995). A diachronous series of en echelon

of the basin is the South American continental shelf, and to the west,

onshore Trinidad and the EVB. Downwarping of the west margin of the EVB began

during the Oligocene in association with subduction of the Caribbean plate from

the north (Parnaud et al., 1995). A diachronous series of en echelon

east

east -northeast-oriented depocenters developed across the northern South America

region in response to this downwarping as the foredeep migrated eastward. The

depocenters were successively filled by more than 40,000 ft (>12,000 m) of

sediment, the Columbus Basin being the easternmost depocenter (Figure

1). The Orinoco River has been the primary source of sediment filling these

depocenters; since the mid-Miocene, its course has been heavily influenced by

the progressive downwarping of the eastward-migrating foreland basin (Hedberg,

1950; Hoorn et al., 1995; Diaz de Gamero, 1996). Local tectonic features, such

as the Urica arch (Figure 1), were

intermittently active during the Miocene to Holocene, significantly affecting

the character of the proto-Orinoco River feeding the Columbus Basin (Erlich and

Barrett, 1994). In addition, phases of thrusting and thrust-load subsidence

along the

-northeast-oriented depocenters developed across the northern South America

region in response to this downwarping as the foredeep migrated eastward. The

depocenters were successively filled by more than 40,000 ft (>12,000 m) of

sediment, the Columbus Basin being the easternmost depocenter (Figure

1). The Orinoco River has been the primary source of sediment filling these

depocenters; since the mid-Miocene, its course has been heavily influenced by

the progressive downwarping of the eastward-migrating foreland basin (Hedberg,

1950; Hoorn et al., 1995; Diaz de Gamero, 1996). Local tectonic features, such

as the Urica arch (Figure 1), were

intermittently active during the Miocene to Holocene, significantly affecting

the character of the proto-Orinoco River feeding the Columbus Basin (Erlich and

Barrett, 1994). In addition, phases of thrusting and thrust-load subsidence

along the  east

east margin of the northern Andes Cordillera influenced the discharge

rate and sediment load of the river throughout the late Tertiary (Hoorn et al.,

1995).

margin of the northern Andes Cordillera influenced the discharge

rate and sediment load of the river throughout the late Tertiary (Hoorn et al.,

1995).

The EVB is a prolific  hydrocarbon

hydrocarbon province, having produced more than 7

billion bbl of oil in the Venezuelan part of the basin (Erlich and Barrett,

1994) (Figure 1). Production has

come mainly from Oligocene to Miocene fluvial-deltaic and shallow-marine

deposits (Figure 3). Onshore and

offshore

province, having produced more than 7

billion bbl of oil in the Venezuelan part of the basin (Erlich and Barrett,

1994) (Figure 1). Production has

come mainly from Oligocene to Miocene fluvial-deltaic and shallow-marine

deposits (Figure 3). Onshore and

offshore  hydrocarbon

hydrocarbon exploration in Trinidad has been active since the 1860s,

and the first commercial production was established in 1902 (Tiratsoo, 1986).

Eastern offshore exploration for hydrocarbons in the Columbus Basin began in the

late 1960s, resulting in the discovery of Teak field (SDT2) (Figure

4). Subsequent activity has resulted in more than 2.6 billion bbl of oil

having been produced in these areas from fluvial-deltaic, shallow-marine, and

deep-marine turbidite deposits of the Miocene-Pliocene (Rodrigues, 1998).

Further estimates indicate more than 3.27 billion bbl of oil in place and 20 tcf

of gas in place.

exploration in Trinidad has been active since the 1860s,

and the first commercial production was established in 1902 (Tiratsoo, 1986).

Eastern offshore exploration for hydrocarbons in the Columbus Basin began in the

late 1960s, resulting in the discovery of Teak field (SDT2) (Figure

4). Subsequent activity has resulted in more than 2.6 billion bbl of oil

having been produced in these areas from fluvial-deltaic, shallow-marine, and

deep-marine turbidite deposits of the Miocene-Pliocene (Rodrigues, 1998).

Further estimates indicate more than 3.27 billion bbl of oil in place and 20 tcf

of gas in place.

The complex interplay of regional tectonics, extension normal faulting, high

rates of sediment supply, and sea level change has created a complicated

stratigraphy in the Columbus Basin, one that resists many standard methods of

sequence stratigraphic analysis. Classic sequence analysis techniques and models

that were developed in passive-margin settings (Vail et al., 1977; Posamentier

and Vail, 1988) typically operate on the assumption that sea level has been the

dominant mechanism driving stratigraphic sequence development. Application of

sequence stratigraphic models from foreland-basin (Swift et al., 1987; Devlin et

al., 1993; Posamentier and Allen, 1993) or passive-margin settings (Mitchum et

al., 1991) oversimplifies the complexity of transpressional settings.

Transpressional basins, such as the Columbus Basin, contain elements of thrust

belt-foreland models, the growth-normal faulting and mobile substrate movement

common to passive-margin settings, and extension structuring common along

strike-slip plate margins (Babb and Mann, 1999). Structural complexity,

syndepositionally active structures, high rates of sedimentation, and

high-frequency sea level change all influenced the Pliocene-Pleistocene sequence

stratigraphy of the Columbus Basin. The dearth of understanding of the relative

magnitude of influence these elements have on stratigraphic sequence geometry,

character, and distribution has led to mixed exploration and production results.

Understanding of the true age and nature of the basin's stratigraphic section

will decrease uncertainty in reservoir and seal prediction,

hydrocarbon

hydrocarbon -generation modeling, migration analysis, and pressure prediction, as

well as many other variables involved in an integrated exploration solution. As

petroleum exploration in the basin matures, there is a need for more detailed

understanding of the reservoir, seal geometry and distribution, and the timing

of all elements that make up the

-generation modeling, migration analysis, and pressure prediction, as

well as many other variables involved in an integrated exploration solution. As

petroleum exploration in the basin matures, there is a need for more detailed

understanding of the reservoir, seal geometry and distribution, and the timing

of all elements that make up the  hydrocarbon

hydrocarbon system. The syndepositional nature

of structure in the basin has created opportunities for the occurrence of

stratigraphic and combination stratigraphic/structure plays. However, these play

types cannot be pursued with any degree of confidence at the current level of

understanding stratigraphic sequence development in the Columbus Basin.

system. The syndepositional nature

of structure in the basin has created opportunities for the occurrence of

stratigraphic and combination stratigraphic/structure plays. However, these play

types cannot be pursued with any degree of confidence at the current level of

understanding stratigraphic sequence development in the Columbus Basin.

The goals of this article are to

- Detail a chronostratigraphic framework of the Columbus Basin;

- Outline a tectonostratigraphic

model

model for sequence development in the Pliocene and Pleistocene of the

Columbus Basin, one that may serve to describe sequence stratigraphic

development in other transpressional settings;

for sequence development in the Pliocene and Pleistocene of the

Columbus Basin, one that may serve to describe sequence stratigraphic

development in other transpressional settings; - Compare and contrast the Columbus Basin with similar settings, such as the Niger Delta; and

- Discuss implications of the results of this work on exploration in the Columbus Basin and other transpressional settings.

A multidisciplinary data set, including well logs, palynology, benthic and planktonic foraminifera, oxygen isotopes, lithologic samples, core and outcrop descriptions, and seismic-line interpretations, was used to develop a chronostratigraphic and sequence stratigraphic framework for the Pliocene-Pleistocene deposits of the Columbus Basin. Data from 41 wells included paleontology assemblages and abundance and occurrence data, as well as gamma-ray, resistivity, and caliper logs. These data formed the ground truth for correlation of additional logs in the basin and were integrated with thousands of kilometers of interpreted two-dimensional (2-D) and three-dimensional (3-D) seismic lines to construct regional chronostratigraphic cross sections and to generate a chronostratigraphic framework for the Pliocene-Pleistocene of the basin.

The methodology employed in this study included the following:

- Reconciliation of multiple data types into an integrated depositional sequence analysis for each well in the study area. This required recognition of surfaces of reworking, flooding, and condensed sedimentation, as noted from well log motif and seismic data. In addition, casing points, sampling intervals, and drilling data were used to resolve in-situ from non-in-situ paleostratigraphic data and to refine environments of deposition. Key data for detailed interpretation of environments of deposition included benthic foraminifera and palynomorph assemblages, well log motifs, observable seismic facies, and location of specific wells within the context of the regional paleogeography.

- Use of palynomorph and planktonic foraminifera first uphole occurrence, extinction, and acme events in each well to age-date stratigraphic horizons.

- Use of seismic data to correlate specific time markers between wells within each fault block and to identify significant event surfaces within each fault block (bypass surfaces and basinward equivalent conformities, transgressive surfaces, condensed sections, flooding events, etc.).

- Definition of parasequences within each fault block, using identified key event surfaces and parasequence bounding surfaces.

- Reconciliation of the chronostratigraphic framework of each fault block with adjacent fault blocks by using seismic and well-data loops to ensure cross-fault correlation of time-equivalent depositional sequences and to construct regional chronostratigraphic cross sections.

- Correlation of chronostratigraphic packages between fault blocks, definition of basinwide depositional sequences, and construction of chronostratigraphic diagrams.

- Integration of

chronostratigraphy and paleogeography with seismic data to develop a

tectonostratigraphic

model

model and to constrain the time of movement of major

structures in the basin.

and to constrain the time of movement of major

structures in the basin.

General Geology of the Columbus Basin

The Columbus Basin is located along the south margin of the obliquely

converging Caribbean-South American plate boundary, a zone of intense structural

deformation (Figure 1) (Speed,

1985; Robertson and Burke, 1989). Primary structural elements in the basin

include (1) a series of transpressional northeast-southwest-trending ridges and

(2) northwest-southeast-oriented, down-to-the-northeast, normal faults (Figures

2, 5). Most reservoirs have

been discovered where compressional deep ridges are juxtaposed against major

normal growth faults to produce structural closure. Fold axial traces and normal

fault orientation, both less than 45~ to the plate boundary zone, indicate a

transpressional rather than a transcurrent or transtensional setting for the

Columbus Basin. Gravity tectonics along a thin-skinned detachment surface

dipping to the  east

east -northeast, however, may have also influenced the orientation

of these structural features, as well as masked the appearance of other

structures associated with these regimes, such as positive or negative flower

structure. The interpretation of a transpressional structural regime for this

area was well documented by Babb and Mann (1999), and the reader is referred to

this article for many data documenting the structural framework of the

Caribbean-South American margin in this area. Because a more detailed discussion

is beyond the scope of this article, the reader is additionally referred to

Perez and Aggarwal (1981), Robertson and Burke (1989), Erlich and Barrett

(1990), Ave Lallemant (1991), and Russo and Speed (1992).

-northeast, however, may have also influenced the orientation

of these structural features, as well as masked the appearance of other

structures associated with these regimes, such as positive or negative flower

structure. The interpretation of a transpressional structural regime for this

area was well documented by Babb and Mann (1999), and the reader is referred to

this article for many data documenting the structural framework of the

Caribbean-South American margin in this area. Because a more detailed discussion

is beyond the scope of this article, the reader is additionally referred to

Perez and Aggarwal (1981), Robertson and Burke (1989), Erlich and Barrett

(1990), Ave Lallemant (1991), and Russo and Speed (1992).

The sedimentary column of the eastern Columbus Basin consists mainly of thick

Pleistocene and Pliocene strata overlying mobile, pre-Pliocene shales.

Cretaceous marine facies deposited along a generally west-trending to

east

east -trending paleo-Cretaceous shelf break dip deep northward into the

subsurface and underlie the Tertiary sediments (Persad et al., 1993; Pindell and

Erikson, 1993; Heppard et al., 1998) (Figure

5). Although they remain undrilled in the Columbus Basin, the mobile units

of pre-Pliocene age are thought to consist dominantly of Miocene shales and

perhaps a thin veneer of Paleocene, Eocene, and Oligocene deposits. This

interpretation is supported by penetrations of pre-Pliocene units to the north

(Robertson and Burke, 1989) and south (Di Croce et al., 1999) of the basin, as

well as onshore Trinidad (Persad et al., 1993).

-trending paleo-Cretaceous shelf break dip deep northward into the

subsurface and underlie the Tertiary sediments (Persad et al., 1993; Pindell and

Erikson, 1993; Heppard et al., 1998) (Figure

5). Although they remain undrilled in the Columbus Basin, the mobile units

of pre-Pliocene age are thought to consist dominantly of Miocene shales and

perhaps a thin veneer of Paleocene, Eocene, and Oligocene deposits. This

interpretation is supported by penetrations of pre-Pliocene units to the north

(Robertson and Burke, 1989) and south (Di Croce et al., 1999) of the basin, as

well as onshore Trinidad (Persad et al., 1993).

Reservoirs off the  east

east coast of Trinidad are all Pliocene-Pleistocene in

age, either trapped in four-way structural closures or trapped as downthrown or

upthrown faulted three-way closures. The strata are marine and terrigenous

clastic sediments deposited as a series of northeastward-prograding

strand-plain/nearshore sediment wedges and downdip slope/basin fan wedges (Wood

et al., 1994; Wood, 1995, 1996; Heppard et al., 1998; Di Croce et al., 1999).

These extremely thick, prograding megasequences were rapidly deposited;

coast of Trinidad are all Pliocene-Pleistocene in

age, either trapped in four-way structural closures or trapped as downthrown or

upthrown faulted three-way closures. The strata are marine and terrigenous

clastic sediments deposited as a series of northeastward-prograding

strand-plain/nearshore sediment wedges and downdip slope/basin fan wedges (Wood

et al., 1994; Wood, 1995, 1996; Heppard et al., 1998; Di Croce et al., 1999).

These extremely thick, prograding megasequences were rapidly deposited;

accumulation

accumulation rates during the Pliocene-Pleistocene ranged from 7 to 20 ft (2 to

6 m) per thousand years. These high

rates during the Pliocene-Pleistocene ranged from 7 to 20 ft (2 to

6 m) per thousand years. These high  accumulation

accumulation rates resulted from high

sediment supply from the proto-Orinoco and rapid generation of accommodation

space by extension tectonics.

rates resulted from high

sediment supply from the proto-Orinoco and rapid generation of accommodation

space by extension tectonics.

Character of the Upper Tertiary Orinoco Delta

The modern Orinoco Delta is a complex hybrid deltaic system composed of distinctly defined zones of wave-dominated, tide-dominated, and river-dominated morphology (Warne et al., 1999a, b). The lower Tertiary Orinoco Delta differed in character, however, from its modern successor. The Orinoco Delta of the later Tertiary was a wave-dominated delta system prograding onto a storm-influenced and current-influenced shelf (Figures 6, 7). The delta occupied successively more eastward positions on the shelf throughout the late Tertiary, and upon reaching each successive shelf-edge break, the deltaic system became more aggradational in response to increased accommodation space. The shelf-to-slope break was oversteepened as a result of bed rotation along the counterregional glide surface formed on the landward side of rising shale diapirs. Such rotation is reflected in seismic data by the downdip thickening of sediments into the remnant shale bulge, as well as the drag exhibited at the toe of the progradational wedges (Figure 5). Most of the basin's accommodation was focused in northwest-southeast-oriented depocenters very near the shelf-slope break. Low accommodation on the shelf resulted in the paleo-Orinoco Delta repeatedly prograding to the edge of the shelf. This lowstand delta was exposed to the reworking processes of the open ocean, having little or no outboard shelf to attenuate wave activity. The cuspate, strike-continuous (northwest-to-southeast), cleanly winnowed reservoir sands of the Columbus Basin are a product of this setting. Modern analogs to this style of deltaic sedimentation are the Sao Francisco Delta, offshore Brazil (Dominguez, 1996), and the Nayarit Coast, offshore Mexico. Ancient examples include the lower Wilcox Formation of the Tertiary Gulf of Mexico (Galloway et al., 1982).

Few if any incised valleys that must have fed the lowstand Orinoco

Delta can be identified on 2-D or 3-D seismic lines. Paleoenvironmental data

from fauna and flora, however, indicate that brackish to terrestrial conditions

did exist across the basin during periods of lowstand delta deposition to the

east

east . Local tectonic activity at the depositional shelf break focused lowstand

accommodation space in shelf-break locations. High rates of sediment supply

filled all available proximal accommodation space, creating a broad, low,

sloping-gradient coastal plain. As a consequence, the Orinoco Delta distributary

system was most likely characterized by dispersed, low-velocity flows and low

stream powers that were forced to transport large volumes of sediment to

shelf-edge-break depocenters. Low slopes along the continental margin mean

little change in base level as sea level fell, resulting in the wide, shallow,

distributary-channel incision in the coastal plain. Truncation of older shelf

deposits by feeder valleys is shallow, commonly below the seismic resolution. In

some locations, such as the

. Local tectonic activity at the depositional shelf break focused lowstand

accommodation space in shelf-break locations. High rates of sediment supply

filled all available proximal accommodation space, creating a broad, low,

sloping-gradient coastal plain. As a consequence, the Orinoco Delta distributary

system was most likely characterized by dispersed, low-velocity flows and low

stream powers that were forced to transport large volumes of sediment to

shelf-edge-break depocenters. Low slopes along the continental margin mean

little change in base level as sea level fell, resulting in the wide, shallow,

distributary-channel incision in the coastal plain. Truncation of older shelf

deposits by feeder valleys is shallow, commonly below the seismic resolution. In

some locations, such as the  East

East Queen's Beach (EQB) area (Figure

4), late-stage pop-up structures may have confined distributaries to

specific pathways, resulting in point-source deltas, but for the most part late

Tertiary Orinoco deltas were line-source distributary systems producing

line-source slope deposits. Slope and basinal gravity deposits were, however,

subject to direction by submarine topography building out in front of the shelf

break.

Queen's Beach (EQB) area (Figure

4), late-stage pop-up structures may have confined distributaries to

specific pathways, resulting in point-source deltas, but for the most part late

Tertiary Orinoco deltas were line-source distributary systems producing

line-source slope deposits. Slope and basinal gravity deposits were, however,

subject to direction by submarine topography building out in front of the shelf

break.

Upper Cretaceous organic-rich mudstones acted as source rock for many of the hydrocarbons in Trinidad (Rodrigues, 1988; Talukdar et al., 1988; Heppard et al., 1990). Thicknesses of as much as 3280 ft (1000 m) of the Cretaceous source interval have been penetrated in the Soldado 189 well, Gulf of Paria (Figure 1). Cretaceous organic matter exhibits both terrigenous and marine organic affinities; total organic carbon (TOC) values range from 2 to 12% (Persad et al., 1993).

Previous workers have suggested two primary mechanisms for  hydrocarbon

hydrocarbon migration within the Columbus Basin. Strong evidence suggests that the large,

down-to-the-basin, normal faults serve as primary migration pathways for

hydrocarbons (Figure 5). Such

migration routes have been documented in the Columbus Basin, in the upper 2300

ft (700 m) of strata (Wood and Nash, 1995), and similar mechanisms are thought

to be active at depth (Leonard, 1983; Heppard et al., 1990, 1998). Faults in

Miocene strata in southern Trinidad appear to have acted as primary migration

conduits into Miocene and Pliocene reservoirs (Persad et al., 1993). All

offshore Trinidad fields are associated directly or indirectly with deep faults,

some of which are thought to extend into underlying Cretaceous source rocks

(Leonard, 1983). The occurrence of numerous

migration within the Columbus Basin. Strong evidence suggests that the large,

down-to-the-basin, normal faults serve as primary migration pathways for

hydrocarbons (Figure 5). Such

migration routes have been documented in the Columbus Basin, in the upper 2300

ft (700 m) of strata (Wood and Nash, 1995), and similar mechanisms are thought

to be active at depth (Leonard, 1983; Heppard et al., 1990, 1998). Faults in

Miocene strata in southern Trinidad appear to have acted as primary migration

conduits into Miocene and Pliocene reservoirs (Persad et al., 1993). All

offshore Trinidad fields are associated directly or indirectly with deep faults,

some of which are thought to extend into underlying Cretaceous source rocks

(Leonard, 1983). The occurrence of numerous  hydrocarbon

hydrocarbon seeps on the island

supports the notion that hydrocarbons are migrating directly along faults. Other

workers have suggested that most faulting in the fields postdates generation and

migration of hydrocarbons (Heppard et al., 1998). They have proposed an

alternative mechanism, namely, that hydraulically induced fractures within a

highly overpressured section are the conduit for migrating hydrocarbons (Miller,

1995; Heppard et al., 1998). A third possible migration pathway is via carrier

beds, which downlap onto or structurally abut onto the underlying source rocks

across glide planes (Figure 5) (Heppard

et al., 1998). In this scenario, updip migration is also aided by significant

overpressuring of fluids in the section. Most hydrocarbons in the Columbus Basin

probably migrate through some combination of these three mechanisms. The result

is a stair-step pattern of migration, whose tortuous nature helps explain the

fractionated and variable character of the hydrocarbons in Columbus Basin

reservoirs (Ross and Ames, 1988; Talukdar et al., 1990; Persad et al., 1993).

seeps on the island

supports the notion that hydrocarbons are migrating directly along faults. Other

workers have suggested that most faulting in the fields postdates generation and

migration of hydrocarbons (Heppard et al., 1998). They have proposed an

alternative mechanism, namely, that hydraulically induced fractures within a

highly overpressured section are the conduit for migrating hydrocarbons (Miller,

1995; Heppard et al., 1998). A third possible migration pathway is via carrier

beds, which downlap onto or structurally abut onto the underlying source rocks

across glide planes (Figure 5) (Heppard

et al., 1998). In this scenario, updip migration is also aided by significant

overpressuring of fluids in the section. Most hydrocarbons in the Columbus Basin

probably migrate through some combination of these three mechanisms. The result

is a stair-step pattern of migration, whose tortuous nature helps explain the

fractionated and variable character of the hydrocarbons in Columbus Basin

reservoirs (Ross and Ames, 1988; Talukdar et al., 1990; Persad et al., 1993).

Faunal and Floral Biostratigraphy and Environments of Deposition

Regional and local factors render more difficult the task of applying conventional biostratigraphy to define the Pliocene-Pleistocene chronostratigraphic framework in the Columbus Basin. The Orinoco and proto-Orinoco rivers have drained the Andean highlands since the early Miocene, but only since the late Miocene has the Orinoco had an established outlet through the Columbus Basin (Hoorn, 1995; Hoorn et al., 1995; Diaz de Gamero, 1996) (Figure 1). The river and its associated marginal and deep-marine depositional systems have supplied more than 45,000 ft (14 km) of post-Miocene sediment into the basin (Erlich and Barrett, 1990). This rapid rate of sedimentation has reduced the number of nannofossils and planktonic foraminifera species that are used in other basins for chronostratigraphic correlation. In addition, the overthick section creates time-resolution problems across the basin because age-range-limited fauna or flora are scarce relative to the thicknesses of strata. Thickening of stratal packages across regional growth faults creates the need for some form of time marker to aid in accurate correlation (Leonard, 1983). Those planktonic faunal markers that are present commonly suffer from suppressed extinction because of the high sedimentation rates, causing them to appear much shorter lived than their worldwide ranges. The high rates of sediment supply, high marine energy levels, and the incising nature of the riverine-sediment transport system within the basin also complicate faunal and floral correlations by reworking microfossils in many environments. This reworking not only confuses age relationships but also contaminates the in-situ environmental assemblages. Active thrusting on the island of Trinidad during the late Pliocene and the resulting high-relief terrain also obscure age relationships by providing reworked microfossils of all ages to the active depositional system. Finally, the rapid rates and high volumes of sediment being deposited in the basin have produced a very young and poorly consolidated section that is prone to downhole caving during drilling, resulting in spurious tops and bases (Pocknall et al., 1999). Data types must be integrated carefully to establish true ages and depositional environments of the sections of interest.

Faunal and floral extinctions and evolutions, as well as some abundance acme, derived from data in more than 41 wells (Figure 4) have been used in the Columbus Basin to aid in creating a chronostratigraphic framework for the Pliocene-Pleistocene. The age significance of planktonic foraminifera and palynomorph occurrences is detailed in Pocknall et al. (1996, 1999) (Figure 8).

Depositional Environments and Facies

In addition to the use of palynomorphs and planktonic foraminifera as age indicators, assemblage and abundance data of these fossils have been used, along with geophysical log motif, to define five distinct depositional facies that characterize the Columbus Basin: (1) fluvial/estuarine/transitional barrier island, (2) prograding shoreface, (3) slope fan, (4) basin-floor fan, and (5) condensed section facies. Details of the faunal and floral assemblages and their environments that characterize these elements are detailed in Pocknall et al. (1999) and are summarized in a following section.

Fluvial/Estuarine/Transitional Barrier

Fluvial/estuarine/transitional barrier depositional facies are composed of sediments deposited either subaerially or within the zone of tidal influence. Environments include active and abandoned channel fills, flood plains, swamps, estuarine sand bars, lagoons, beaches, marshes, and tidal flats. Mangrove pollen (derived from Rhizophora, Avicennia, and Pelliciera) is common in estuarine valley-fill sediments. Other significant components include the benthic foraminifera Milliammina telemaquensis, Arenoparrella mexicana, Ammonia beccarii, and Ammobaculities dilitatus; pollen derived from swamp plants such as Symphonia (Pachydermites diederixi) and Ceratopteris (Magnastriatities howardi); and Gramineae pollen derived from the swamp-marsh grass.

Log character for the fluvial and transitional barrier-complex facies consists of a blocky or occasional upward-fining motif commonly having a serrated texture. Sandier units are generally interbedded with alluvial overbank, fine-grained deposits and crevasse splay sands and fine-grained estuarine facies. In some wells, these finer grained intervals are several hundreds of feet thick. The sands that characterize these facies are well sorted and friable and in outcrop exhibit ripples, low-angle cross-beds, and some bidirectional cross-bedding. Interbedded dark-black, organic-rich siltstones and silty mudstones show ripples and wavy laminations. Reworked shells and plant and organic material are common. In outcrop, these facies exhibit soft sediment deformation. Little evidence of coal or lignite can be found in cutting samples from these facies, but in outcrop coals and laterally continuous lignites both are not uncommon.

Prograding Shoreface

Prograding shoreface consists of the lower, middle, and upper shoreface subfacies deposited predominantly below sea level and within the zone of wave, tide, and storm influence. Faunal assemblages reflect an overall upward-shallowing succession from Buliminella spp., Planulina foveolata, and Bolivina multicostata, to increasing occurrences of Uvigerina peregrina in the middle shelf, and, finally, Amphistegina lessonii, Nonionella atlantica, and Bolivina spinata in the inner shelf sediments. Finer grained shelfal units are characterized by abundances of dinoflagellates, whereas sandier shelf systems show a decrease in dinoflagellates. In outcrop these facies consist of thick, clean, fine-grained sands (10 to 20 ft [3 to 6 m]) separated by interbedded silts and clays. Isolated beds of coarse-grained to medium-grained sand can occur at the top of upward-coarsening sequences. Sorting varies from moderate to good as one moves distally in the shoreface system. Thicker sands, having sharp scoured bases, contain abundant large-scale and medium-scale trough cross-beds. Thick, fine-grained sandstone/siltstone intervals have abundant vertical burrowing and shell fragments. Ophiomorpha dominate the ichnofauna assemblage. Silt/sand intervals underlying coarser grained sands contain abundant evidence of dewatering structures and convoluted bedding. Log motifs of these facies are characterized by an upward-coarsening stack of progradational parasequences whose final top is commonly sharply truncated and whose thickness may range to almost 1000 ft (330 m).

Slope Fan

Slope-fan sediments are deposited as slope fans and slope-leveed channel complexes in depths ranging from 600 to 3000 ft (200 to 1000 m) of water. Assemblages characteristic of these facies include the consistent occurrence of Guppyella miocenica, Trochamina trincherasensis, Cyclammina cancellata, planktonic foraminifera, and the occasional presence of Haplophragmoides carinatum, H. narivaensis, Bathysiphon spp., and Reticulophragmium venezuelanum. Transported Rhizophora pollen is commonly seen in high numbers in these facies. These facies are poorly exposed in outcrop and core data are extremely limited. They are dominantly composed of gray, micaceous, highly calcareous silts and silty clays, rich in foraminifera, interbedded with fine-grained, laminated, micaceous sands containing some carbonaceous streaks. Sands are swaley bedded, having abundant bioturbation, and coarsen upward from very fine to fine. Shales show some soft sediment deformation, and siltstones show evidence of low-angle cross-bedding. Well logs in these deposits are characterized by ratty, sand-shale log character, which typically fines upward in packages as thick as 1000 ft (330 m).

Basin-Floor Fan

Basin-floor-fan facies are deposited in very deep water (>3000 ft [1000 m]) near the toe of the slope. They contain much reworked middle to outer neritic fauna mixed with in-situ, deeper water, agglutinated fauna. In-situ fauna include common to abundant planktonics; benthic forms include Recurvoides obsoletum, Cyclammina cancellata, Ammodiscus spp., and Alveovalvulina suteri. Flora present include abundances of dinoflagellates and land-derived Rhizophora and various species of fern spores. Basin-floor-fan facies have not been described in outcrop or core. Well log motif of these sediments is sharp to sharply gradational at the base, overlain by several stacked packages (each ~100 ft [~30 m] thick), which show a blocky to slightly serrated character.

Condensed Section

Deep-water, fine-grained silts and shales compose the condensed section facies. Consistent and abundant Glomospira charoides, Alveovalvulina suteri, and Reticulophragmium venezuelanum are found in these facies. Dinoflagellates are common and commonly consist of monospecific assemblages of Nematosphaeropsis lemniscata. Well logs indicate very low resistivities and high (hot) gamma signatures associated with these deposits. Although condensed sections have not been cored in the basin, they are thought, on the basis of log character, to consist dominantly of silts and clay.

Rates of Sediment  Accumulation

Accumulation

Sediment supply throughout the Pliocene and Pleistocene in the Columbus Basin

was enormous, having the bulk of these sediments derived from the Andes

Mountains and associated regions far to the southwest of Trinidad. Rates of

sediment  accumulation

accumulation in the basin during this time period surpassed those seen

in other Tertiary deltaic settings, such as the Mississippi, Niger, or Nile

deltas. Sediment

in the basin during this time period surpassed those seen

in other Tertiary deltaic settings, such as the Mississippi, Niger, or Nile

deltas. Sediment  accumulation

accumulation rates of as much as 15 to 20 ft (5 to 6 m) per

1000 yr are typical across the basin, having rates of as much as 26 ft (8 m) per

1000 yr in some depocenters (Figure 7).

Evidence of these rapid rates of

rates of as much as 15 to 20 ft (5 to 6 m) per

1000 yr are typical across the basin, having rates of as much as 26 ft (8 m) per

1000 yr in some depocenters (Figure 7).

Evidence of these rapid rates of  accumulation

accumulation can be seen in the sedimentary

structures that characterize the upper Tertiary clastic section. Outcrops of

Pliocene strata on the island of Trinidad exhibit dewatering structures, flame

structures of as much as 3 ft (1 m) in height, fluidized flow features, large

ball and pillow features, and large-scale convoluted bedding (Figures

9a, 9b). Deposits

characterized by such features are commonly mistaken for deeper marine,

mass-flow facies. However, careful examination of these deposits reveals

coinciding ripple cross-laminations, climbing ripples, large-scale trough

cross-beds, tidal bedding and in-situ shelfal ichnofauna (Skolithos),

some vertical burrows reaching as much as 5 ft (15 m) in length (Farrelly,

1987). All evidence supports an interpretation of a shallow-water, shelfal

setting for deposition of these units.

can be seen in the sedimentary

structures that characterize the upper Tertiary clastic section. Outcrops of

Pliocene strata on the island of Trinidad exhibit dewatering structures, flame

structures of as much as 3 ft (1 m) in height, fluidized flow features, large

ball and pillow features, and large-scale convoluted bedding (Figures

9a, 9b). Deposits

characterized by such features are commonly mistaken for deeper marine,

mass-flow facies. However, careful examination of these deposits reveals

coinciding ripple cross-laminations, climbing ripples, large-scale trough

cross-beds, tidal bedding and in-situ shelfal ichnofauna (Skolithos),

some vertical burrows reaching as much as 5 ft (15 m) in length (Farrelly,

1987). All evidence supports an interpretation of a shallow-water, shelfal

setting for deposition of these units.

Pliocene-Pleistocene sediments in the subsurface of the basin are virtually

unconsolidated. Sand porosities, even at burial depths exceeding 12,000 ft

(>3660 m), can have 25 to 35%; permeabilities of several hundreds of darcys

are not atypical. Overpressure problems exist throughout the basin and are

partly due to the rapidly deposited, stacked, shallow, clastic shelf deposits

overlying deeper outer-shelf and upper-slope facies (Heppard et al., 1998). All

of these characteristics are evidence of a depositional setting having extremely

rapid  accumulation

accumulation of sediment, occurring in a shallow-marine shelf setting.

of sediment, occurring in a shallow-marine shelf setting.

Sequence Stratigraphy of the Columbus Basin

A series of progradational clastic wedges form the Pliocene-Pleistocene

stratigraphic architectural package of the Columbus Basin (Figure

10). Development and character of these wedges are driven by three primary

elements, namely, tectonic activity, sediment supply, and marine-process

redistribution of sediments. Although they progress from oldest in the west to

youngest in the  east

east , the wedges exhibit many similar characteristics. Each

clastic wedge prograded from southwest to northeast across a part of the basin,

and each exhibits a high degree of lateral facies continuity along depositional

strike (northwest-southeast) (Figure 7).

Within each wedge, the depositional facies deepen progressively from southwest

to northeast, changing from (1) terrigenous fluvial/estuarine to (2)

progradational or aggradational shoreface to (3) middle and outer neritic shelf

to (4) slope and, finally, to (5) basinal facies over a distance of a few

kilometers. Distal parts of each prograding wedge downlap onto a mobile

substrate thought to be the top of thick Miocene marine shales (Figure

5). Megadepositional sequences (defined here as genetically related strata

bounded by regionally unconformable surfaces and their basinward correlative

conformities) average 10,000 to 12,000 ft (3000 to 3660 m) in thickness and

accumulated over relatively short periods (300,000 to 500,000 yr).

, the wedges exhibit many similar characteristics. Each

clastic wedge prograded from southwest to northeast across a part of the basin,

and each exhibits a high degree of lateral facies continuity along depositional

strike (northwest-southeast) (Figure 7).

Within each wedge, the depositional facies deepen progressively from southwest

to northeast, changing from (1) terrigenous fluvial/estuarine to (2)

progradational or aggradational shoreface to (3) middle and outer neritic shelf

to (4) slope and, finally, to (5) basinal facies over a distance of a few

kilometers. Distal parts of each prograding wedge downlap onto a mobile

substrate thought to be the top of thick Miocene marine shales (Figure

5). Megadepositional sequences (defined here as genetically related strata

bounded by regionally unconformable surfaces and their basinward correlative

conformities) average 10,000 to 12,000 ft (3000 to 3660 m) in thickness and

accumulated over relatively short periods (300,000 to 500,000 yr).

The megasequences are internally composed of five to eight progradational

parasequences, each averaging 550 to 980 ft (170 to 300 m) in thickness and

deposited over 50,000 to 100,000 yr (Figures

7, 10). These parasequences

contain reservoir sand bodies elongated along depositional strike. Facies within

each parasequence show a high degree of continuity in the depositional strike

direction but give way in a depositional dip direction (generally,

north-northeast) and within a few kilometers to deep-marine environments.

Parasequences are bounded by subregional regressive surfaces of erosion at their

bases and by subregional deepening events at their tops. These flooding events,

extensive along strike, result in  accumulation

accumulation of shales that make excellent

local seals, although these same shales are limited in the dip direction. They

therefore make poor correlation markers regionally (i.e., beyond the extent of a

single megasequence) and cannot be assumed to form high-quality seals across a

regional area.

of shales that make excellent

local seals, although these same shales are limited in the dip direction. They

therefore make poor correlation markers regionally (i.e., beyond the extent of a

single megasequence) and cannot be assumed to form high-quality seals across a

regional area.

Several key surfaces have been identified that are important in defining the megasequences that fill the Columbus Basin. From youngest to oldest, the regionally extensive surfaces (see Figures 10, 11) are (1) the near base Pliocene lowstand surface (LS) (NBPLS; 3.8 m.y.), (2) the base green LS (BGLS; 3.6 m.y.), (3) the base 8 sand LS (B8LS; 3.0 m.y.), (4) the base braided 2 sand LS (BB2LS; 2.3-2.4 m.y.), (5) the "N" LS (NLS; 2.0 m.y.), (6) the "J" LS (JLS or base Alnus lowstand; 1.78 m.y.), (7) the "H" LS (HLS; 1.5 m.y.), (8) the "F" LS (FLS; 1.3 m.y.), (9) the "F" transgressive surface (FTS; 1.2 m.y.), (10) the "E" LS (ELS; 1.0 m.y.), (11) the "D" LS (DLS; 0.8 m.y.), and (12) the "B" LS (BLS; 0.5 m.y.). These surfaces, with the exception of the FTS, mark basinwide episodes of basinward facies shifts and the progressive northeastward progradation of the Orinoco Delta system. Each episode is characterized by a rapid thickening of the stratigraphic section across successively eastward growth faults. Stratigraphic architecture within these fault blocks typically consists of deep-water marine clastics grading upsection into successively shallower shelf deposits and finally culminating in the sudden deposition of a series of stacked shelf parasequences (Figures 5, 10). Each sequence is capped by an unconformity associated with sediment bypass of the next-younger sequence. The FTS is a regionally extensive surface of deepening that corresponds to mid-Pleistocene marine flooding and landward translation of facies across the basin. This event initiated a distinct change in the basin toward higher frequency and larger magnitude translations of shoreline. The result is a series of large-magnitude lowstand progradational and highstand retrogradational events occurring across the area during the mid to late Pleistocene, having thin, shallow, widespread lowstand systems tracts alternating with thick, deep-water, transgressive shales (Figures 7, 10). The apparent increase in number of Pleistocene sequences (six) relative to Pliocene sequences (three) is superficial and a function of an increased abundance of key faunal and floral extinctions and first occurrences in the Pleistocene and uppermost Pliocene sections. This fact allows for a more detailed resolution of regionally extensive surfaces in the younger sections.

A second level in the hierarchy of surfaces is the subregionally extensive surfaces that developed as a function of more localized, structurally driven variations in accommodation space. The most pronounced of these localized surfaces are several large-magnitude marine unconformities that are somewhat angular and appear to divide the stratigraphic sections in each megasequence into a lower and an upper stratigraphic interval (Figures 5, 7). The lower stratigraphic intervals, characterized by a few specific shallowing events, are dominated by deeper marine facies. In contrast, the upper intervals are dominated by shallow-marine to fluvial facies, which contain abundant and distinct parasequence-scale shoreface cycles. These diachronous marine unconformities postdate the preceding maximum flooding surface and early highstand systems tract deposits. These unconformities appear to be regressive surfaces of marine erosion, which precede the most dramatic and continuous phases of late highstand progradation and aggradation in the basin. These surfaces form as a result of submarine tide, wave, and storm processes active on the depositional shelf. Similar regressive surfaces of marine erosion have been identified in both ancient and modern deposits (Plint, 1988; Posamentier et al., 1992; Posamentier and Allen, 1993), albeit not having the pronounced expression seen in the Columbus Basin, which is likely a function of syndepositional tectonism. Large-scale flexuring in the basin created a structural hinge along which marine erosion was enhanced.

Influence of Tectonics on Stratigraphic Sequence Development

The Columbus Basin regional chronostratigraphic framework discussed on preceding pages has been used to explain the complex relationships between larger, regionally extensive normal faults, mobile shale diapirs, and the deposition of large, clastic-rich megasequences that make up the stratigraphic architecture of the Columbus Basin.

Regional extension, associated with the oblique transpression of the

Caribbean plate to the north and the South American plate to the south, creates

sites of weakness for prograding sediments to load, further enhancing failure

along normal faults. The initiation of movement on these extension faults is

reflected in the stratigraphy on their downthrown side. There the stratigraphic

units most proximal to the downthrown side of the fault are deep-marine deposits

overlain by an initial progradational shallow-marine sand, overlain by another

deep flooding event marking early activity on the normal fault. Once the

tectonic accommodation space closest to the fault is filled, the succession

progrades  east

east of the proximal normal fault, eventually stalling near the

depositional shelf break. These faults, once initiated, bound the proximal side

of a single megasequence (Figure 12).

Aided by loading from the weight of progressive sediment deposition, mobile

shales are forced northeastward and begin to rise. Accommodation space is

generated beneath the basinal edge of the megasequence by shale withdrawal, and

subsidence begins along a counterregional glide plane, creating distal

accommodation space. Growth occurs across the proximal bounding faults (G in Figure

12) as sediments from the proto-Orinoco strive to fill proximal

accommodation space. Stratigraphic thickening likewise occurs toward the diapir

in response to progressive downward rotation of beds along the counterregional

glide-plane surface (Figure 12).

of the proximal normal fault, eventually stalling near the

depositional shelf break. These faults, once initiated, bound the proximal side

of a single megasequence (Figure 12).

Aided by loading from the weight of progressive sediment deposition, mobile

shales are forced northeastward and begin to rise. Accommodation space is

generated beneath the basinal edge of the megasequence by shale withdrawal, and

subsidence begins along a counterregional glide plane, creating distal

accommodation space. Growth occurs across the proximal bounding faults (G in Figure

12) as sediments from the proto-Orinoco strive to fill proximal

accommodation space. Stratigraphic thickening likewise occurs toward the diapir

in response to progressive downward rotation of beds along the counterregional

glide-plane surface (Figure 12).

A typical sequence of fault initiation and strata development is illustrated

in Figure 13. Fault G, active

pre-time marker 1 (T1), shows growth and terminates glide plane F at depth. The

sediment wedge to the northeast of fault G begins to be rotated above

counterregional glide plane G, creating a shelf break and locus of sediment

accumulation

accumulation landward of the outlying shale diapir. Fault H is initiated in

response to continued extension and mobile-shale withdrawal. Sediment loading

proximal to the diapir and subregional subsidence enhance shale withdrawal,

severing the subsurface glide plane G. Subregional withdrawal subsidence within

fault block G-H ceases. Sediments fill remaining accommodation space in the area

and prograde the shelf break eastward of fault H. Fault G continues to show

limited activity and growth well into time 2 (T2), but the bulk of extension and

growth between T1 and T2 is taken up at fault H. Rotation occurs at depth above

the more eastward counterregional glide plane H, and both the shelf break and

loci of

landward of the outlying shale diapir. Fault H is initiated in

response to continued extension and mobile-shale withdrawal. Sediment loading

proximal to the diapir and subregional subsidence enhance shale withdrawal,

severing the subsurface glide plane G. Subregional withdrawal subsidence within

fault block G-H ceases. Sediments fill remaining accommodation space in the area

and prograde the shelf break eastward of fault H. Fault G continues to show

limited activity and growth well into time 2 (T2), but the bulk of extension and

growth between T1 and T2 is taken up at fault H. Rotation occurs at depth above

the more eastward counterregional glide plane H, and both the shelf break and

loci of  accumulation

accumulation reside

reside  east

east of fault H and proximal of glide plane H (Figure

13c). Expansion and growth continue along the H fault (T3), stratigraphic

thicknesses increasing by shale withdrawal and counterregional rotation. The H

fault eventually proves unable to keep pace with further extension because of

exhaustion of mobile material at depth. Any remaining accommodation space is

filled and there is a progressive eastward shift of extension faulting,

shelf-slope break location, and lateral shale withdrawal.

of fault H and proximal of glide plane H (Figure

13c). Expansion and growth continue along the H fault (T3), stratigraphic

thicknesses increasing by shale withdrawal and counterregional rotation. The H

fault eventually proves unable to keep pace with further extension because of

exhaustion of mobile material at depth. Any remaining accommodation space is

filled and there is a progressive eastward shift of extension faulting,

shelf-slope break location, and lateral shale withdrawal.

Comparison with the Niger Delta

The relationship between structure and stratigraphy in the geologic evolution

of the Columbus Basin resembles that identified by Evamy et al. (1978) in the

Niger Delta (Figure 14). In the

Niger Delta  model

model , shale migration establishes a bathymetric high in front of

the progradational Niger shelf system, forming a break between paralic/deltaic

sedimentation, which has been trapped behind the bulge and slope/bathyal

sedimentation outboard of the bulge crest. Beds deposited behind the bulge show

progressive downward rotation and steepening of dip along a counterregional

glide plane associated with progressively basinward migration of the mobile

shale. Large growth faults develop landward in response to extension and mobile

shale withdrawal at depth.

, shale migration establishes a bathymetric high in front of

the progradational Niger shelf system, forming a break between paralic/deltaic

sedimentation, which has been trapped behind the bulge and slope/bathyal

sedimentation outboard of the bulge crest. Beds deposited behind the bulge show

progressive downward rotation and steepening of dip along a counterregional

glide plane associated with progressively basinward migration of the mobile

shale. Large growth faults develop landward in response to extension and mobile

shale withdrawal at depth.

Although similarities between the offshore Nigeria tectonostratigraphic

processes and those of Trinidad's Columbus Basin are obvious, a few notable

differences exist. The most obvious of these differences is the location of the

shelf-slope break with respect to the migrating shale bulge. In the Niger Delta

model

model , the break between shelfal water depths and slope/bathyal water depths

occurs at the crest of the shale bulge (Figure

14). This configuration limits distribution of deep-marine facies to the

distal side of the bulge, having little primary depositional dip across the

sedimentary shelf system, proximal to the bulge. In contrast, the Orinoco Delta

strata exhibit a distinct break from shelf to slope/bathyal water depths on the

proximal side of the shale bulge. The result is a significant bathymetry change

across the sedimentary shelf and slope systems. Slope and basinal facies are

thus able to downlap and onlap the underlying mobile shales. This difference

creates significant primary depositional dip across the Columbus Basin

depositional system proximal to the shale bulge.

, the break between shelfal water depths and slope/bathyal water depths

occurs at the crest of the shale bulge (Figure

14). This configuration limits distribution of deep-marine facies to the

distal side of the bulge, having little primary depositional dip across the

sedimentary shelf system, proximal to the bulge. In contrast, the Orinoco Delta

strata exhibit a distinct break from shelf to slope/bathyal water depths on the

proximal side of the shale bulge. The result is a significant bathymetry change

across the sedimentary shelf and slope systems. Slope and basinal facies are

thus able to downlap and onlap the underlying mobile shales. This difference