![]() Click

to view page images in PDF format.

Click

to view page images in PDF format.

Geochemical Characterization of Natural Gas: A Physical

Multivariable Approach and its Applications in Maturity and  Migration

Migration Estimates

Estimates

Alain Prinzhofer,1 Marcio Rocha Mello,2 and Tikae Takaki2

Search and Discovery Article #40016, 2001

Adapted for online presentation from article of the

same title by the same authors in AAPG Bulletin, v.. 84, no. 8 (August 2000), p.

1152-1172. This article is presented here together with article entitled

"Why Light Hydrocarbons Do Not Form A Gas Phase After Diffusing Through

Seals" (Search and Discovery # 40017, 2001) by Alton A. Brown as a forum

for discussion of hydrocarbon  migration

migration .

.

1Division of Geology-Geochemistry, Institut Francais du Petrole, 1 and 4 Avenue de Bois Preau, 92852 Rueil Malmaison Cedex, France; e-mail: [email protected]

2Petrobras Research and Development Center - Cenpes, Cidade Universitaria, Quadra 7, Ilha do Fundao, 21949-900, Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

Gas geochemistry has recently been shown to enhance

information regarding the geological history of hydrocarbons. In this paper,

graphical representations of physico-chemical processes affecting the chemical

and isotopic signatures of natural gases are exemplified. These diagrams are

based on experimental studies and the use of basic statistics to extract

significant and synthetic parameters from the geochemical data. From 11 chemical

and isotopic ratios, a statistical analysis (PCA) yields two very important

parameters. The first parameter, using mainly the C2+ fraction of the

gas, relates to maturity and the second parameter, involving the proportions and

d13C values of methane,

indicates mainly segregative  migration

migration . Positive values of the second parameter

indicate that gases accumulated far from their source, whereas negative values

correspond to residual gas pools after leakage of a part of the fluids. A

tentative reconstruction of the gas history has been performed in two Brazilian

basins: the Espirito Santo basin and part of the Reconcavo basin. The Espirito

Santo basin is located on the passive continental margin of the Atlantic Ocean,

and the Reconcavo basin corresponds to an intracontinental aborted rift. In both

cases, the source rocks are mainly lacustrine, with thermal maturities ranging

between the oil window and the beginning of the gas window. Results show that in

the Reconcavo basin, a major fault (the Mata Catu fault) acts as a drain for

hydrocarbon

. Positive values of the second parameter

indicate that gases accumulated far from their source, whereas negative values

correspond to residual gas pools after leakage of a part of the fluids. A

tentative reconstruction of the gas history has been performed in two Brazilian

basins: the Espirito Santo basin and part of the Reconcavo basin. The Espirito

Santo basin is located on the passive continental margin of the Atlantic Ocean,

and the Reconcavo basin corresponds to an intracontinental aborted rift. In both

cases, the source rocks are mainly lacustrine, with thermal maturities ranging

between the oil window and the beginning of the gas window. Results show that in

the Reconcavo basin, a major fault (the Mata Catu fault) acts as a drain for

hydrocarbon  migration

migration at the basin scale, associating a major isotopic

fractionation to the gas

at the basin scale, associating a major isotopic

fractionation to the gas  migration

migration with a clear correlation between isotope

fractionation and the distance of

with a clear correlation between isotope

fractionation and the distance of  migration

migration . In the Espirito Santo basin, this

segregation appears in the platform sediments to a lesser extent and is absent

in the gas pools located in the paleocanyons filled with turbidites. This

long-distance

. In the Espirito Santo basin, this

segregation appears in the platform sediments to a lesser extent and is absent

in the gas pools located in the paleocanyons filled with turbidites. This

long-distance  migration

migration in the platform sediments suggests that a hydrocarbon

kitchen is located offshore.

in the platform sediments suggests that a hydrocarbon

kitchen is located offshore.

![]() Figure 1--General

scheme of hydrocarbon gas history from its genesis to its sampling. In the

source rocks, three different gas steps of formation may be defined: gas

generation associated with the oil, late gas generation from the mature kerogen,

and secondary cracking of the oil remaining in the source rock. In the

reservoir, after expulsion and

Figure 1--General

scheme of hydrocarbon gas history from its genesis to its sampling. In the

source rocks, three different gas steps of formation may be defined: gas

generation associated with the oil, late gas generation from the mature kerogen,

and secondary cracking of the oil remaining in the source rock. In the

reservoir, after expulsion and  migration

migration , two other possible gas inputs may be

distinguished: secondary cracking of the reservoired oils and bacterial

contamination. Segregation due to transport may occur in the source rocks, in

the drains, and from the reservoir.

, two other possible gas inputs may be

distinguished: secondary cracking of the reservoired oils and bacterial

contamination. Segregation due to transport may occur in the source rocks, in

the drains, and from the reservoir.

Figure 6--Principle of

the Gastar diagram

with error bars, including the three main processes (maturity, segregative

Figure 6--Principle of

the Gastar diagram

with error bars, including the three main processes (maturity, segregative

migration

migration , efficiency of accumulation), their direction of variations, and how

each affects the 11 normalized geochemical parameters. Because of the

normalization through averaged values and standard deviations, Gastar diagram

axes have the same scales.

, efficiency of accumulation), their direction of variations, and how

each affects the 11 normalized geochemical parameters. Because of the

normalization through averaged values and standard deviations, Gastar diagram

axes have the same scales.

![]() Figure 8--Projection of

the 11 geochemical parameters on the first 2 Eigen vectors V1-V2 plane

corresponding to the most discriminant dimensions of the database. The first

Eigen vector, V1, is interpreted as a good representation of maturity; the

second Eigen vector, V2, may be assumed to indicate segregative

Figure 8--Projection of

the 11 geochemical parameters on the first 2 Eigen vectors V1-V2 plane

corresponding to the most discriminant dimensions of the database. The first

Eigen vector, V1, is interpreted as a good representation of maturity; the

second Eigen vector, V2, may be assumed to indicate segregative  migration

migration .

.

Figure 13--PCA

(principal components analysis) representation of gases from the Espirito Santo

basin. The gases located in the platform sediments show an oblique trend,

indicating fractionation during

Figure 13--PCA

(principal components analysis) representation of gases from the Espirito Santo

basin. The gases located in the platform sediments show an oblique trend,

indicating fractionation during  migration

migration , and the gases located in two

paleocanyons show two parallel horizontal trends, indicating only maturity

gradient with no evidence of segregation due to transport.

, and the gases located in two

paleocanyons show two parallel horizontal trends, indicating only maturity

gradient with no evidence of segregation due to transport.

Figure 14--Geological

cross sections through the Espirito Santo basin (after Estrella et al., 1984).

(a) Cross section through a paleocanyon filled with turbidite sediments showing

the short

Figure 14--Geological

cross sections through the Espirito Santo basin (after Estrella et al., 1984).

(a) Cross section through a paleocanyon filled with turbidite sediments showing

the short  migration

migration of hydrocarbons from the disconformity between the

lacustrine shales and turbidites into the reservoirs. (b) Cross section through

the platform sediments showing the long

of hydrocarbons from the disconformity between the

lacustrine shales and turbidites into the reservoirs. (b) Cross section through

the platform sediments showing the long  migration

migration distance and the direction of

filling from east to west.

distance and the direction of

filling from east to west.

Figure

15--Geographical location and simplified geological map of the Reconcavo basin.

Figure

15--Geographical location and simplified geological map of the Reconcavo basin.

Figure

16--Gastar diagram for data from the Reconcavo basin. (a) Gases located in

fields in a transection perpendicular to the Mata Catu fault with no evidence of

segregation due to

Figure

16--Gastar diagram for data from the Reconcavo basin. (a) Gases located in

fields in a transection perpendicular to the Mata Catu fault with no evidence of

segregation due to  migration

migration and showing only maturity gradient. (b) Gases

located along the Mata Catu fault with a clear scatter between maturity

parameters (right part of the diagram) and

and showing only maturity gradient. (b) Gases

located along the Mata Catu fault with a clear scatter between maturity

parameters (right part of the diagram) and  migration

migration parameters (left part of

the diagram). The scales are the same for all 11 axes of each Gastar diagram.

parameters (left part of

the diagram). The scales are the same for all 11 axes of each Gastar diagram.

Figure

17--PCA (principal component analysis) representation for gases from the

southern part of the Rec¶ncavo basin. The gases perpendicular to the Mata Catu

fault exhibit a pure maturity trend, whereas the gases along the fault show a

large range of variation in the V2 values indicating strong fractionation during

Figure

17--PCA (principal component analysis) representation for gases from the

southern part of the Rec¶ncavo basin. The gases perpendicular to the Mata Catu

fault exhibit a pure maturity trend, whereas the gases along the fault show a

large range of variation in the V2 values indicating strong fractionation during

migration

migration .

.

Physico-Chemical Processes in Gas History and Their Experimental Control

Defining a Set of Possible Parameters

Parameters Relating to Maturity

Parameters Relating to the Efficiency of Accumulation

Parameters

for the Segregation Processes During  Migration

Migration

A First Approach: The Gastar Diagram

Multicomponents analysis: Principle and Results

Geological Examples: The Link Among Physics, Statistics, and Geology

Gas geochemistry has become an increasingly sophisticated tool for understanding the geological history of hydrocarbons from their generation in source rocks to their accumulations in reservoirs. Interpretation of gas compositions is also an important factor in drilling operations because it is the foremost information used in mud logging. Because the complex history of gases is often difficult to decipher with the few chemical indicators that are available in routine gas analysis, an effort has been made for a better understanding of the chemistry and physics inducing the variability of gas compositions. For decades, the two main gas indicators were the wetness of the gas ([C2-C5]/[C1-C5]) and the carbon isotopic composition of methane, expressed in part per mil vs. the PDB standard. Source, thermal maturity, and possible bacterial contamination were evidenced from their respective variations (Stahl and Carey, 1975; Schoell, 1983; Mattavelli et al., 1983; Faber et al., 1992). The addition of other parameters, such as the d13C of ethane or propane (James, 1983; Faber, 1987; Clayton, 1991; Berner et al., 1992, 1995) and the hydrogen isotopic composition of methane (Schoell, 1980) or of ethane and propane (Barker and Pollock, 1984; Prinzhofer and Huc, 1995), was also suggested for a better characterization of the gas history; however, a systematic control on these parameters was only recently developed from experimental studies and associated modeling (Clayton, 1991; Berner et al., 1995; Lorant et al., 1998), although few available studies use the whole range of parameters (proportions of each compound, isomer ratio, isotopic value). An interpretation of the whole chemical and carbon isotopic gas data is thus very rarely completed. Hydrogen isotopic ratios are even less common and are probably often scattered by large uncertainties induced by sample preparation and measurements.

The development of new analytical tools, such as the GC-C-IRMS (gas chromatograph-combustion interface-isotopic ratio mass spectrometer), gives easy access to the whole set of d13C for the C1-C4 range and CO2. More conventional determinations of the chemical proportions are also possible for all molecules present, even in minor amounts in a gas sample using classical gas chromatography. In addition, new experimental studies of physical and chemical processes have been obtained to get the best information from all the chemical and isotopic parameters (Clayton, 1991; Berner et al., 1995; Prinzhofer and Pernaton, 1997; Prinzhofer and Lorant, 1997; Lorant et al., 1998). The recent increase in analytical and experimental information on gas chemistry and isotopic ratios, however, renders the interpretations more complex, largely because of the increasing amount of different kinds of data. We present here a new attempt to represent graphically the variability of gas compositions under the constraints of physico-chemical processes tested and calibrated on laboratory experiments. Simple statistical treatment of natural gas data provides a set of synthetic parameters involving both chemical and isotopic measurements. We chose to describe results of gas data using both star-diagrams applied to gas (Gastar diagrams) and principal components analysis to easily interpret the main characteristics in a series of natural gases. Some applications used in areas of Brazil are described to demonstrate the interest in this new approach for describing gas heterogeneities.

PHYSICO-CHEMICAL PROCESSES IN GAS HISTORY AND THEIR EXPERIMENTAL CONTROL

Genesis in the source rock, expulsion,  migration

migration ,

accumulation, alteration, and leakage are potential segregative processes

leading to specific gas chemical and isotopic evolutions varying from one

occurrence to another (Figure

1). Three possible origins may be envisaged for

thermogenic gases generated in the source rock (Clayton, 1991; Behar et al.,

1992): gas coming from the kerogen in association with the oil genesis (gas 1),

late gas generation from the kerogen after the first oil generation that is

mainly composed of methane (gas 2), and gas generated by the thermal degradation

of the oil or a part of the oil (generally the heavier compounds) remaining in

the source (gas 3). Although these gases are expelled from the source rock, a

part of them may remain adsorbed on the organic matter (Friedrich and Juntgen,

1972), inducing a first segregation process. Hydrocarbon

,

accumulation, alteration, and leakage are potential segregative processes

leading to specific gas chemical and isotopic evolutions varying from one

occurrence to another (Figure

1). Three possible origins may be envisaged for

thermogenic gases generated in the source rock (Clayton, 1991; Behar et al.,

1992): gas coming from the kerogen in association with the oil genesis (gas 1),

late gas generation from the kerogen after the first oil generation that is

mainly composed of methane (gas 2), and gas generated by the thermal degradation

of the oil or a part of the oil (generally the heavier compounds) remaining in

the source (gas 3). Although these gases are expelled from the source rock, a

part of them may remain adsorbed on the organic matter (Friedrich and Juntgen,

1972), inducing a first segregation process. Hydrocarbon  migration

migration from the

source rocks to the reservoirs through porous rocks forming the drains may also

induce different segregations due to transport, dispersion, and retention (Bondar,

1987). In the reservoir, a fourth hydrocarbon gas fraction may be found coming

from the in situ thermal decomposition of the oil (gas 4). The accumulated gas

mixture may be affected by segregative loss through the wall of the accumulation

(cap rocks or water contact) and may be contaminated by an influx of bacterial

gas if the reservoir is shallow enough.

from the

source rocks to the reservoirs through porous rocks forming the drains may also

induce different segregations due to transport, dispersion, and retention (Bondar,

1987). In the reservoir, a fourth hydrocarbon gas fraction may be found coming

from the in situ thermal decomposition of the oil (gas 4). The accumulated gas

mixture may be affected by segregative loss through the wall of the accumulation

(cap rocks or water contact) and may be contaminated by an influx of bacterial

gas if the reservoir is shallow enough.

The main problem with gas interpretation today is the outstanding number of unknowns that are greater than the commonly measurable number of data types. Looking at the hydrocarbon part of the gas C1-C4, nine independent parameters are available (chemical proportions normalized to 100%, i.e., four independent values and five carbon isotopic ratios). Several case studies, in fact, have dealt with the origins and accumulation occurrence of natural gas using these nine parameters. James (1983, 1990) suggested using the carbon isotopic difference between each gas hydrocarbon to determine an equivalent maturity of its source rocks. The carbon isotopic ratio of methane, enriched in 13C when maturity increases, has been calibrated through various works in terms of thermal stress (Franck et al., 1974; Chung and Sackett, 1979; Schoell, 1983). The C2-C4 carbon isotopic information (any d13C becomes less negative with increasing maturity), regardless of association with the methane isotopic information, has also been used and modeled for the purpose of characterizing the transformation ratio of the gas source (Galimov, 1975; Faber, 1987; Clayton, 1991; Rooney et al., 1995; Berner et al., 1995; Prinzhofer and Huc, 1995; Prinzhofer and Lorant, 1997; Lorant et al., 1998). The modeling of the isotope fractionation was done assuming thermodynamic equilibrium (James, 1983; Galimov, 1975) or a purely kinetic control (Clayton, 1991; Berner et al., 1995; Rooney et al., 1995; Lorant et al., 1998). Although these approaches give coherent qualitative behaviors, no reliable quantification of the maturity of gases can be claimed.

Because different natural (Colombo et al., 1970, Friedrich

and Juntgen, 1972; Prinzhofer and Pernaton, 1997) and experimental (Hoering and

Moore, 1958; Galimov, 1975; Pernaton et al., 1996; Krooss et al., 1998) evidence

has suggested that methane could be affected by several secondary changes in its

chemical proportion and in its isotopic ratios (bacterial contamination,

segregative  migration

migration ), after Prinzhofer and Huc (1995), Prinzhofer and Lorant

(1997), and Lorant et al. (1998), we suggest using mainly the C2+

fraction to characterize the genetic processes. Using both the chemical and

isotopic proportions of ethane and propane, Lorant et al. (1998) pointed out the

importance of another variable, the degree of opening of the system. This

variable characterizes two distinct phenomena: the ability of generated

molecules to react and transform themselves after being generated (as secondary

thermal alteration), and the fact that the gas present today in a reservoir may

correspond to an intermediate between the lately generated gas and the sum of

the whole gas generated from the beginning of the oil window to the present. The

first attempt to describe the dynamics of gas accumulation in a semiopen system

was made by Galimov (1988) and Rooney et al. (1995). They described a semiopen

accumulation in a reservoir, whereas Lorant et al. (1998) described the

residence time of gases in the source rocks. For this purpose, Lorant et al.

modeled the possible trend of maturation in a d13C2-d13C3

vs. C2/C3 diagram, as was suggested by Prinzhofer and Huc

(1995) with natural gas series. In the Y-axis, the difference of d13C

is

), after Prinzhofer and Huc (1995), Prinzhofer and Lorant

(1997), and Lorant et al. (1998), we suggest using mainly the C2+

fraction to characterize the genetic processes. Using both the chemical and

isotopic proportions of ethane and propane, Lorant et al. (1998) pointed out the

importance of another variable, the degree of opening of the system. This

variable characterizes two distinct phenomena: the ability of generated

molecules to react and transform themselves after being generated (as secondary

thermal alteration), and the fact that the gas present today in a reservoir may

correspond to an intermediate between the lately generated gas and the sum of

the whole gas generated from the beginning of the oil window to the present. The

first attempt to describe the dynamics of gas accumulation in a semiopen system

was made by Galimov (1988) and Rooney et al. (1995). They described a semiopen

accumulation in a reservoir, whereas Lorant et al. (1998) described the

residence time of gases in the source rocks. For this purpose, Lorant et al.

modeled the possible trend of maturation in a d13C2-d13C3

vs. C2/C3 diagram, as was suggested by Prinzhofer and Huc

(1995) with natural gas series. In the Y-axis, the difference of d13C

is  plotted

plotted between two molecules (which reduces source heterogeneities effects

to a second-order

between two molecules (which reduces source heterogeneities effects

to a second-order  effect

effect ) vs. the ratio C2/C3 for the

X-axis, thus avoiding the problem of the normalization to 100% of all individual

gas molecules. A mathematical modeling, based on closed-system pyrolysis

experiment data, outlines different areas of genesis for given thermal

conditions (Figure 2) corresponding to the main zone of primary cracking of

kerogen, the secondary cracking of heavy oil compounds (NSO heteroatomic

molecules), or the hydrocarbon part of the oils cracking, up to later stages of

thermal degradation corresponding to the secondary cracking of the C2+

fraction of the gas. The maturity is correlated to vitrinite reflectance as an

index. The degree of opening of the system, equivalent to the residence time of

the gas, may be deduced qualitatively from the positions of gas signatures

between the open-system and the closed-system trends. Closed-system pyrolysis

experiments have also shown that the butane isomers evolve with an increase in

(1) the iC4/nC4 ratio, (2) the 13C proportion

of each compound, and (3) the isotopic difference between nC4 and iC4

with maturation (Figure 3).

) vs. the ratio C2/C3 for the

X-axis, thus avoiding the problem of the normalization to 100% of all individual

gas molecules. A mathematical modeling, based on closed-system pyrolysis

experiment data, outlines different areas of genesis for given thermal

conditions (Figure 2) corresponding to the main zone of primary cracking of

kerogen, the secondary cracking of heavy oil compounds (NSO heteroatomic

molecules), or the hydrocarbon part of the oils cracking, up to later stages of

thermal degradation corresponding to the secondary cracking of the C2+

fraction of the gas. The maturity is correlated to vitrinite reflectance as an

index. The degree of opening of the system, equivalent to the residence time of

the gas, may be deduced qualitatively from the positions of gas signatures

between the open-system and the closed-system trends. Closed-system pyrolysis

experiments have also shown that the butane isomers evolve with an increase in

(1) the iC4/nC4 ratio, (2) the 13C proportion

of each compound, and (3) the isotopic difference between nC4 and iC4

with maturation (Figure 3).

The C2+ gas fraction holds information on the

genesis of hydrocarbons. The isotopic signature of methane, however,

distinguishes segregation processes during the  migration

migration from a possible

contamination by bacterial gas or from a simple maturity trend. A C2/C1

diagram vs. the d13C of

methane makes it possible to distinguish these three possible trends (Prinzhofer

and Pernaton, 1997): (1) a straight line when

from a possible

contamination by bacterial gas or from a simple maturity trend. A C2/C1

diagram vs. the d13C of

methane makes it possible to distinguish these three possible trends (Prinzhofer

and Pernaton, 1997): (1) a straight line when  plotted

plotted in normal scales,

characteristic of a mixing trend between two end members (for example

thermogenic and bacterial end-members) and (2) a diffusive fractionating

in normal scales,

characteristic of a mixing trend between two end members (for example

thermogenic and bacterial end-members) and (2) a diffusive fractionating

migration

migration would show a concave-shaped curve (Figure

4a). In a semilogarithmic

scale (Figure 4b), diffusive fractionation trends plot straight lines, whereas

mixing trends make convex curves. (3) The slope is always reversed to both

bacterial mixing and diffusive fractionation in a simple maturity trend (Figure

4). The whole subject of gas segregation, in fact, revives the debate about the

existence or the importance of isotopic and chemical fractionation during

would show a concave-shaped curve (Figure

4a). In a semilogarithmic

scale (Figure 4b), diffusive fractionation trends plot straight lines, whereas

mixing trends make convex curves. (3) The slope is always reversed to both

bacterial mixing and diffusive fractionation in a simple maturity trend (Figure

4). The whole subject of gas segregation, in fact, revives the debate about the

existence or the importance of isotopic and chemical fractionation during

migration

migration (Colombo et al., 1965, 1966, 1970; Neglia, 1979; Fuex, 1980; Reitsema

et al., 1981; Ricchiuto and Schoell, 1988; Pernaton et al, 1996; Prinzhofer and

Pernaton, 1997). One of the major arguments opposing this concept views the gas

transport through buoyancy as a process without chemical or isotopic

fractionation. Fractionation may happen only conjunctively with diffusion and

adsorption. The relative importance of these two processes, however, is still

not fully understood. Adsorption is a very poorly known process in terms of

quantitative importance except in coal layers, where chemical and isotopic

fractionations have been proven (Colombo et al., 1970; Friedrich and Juntgen,

1972). Diffusion in a gas phase or in dry rocks introduces significant

fractionation (Pernaton et al., 1996), but its time scale seems very short

compared to geological time. This rapid process, in fact, would induce a

quasi-immediate equilibrium at the geological scale without any remaining

fractionation. Diffusion of some gas molecules when they are dissolved in water

(mainly methane, for which the solubility may be large at high pressures) is

another realistic way of having an isotopic fractionation (Pernaton et al.,

1996); however, in this case, the duration of the process is also debated when

compared to reasonable geological time scales. Some workers argue that, contrary

to the previous case of gas diffusion, the duration of the process may be too

long compared to geological time (Krooss et al., 1992), whereas other workers

would consider that this process of solubilization/diffusion is very efficient

for secondary gas

(Colombo et al., 1965, 1966, 1970; Neglia, 1979; Fuex, 1980; Reitsema

et al., 1981; Ricchiuto and Schoell, 1988; Pernaton et al, 1996; Prinzhofer and

Pernaton, 1997). One of the major arguments opposing this concept views the gas

transport through buoyancy as a process without chemical or isotopic

fractionation. Fractionation may happen only conjunctively with diffusion and

adsorption. The relative importance of these two processes, however, is still

not fully understood. Adsorption is a very poorly known process in terms of

quantitative importance except in coal layers, where chemical and isotopic

fractionations have been proven (Colombo et al., 1970; Friedrich and Juntgen,

1972). Diffusion in a gas phase or in dry rocks introduces significant

fractionation (Pernaton et al., 1996), but its time scale seems very short

compared to geological time. This rapid process, in fact, would induce a

quasi-immediate equilibrium at the geological scale without any remaining

fractionation. Diffusion of some gas molecules when they are dissolved in water

(mainly methane, for which the solubility may be large at high pressures) is

another realistic way of having an isotopic fractionation (Pernaton et al.,

1996); however, in this case, the duration of the process is also debated when

compared to reasonable geological time scales. Some workers argue that, contrary

to the previous case of gas diffusion, the duration of the process may be too

long compared to geological time (Krooss et al., 1992), whereas other workers

would consider that this process of solubilization/diffusion is very efficient

for secondary gas  migration

migration (Nelson and Simmons, 1992, 1995; Prinzhofer et al.,

1995; Schneider et al., 1995). In addition, diffusion may be considered as a

dispersive phenomenon rendering the concept of a new accumulation of a gas pool

difficult to conceive. Our objective in this paper is to present how an

effective transport process involving fractionation through diffusion in water

can occur together with a new accumulation partially generated with this

process. Figure 5 shows the profile of fluid pressure through a lithostatic

sedimentary column disrupted with a gas pool. The pressure gradient through the

gas leg is steeper due to the low density of gas compared to water. An

overpressure due to buoyancy exists at the interface between the gas leg and the

seal, and the gas leg is stable if the capillary pressure (or entrance pressure)

of the seal is equal or greater than the overpressure due to the gas leg.

Whatever the entrance pressure, however, the overpressure locally increases the

solubilization of the gas compounds in the water of the seal. The solubilized

gas then diffuses through the water network of the seal. As the fluid pressure

decreases through the seal to reach the hydrostatic pressure, the diffusion of

dissolved gas, within a very short distance, will crosscut its saturation curve

in water because this saturation will decrease as a function of the pressure.

Gas molecules will then generate yet another gas phase, which is capable of

moving through buoyancy without any fractionation. At a macroscopic scale, we

see a gas flux through the cap rocks, which may be modeled by an ad hoc low

relative permeability. The actual physical process observed, in fact, will be a

very local solubilization/desolubilization of gas through the water at the lower

end of cap rocks (this may be at the centimeter scale), giving the same

macroscopic gas flux but inducing both chemical and isotopic fractionation. This

fractionation will occur only at the point where the gas is dissolved in the

water.

(Nelson and Simmons, 1992, 1995; Prinzhofer et al.,

1995; Schneider et al., 1995). In addition, diffusion may be considered as a

dispersive phenomenon rendering the concept of a new accumulation of a gas pool

difficult to conceive. Our objective in this paper is to present how an

effective transport process involving fractionation through diffusion in water

can occur together with a new accumulation partially generated with this

process. Figure 5 shows the profile of fluid pressure through a lithostatic

sedimentary column disrupted with a gas pool. The pressure gradient through the

gas leg is steeper due to the low density of gas compared to water. An

overpressure due to buoyancy exists at the interface between the gas leg and the

seal, and the gas leg is stable if the capillary pressure (or entrance pressure)

of the seal is equal or greater than the overpressure due to the gas leg.

Whatever the entrance pressure, however, the overpressure locally increases the

solubilization of the gas compounds in the water of the seal. The solubilized

gas then diffuses through the water network of the seal. As the fluid pressure

decreases through the seal to reach the hydrostatic pressure, the diffusion of

dissolved gas, within a very short distance, will crosscut its saturation curve

in water because this saturation will decrease as a function of the pressure.

Gas molecules will then generate yet another gas phase, which is capable of

moving through buoyancy without any fractionation. At a macroscopic scale, we

see a gas flux through the cap rocks, which may be modeled by an ad hoc low

relative permeability. The actual physical process observed, in fact, will be a

very local solubilization/desolubilization of gas through the water at the lower

end of cap rocks (this may be at the centimeter scale), giving the same

macroscopic gas flux but inducing both chemical and isotopic fractionation. This

fractionation will occur only at the point where the gas is dissolved in the

water.

Because these new diagrams do not represent the whole information obtainable from a gas sample and never fully quantify all parameters involved in the gas history, in the attempt to get more reliable information on the different factors influencing the gas compositions, we propose to increase the number of physically significant geochemical data for natural gas. Our main suggestion is to quantify the maturity and the migrating fractionation and to tentatively estimate the yield of accumulation (or the degree of opening).

After defining a set of informative data, we present some statistical treatments that can then be applied to different case studies.

DEFINING A SET OF POSSIBLE PARAMETERS

The first issue to resolve is the choice of geochemical

parameters evolving in a well-characterized (if not monotonous) way for the

three main defined processes (maturity, efficiency of accumulation, and degree

of segregation). The most appropriate set of parameters has been taken from

experimental data for which the maturity conditions are well controlled, and for

which we can consider that no other phenomena are superimposed; however, the

problem of direct extrapolation of pyrolysis experiments (high temperatures,

short durations) to geological conditions (lower temperatures and long-term

scales) always reduces the possibility of quantitative extrapolation to natural

case studies. For this reason, we do not present any quantitative values for

maturity, efficiency of accumulation, or distance of  migration

migration .

.

Parameters Relating to Maturity

Gases become enriched in methane with increasing thermal

maturity (Stahl and Carey, 1975; Stahl, 1977; Chung and Sackett, 1979); however,

other phenomena (bacterial contamination, segregative  migration

migration ) may affect the

dryness of the gases. Instead of using the dryness of the gases, which

corresponds to a mathematically relatively complex expression (C1/C1

- C5), we use the simple ratio C1/C2,

which gives equivalent information and is easily correlated with the other

chemical ratios, such as C2/C3 or iC4/nC4.

The carbon isotopic signatures of individual hydrocarbons, such as methane,

ethane, and propane, become isotopically heavier with increasing maturity (Chung

and Sackett, 1979; Chung et al., 1988). From their experimental work, Lorant et

al. (1998) showed that the difference of d13C

between methane and ethane, and between ethane and propane, increases with

maturity, at least for gas generation behaving as a relatively confined system.

Arneth and Matzigkeit (1985) and Faber (1987) already described this kind of

divergence of the d13C with

maturity. Experimental and natural examples presented evidence that the C2/C3

ratio increased with maturity (Prinzhofer and Huc, 1995). Several other

parameters involving the two butane isomers having a nonambiguous link with

maturity were observed (Figure

3): the ratio iC4/nC4 and

the two carbon isotopic ratios d13iC4

and d13nC4, as

well as the isotopic difference between these two values, are positively

correlated with maturity. In short, we may define 11 geochemical parameters, all

of which are linked positively with maturity: C1/C2, C2/C3,

iC4/nC4, d13C1,

d13C2, d13C3,

d13iC4, d13nC4,

d13C2-d13C1,

d13C3-d13C2,

and d13nC4-d13iC4.

Clearly, other processes, such as biodegradation, bacterial contamination, or

segregative

) may affect the

dryness of the gases. Instead of using the dryness of the gases, which

corresponds to a mathematically relatively complex expression (C1/C1

- C5), we use the simple ratio C1/C2,

which gives equivalent information and is easily correlated with the other

chemical ratios, such as C2/C3 or iC4/nC4.

The carbon isotopic signatures of individual hydrocarbons, such as methane,

ethane, and propane, become isotopically heavier with increasing maturity (Chung

and Sackett, 1979; Chung et al., 1988). From their experimental work, Lorant et

al. (1998) showed that the difference of d13C

between methane and ethane, and between ethane and propane, increases with

maturity, at least for gas generation behaving as a relatively confined system.

Arneth and Matzigkeit (1985) and Faber (1987) already described this kind of

divergence of the d13C with

maturity. Experimental and natural examples presented evidence that the C2/C3

ratio increased with maturity (Prinzhofer and Huc, 1995). Several other

parameters involving the two butane isomers having a nonambiguous link with

maturity were observed (Figure

3): the ratio iC4/nC4 and

the two carbon isotopic ratios d13iC4

and d13nC4, as

well as the isotopic difference between these two values, are positively

correlated with maturity. In short, we may define 11 geochemical parameters, all

of which are linked positively with maturity: C1/C2, C2/C3,

iC4/nC4, d13C1,

d13C2, d13C3,

d13iC4, d13nC4,

d13C2-d13C1,

d13C3-d13C2,

and d13nC4-d13iC4.

Clearly, other processes, such as biodegradation, bacterial contamination, or

segregative  migration

migration , may affect to some degree a number of these parameters.

, may affect to some degree a number of these parameters.

Parameters Relating to the Efficiency of Accumulation

It has been observed (Lorant et al., 1998) that the difference of d13C between two consecutive components (d13C1-d13C2 and d13C2-d13C3) exhibits greater fractionation for a completely closed system (total accumulation of gas and possibility of secondary thermal alteration) than for an open system (isolation of the produced molecules from their source). The same kind of divergence is observed between the d13C of iC4 and nC4 in confined-system pyrolysis with values much higher than the source (Figure 3). Because this can be interpreted only as the result of secondary degradation of the two butane isomers, an open-system pyrolysis will give d13C trends without this secondary degradation inducing the observed divergence; therefore, 3 of the 11 previously defined parameters, d13C1-d13C2, d13C2-d13C3, and d13nC4-d13iC4, are interpreted as positively correlated with the efficiency of accumulation, as well as being correlated positively with maturity.

Parameters for the Segregation Processes During

Migration

Migration

Segregative  migration

migration may affect the parameters involving

methane (Galimov, 1975; Syngayevsky et al., 1978; Bondar, 1987; Pernaton et al.,

1996) both chemically and isotopically with negligible fractionation for heavier

hydrocarbons (Pernaton et al., 1996). Considering a gas system migrating through

porous rocks with a part of it migrating through solubilization/diffusion in

water, the migrating part of the gas will be enriched in methane, and this

methane will be enriched in 12C (Galimov, 1975; Pernaton et al.,

1996; Prinzhofer and Pernaton, 1997). Taking this into account, we can then say

that d13C1, d13C2-d13C1,

and C1/C2 may be strongly affected by

may affect the parameters involving

methane (Galimov, 1975; Syngayevsky et al., 1978; Bondar, 1987; Pernaton et al.,

1996) both chemically and isotopically with negligible fractionation for heavier

hydrocarbons (Pernaton et al., 1996). Considering a gas system migrating through

porous rocks with a part of it migrating through solubilization/diffusion in

water, the migrating part of the gas will be enriched in methane, and this

methane will be enriched in 12C (Galimov, 1975; Pernaton et al.,

1996; Prinzhofer and Pernaton, 1997). Taking this into account, we can then say

that d13C1, d13C2-d13C1,

and C1/C2 may be strongly affected by  migration

migration . As a

result, the distance of

. As a

result, the distance of  migration

migration will be negatively correlated with the first

of these three parameters, and positively correlated with the last two. As for

the parameters correlated with the efficiency of accumulation, these three

parameters are evidently also linked with both the thermal maturity and the

segregation during transport.

will be negatively correlated with the first

of these three parameters, and positively correlated with the last two. As for

the parameters correlated with the efficiency of accumulation, these three

parameters are evidently also linked with both the thermal maturity and the

segregation during transport.

A FIRST APPROACH: THE GASTAR DIAGRAM

We have defined and discussed 11 geochemical parameters (C2/C1,

C2/C3, iC4/nC4, d13C1,

d13C2, d13C3,

d13iC4, d13nC4,

d13C2-d13C3,

d13nC4-d13iC4,

and d13C2-d13C1),

all positively correlated with maturity, three of them linked with the

efficiency of accumulation (the three isotopic ratios differences), and three

linked with the distance of  migration

migration (the three last parameters, involving

methane). We decided to adapt for gas analyses a gas star diagram as commonly

used for the C6-C18 fraction for oil fingerprinting

(Kaufman et al., 1990; Magnier and Huc, 1995). Because carbon isotopic ratios of

methane range between about 50 and 60 delta-units, and whereas the iC4/nC4

ratio will show a variation of only one unit, it is imperative for gas analyses

to be normalized. To normalize all of these different values (chemical and

isotopic, with very different ranges of variations), we chose the following

normalization:

(the three last parameters, involving

methane). We decided to adapt for gas analyses a gas star diagram as commonly

used for the C6-C18 fraction for oil fingerprinting

(Kaufman et al., 1990; Magnier and Huc, 1995). Because carbon isotopic ratios of

methane range between about 50 and 60 delta-units, and whereas the iC4/nC4

ratio will show a variation of only one unit, it is imperative for gas analyses

to be normalized. To normalize all of these different values (chemical and

isotopic, with very different ranges of variations), we chose the following

normalization:

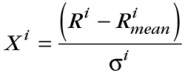

where Ri is the absolute value for the parameter i (chemical or isotopic ratio), is a mean value for the parameter i calculated from a general gas database, si is the standard deviation of parameter i within the same database, and Xi is the normalized value for the parameter i.

We used for this normalization a set of 289 gas

analyses, each of them with all chemical proportions from methane to

normal-butane, and all the C1-C4 carbon isotopic ratios.

The  locations

locations of the samples are diverse, from the North Sea, Bolivia, Brazil,

and Thailand. Table 1 gives the minimum and maximum values for both chemical and

isotopic signatures of these gases for each of the different geographical

of the samples are diverse, from the North Sea, Bolivia, Brazil,

and Thailand. Table 1 gives the minimum and maximum values for both chemical and

isotopic signatures of these gases for each of the different geographical

locations

locations . The average values and the standard deviations for the defined

geochemical parameters are also given for the whole set of data.

. The average values and the standard deviations for the defined

geochemical parameters are also given for the whole set of data.

The parameters were classified according to their

behavior vs. the three defined parameters (maturity, efficiency of accumulation,

and segregative  migration

migration ). Figure 6 gives the basic principle of the star

diagram (GASTAR diagram), exhibiting the monotonous variations of the 11

parameters with maturity and the direction of variation for some of the

parameters with the efficiency of accumulation and the segregative

). Figure 6 gives the basic principle of the star

diagram (GASTAR diagram), exhibiting the monotonous variations of the 11

parameters with maturity and the direction of variation for some of the

parameters with the efficiency of accumulation and the segregative  migration

migration . In

the same diagram, the assumed analytical uncertainties for each parameter are

represented. The star diagram for gases presented here, built on experimental

constraints, allows us to distinguish different gases and to interpret the

physico-chemical processes that affected the analyzed gas. The more usual star

diagrams used for the C6+ part of oils are only a descriptive way of

distinguishing oil heterogeneities through different fingerprinting.

. In

the same diagram, the assumed analytical uncertainties for each parameter are

represented. The star diagram for gases presented here, built on experimental

constraints, allows us to distinguish different gases and to interpret the

physico-chemical processes that affected the analyzed gas. The more usual star

diagrams used for the C6+ part of oils are only a descriptive way of

distinguishing oil heterogeneities through different fingerprinting.

Figure 7 shows two examples of data

(Table 2)  plotted

plotted in this diagram. Figure 7a presents a series of natural gases coming from a

multilayered reservoired field with a regular variation in maturity, with gas I

and gas V being the less and the more mature, respectively; however, a slight

disturbance interpreted as segregation during

in this diagram. Figure 7a presents a series of natural gases coming from a

multilayered reservoired field with a regular variation in maturity, with gas I

and gas V being the less and the more mature, respectively; however, a slight

disturbance interpreted as segregation during  migration

migration may be seen. Gas II, for

example, has a heavier d13C

of methane than every other gas, although it is one of the less mature. Thus,

gas II looks similar to a residual gas after segregative leakage. Figure 7b

corresponds to other gases from another multilayered field and shows different

behaviors; no segregative fractionation can be noticed, but gas III seems to

come from a reservoir with a better efficiency of accumulation than gases I and

II. It seems then possible to build constraints on the quality of the

accumulation induced by both the quality of the seal and the timing of gas

generation.

may be seen. Gas II, for

example, has a heavier d13C

of methane than every other gas, although it is one of the less mature. Thus,

gas II looks similar to a residual gas after segregative leakage. Figure 7b

corresponds to other gases from another multilayered field and shows different

behaviors; no segregative fractionation can be noticed, but gas III seems to

come from a reservoir with a better efficiency of accumulation than gases I and

II. It seems then possible to build constraints on the quality of the

accumulation induced by both the quality of the seal and the timing of gas

generation.

MULTICOMPONENTS ANALYSIS: PRINCIPLE AND RESULTS

The Gastar diagrams should not be used when a

large number of gas samples is available because the diagrams become

overcharged. Another practical technique uses multicomponent analysis or

principal components analysis (PCA). This mathematical statistical data

processing allows one to represent a complex multidimensional database in the

best chosen two-dimensional projection, as in, for example, a plane defined by

the two largest spread dimensions of information from the cloud of initial data

plotted

plotted in a hyperspace. The two principal vectors defining this plane are the

first two Eigen vectors (Debart et al., 1984). With our gas database of 289

natural samples, we created a PCA with the 11 different normalized geochemical

parameters by using the software Datadesk 4.1©. The projection of

the Eigen vectors on the 11 primitive axes and the weight of each vector are

presented in Table 3.

in a hyperspace. The two principal vectors defining this plane are the

first two Eigen vectors (Debart et al., 1984). With our gas database of 289

natural samples, we created a PCA with the 11 different normalized geochemical

parameters by using the software Datadesk 4.1©. The projection of

the Eigen vectors on the 11 primitive axes and the weight of each vector are

presented in Table 3.

In looking at the composition of the first vector V1, we see that all 11 geochemical parameters are linked to it with a same positive sign (Figure 8). This point is interpreted as a positive link of all these 11 parameters with maturity; moreover, the relative importance of each geochemical parameter on the V1 vector concerns substantially the parameters using C2+ information with a lesser importance for parameters involving methane. This poor correlation between methane and the C2+ fraction is visible on Figure 9 for the isotopic ratios of all the C1-C4 compounds; furthermore, the covariances between C2, C3, nC4, and iC4 are relatively stable and in the same range, whereas methane is definitely not correlated with anything except itself. We conclude from this statistical treatment that the C2+ fraction is more efficient than methane to characterize maturity, and that the first Eigen vector defined in this study is a good qualitative indicator of maturity.

Likewise, when focusing on the projection of the 11

primary geochemical parameters onto the V2 axis (Figure

8, Table 3), the weight

of all the C2+ parameters is much less than on the V1 axis. The

parameters involving methane information, however, are mainly projected onto the

V2 axis, and their directions are contrary to the horizontal axis. This is a

clear indication that the V2 vector cannot be linked with maturity (d13C1,

C1/C2, and d13C2-d13C1

should be on the same side of the V2 axis). V2 appears to be consistent with a

fractionation due to  migration

migration because the migrating gas would be isotopically

lighter in methane, only slightly affected by C2+ fractionation, and

enriched in methane in comparison with C2+. A residual gas would

exhibit opposite behavior. In conclusion, we assume that the second Eigen vector

V2 is mainly controlled by migrative fractionations.

because the migrating gas would be isotopically

lighter in methane, only slightly affected by C2+ fractionation, and

enriched in methane in comparison with C2+. A residual gas would

exhibit opposite behavior. In conclusion, we assume that the second Eigen vector

V2 is mainly controlled by migrative fractionations.

We should stress that this purely statistical

treatment applied to natural data gives an excellent qualitative consistency

with the independent assessments obtained from the physico-chemical

interpretations of laboratory experiments. In this statistical approach, a

mathematical calculation, insensitive to any physical constraints and set only

on natural gas data, gives the same results as the experimental evidence. To

illustrate this point, Figure 10 represents a series of laboratory pyrolyses

with increasing maturity in a diagram V1-V2, obtained from dry-confined

pyrolysis of a type II kerogen (Mesnil sur Vair, France). The trend defined is

almost parallel to the V1 axis, with a slightly negative slope. A trend of

experimental diffusive  migration

migration has been

has been  plotted

plotted in the same figure, assuming

that the C2+ part of the gas is not affected by any segregation when

the methane portion suffers a chemical and isotopic fractionation in accordance

with the experiments described in Pernaton et al. (1996). The trend

is mainly controlled by the V2 vector with a positive slope, with V2 being

positively correlated with the importance of

in the same figure, assuming

that the C2+ part of the gas is not affected by any segregation when

the methane portion suffers a chemical and isotopic fractionation in accordance

with the experiments described in Pernaton et al. (1996). The trend

is mainly controlled by the V2 vector with a positive slope, with V2 being

positively correlated with the importance of  migration

migration . This consistency of both

the statistics and the definition of maturity and segregative processes in gas

history urges us to test this new approach for interpreting geochemical gas data

on some concrete examples.

. This consistency of both

the statistics and the definition of maturity and segregative processes in gas

history urges us to test this new approach for interpreting geochemical gas data

on some concrete examples.

Considering that in some gas databases, the information on the two isomers of butane may be missing either their isotopic values or their molecular proportions, we also calculated the first two Eigen vectors of our database without the butane isotopic constraint (Table 4), and without both the proportions and the isotopic ratios of butane (Table 4). The results show the same tendency as with the whole C1-C4 database, and the values presented in Table 4 may be interpreted in the same way.

GEOLOGICAL EXAMPLES: THE LINK AMONG PHYSICS, STATISTICS, AND GEOLOGY

In two geological well-constrained examples,

we show how geochemical gas data representations give new information about the

overall gas history of a basin (maturation and  migration

migration ). The first example is

a portion of the Espirito Santo basin in Brazil. The stratigraphic and tectonic

style of this basin reflects the evolution of a mature, passive, rifted

continental margin of the south Atlantic Ocean (Estrella et al., 1984).

Basically, the Cretaceous marine stage is characterized by Albian-Cenomanian

platform sediments consisting of layers of sandstones and shales and eroded in

several places by large paleocanyons that were filled by Upper Cretaceous

turbidites (Trindade, 1987). The source rock is mainly present in the lacustrine

shales of the rift phase. Hydrocarbon fields occur in both platform and

turbidites sediments (Figure

11). It is possible to distinguish two contrasting

behaviors between these two geological settings for the reservoirs with the

Gastar diagram and with the PCA (Table

5). Figure 12 shows two Gastar diagrams

in turbidites and platform sediments, respectively, with three different fields

in each location. Figure 13 represents the entire range of analyzed gases in

these areas on the V1-V2 PCA diagram. Only the turbidite fields (paleocanyons 1

and 2) exhibit a gradient of maturity with negligible

). The first example is

a portion of the Espirito Santo basin in Brazil. The stratigraphic and tectonic

style of this basin reflects the evolution of a mature, passive, rifted

continental margin of the south Atlantic Ocean (Estrella et al., 1984).

Basically, the Cretaceous marine stage is characterized by Albian-Cenomanian

platform sediments consisting of layers of sandstones and shales and eroded in

several places by large paleocanyons that were filled by Upper Cretaceous

turbidites (Trindade, 1987). The source rock is mainly present in the lacustrine

shales of the rift phase. Hydrocarbon fields occur in both platform and

turbidites sediments (Figure

11). It is possible to distinguish two contrasting

behaviors between these two geological settings for the reservoirs with the

Gastar diagram and with the PCA (Table

5). Figure 12 shows two Gastar diagrams

in turbidites and platform sediments, respectively, with three different fields

in each location. Figure 13 represents the entire range of analyzed gases in

these areas on the V1-V2 PCA diagram. Only the turbidite fields (paleocanyons 1

and 2) exhibit a gradient of maturity with negligible  migration

migration

effect

effect , whereas

the platform fields show both maturity and

, whereas

the platform fields show both maturity and  migration

migration fractionations. This can be

seen from the Gastar diagrams, where a strong unconformity is seen between the

left and the right parts of the diagram for the platform fields because the

fingerprints of the turbidite fields are much more regular on the left side.

This is geologically in agreement with the fact that the hydrocarbon kitchens

for the turbidite sediments are proposed to be close to the disconformity

between the source rocks and the paleocanyon with a very short distance of

fractionations. This can be

seen from the Gastar diagrams, where a strong unconformity is seen between the

left and the right parts of the diagram for the platform fields because the

fingerprints of the turbidite fields are much more regular on the left side.

This is geologically in agreement with the fact that the hydrocarbon kitchens

for the turbidite sediments are proposed to be close to the disconformity

between the source rocks and the paleocanyon with a very short distance of

migration

migration (Figure 14a) and with small barriers of permeabilities (the turbidites

allowing gas transport mainly in a homogeneous Darcean flux). Indeed, Estrella

et al. (1984) characterized the rift hydrocarbon pods just below the

paleocanyons in such a way that the source beds are in direct contact through

the walls of the canyons with the turbidite reservoirs. The widespread,

coalescent turbidite bodies acted as hydrocarbon collectors in the bottom of the

canyons, allowing updip short secondary

(Figure 14a) and with small barriers of permeabilities (the turbidites

allowing gas transport mainly in a homogeneous Darcean flux). Indeed, Estrella

et al. (1984) characterized the rift hydrocarbon pods just below the

paleocanyons in such a way that the source beds are in direct contact through

the walls of the canyons with the turbidite reservoirs. The widespread,

coalescent turbidite bodies acted as hydrocarbon collectors in the bottom of the

canyons, allowing updip short secondary  migration

migration to occur (Figure

14a). The

hydrocarbon kitchen for the platform fields, however, is more remote in the

eastern part of the basin in the offshore area (Figure

14b). It is assumed that

the gases have had to cross a greater amount of low-porosity rocks before

filling the reservoirs. It is also worth mentioning that a direction of

to occur (Figure

14a). The

hydrocarbon kitchen for the platform fields, however, is more remote in the

eastern part of the basin in the offshore area (Figure

14b). It is assumed that

the gases have had to cross a greater amount of low-porosity rocks before

filling the reservoirs. It is also worth mentioning that a direction of

migration

migration may be deduced from this approach from the degree of fractionation of

the parameters involving methane and from the V2 values (Figures

12b, 14b). In

the platform fields of the Espirito Santo basin, the determined direction is

perfectly coherent with the knowledge of geology and oils geochemistry,

indicating an east-west gas

may be deduced from this approach from the degree of fractionation of

the parameters involving methane and from the V2 values (Figures

12b, 14b). In

the platform fields of the Espirito Santo basin, the determined direction is

perfectly coherent with the knowledge of geology and oils geochemistry,

indicating an east-west gas  migration

migration from the deepest parts of the margin to

the onshore platform, where the gases were sampled (Figure

14b). Estrella et al.

(1984) also suggested a long-distance

from the deepest parts of the margin to

the onshore platform, where the gases were sampled (Figure

14b). Estrella et al.

(1984) also suggested a long-distance  migration

migration , when the hydrocarbon pods lie

deeper eastward in the offshore part of the basin. Thus, lateral updip

long-distance

, when the hydrocarbon pods lie

deeper eastward in the offshore part of the basin. Thus, lateral updip

long-distance  migration

migration occurs through the excellent SÒo Mateus sandstone

carrier beds sealed by the Rio Itaunas evaporitic beds. The accumulations were

controlled by structural closure occurring at the same stratigraphic level (Figure

14b). This self-consistency between gas parameters and clear geological

observations reinforces the fact that the gas signatures may give

valuable information on the directions of

occurs through the excellent SÒo Mateus sandstone

carrier beds sealed by the Rio Itaunas evaporitic beds. The accumulations were

controlled by structural closure occurring at the same stratigraphic level (Figure

14b). This self-consistency between gas parameters and clear geological

observations reinforces the fact that the gas signatures may give

valuable information on the directions of  migration

migration and on the distance of

and on the distance of

migration

migration for a given sedimentological framework. The gas information as a

tracer thus becomes a powerful tool in basin modeling, providing from this

interpretation a consistent geometrical control for studies about maturity and

for a given sedimentological framework. The gas information as a

tracer thus becomes a powerful tool in basin modeling, providing from this

interpretation a consistent geometrical control for studies about maturity and

migration

migration paths.

paths.

The other example presented is the Recncavo basin in Brazil

(Figure 15), and is part of an intracontinental north-south aborted rift basin

immediately preceding the opening of the Atlantic ocean (Figueiredo et al.,

1994). Samples were collected solely from reservoirs in the vicinity of the Mata

Catu fault, a major northwest-southeast fault system, crosscutting the whole

basin (Figueiredo et al., 1994). Several hydrocarbon fields are located just

along the fault, whereas other fields are set on a perpendicular line centered

in the deepest part of the basin close to the hydrocarbon kitchens (Table

6).

The data are presented on Figures 16 and

17 for the Gastar diagrams and PCA,

respectively, with a distinction for the gases collected along the fault and the

gases collected in a transept perpendicular to the fault. Gases located at the

apex of the maximum of maturity of the source rocks and perpendicular to the

Mata Catu fault do not show any fractionation due to  migration

migration but do show a

clear maturity gradient. On the contrary, gases along the fault show an

important trend of segregative

but do show a

clear maturity gradient. On the contrary, gases along the fault show an

important trend of segregative  migration

migration with a consistent evolution with regard

to their position along the fault. Figure 18 presents the values of the V2 Eigen

vector vs. an approximate distance measured along the fault and expressed in

kilometers. The zero distance corresponds to the deepest section of the basin

along the fault. There is an excellent trend vs. the geometric positions of the

wells, indicating a long-distance

with a consistent evolution with regard

to their position along the fault. Figure 18 presents the values of the V2 Eigen

vector vs. an approximate distance measured along the fault and expressed in

kilometers. The zero distance corresponds to the deepest section of the basin

along the fault. There is an excellent trend vs. the geometric positions of the

wells, indicating a long-distance  migration

migration from the southeast portion of the

fault (where the kitchen is located) through the northeast area. This reinforces

the idea about the absence of any other kitchen in the northwestern area. We

have also determined that no correlation is observed between this V2 parameter

and the reservoir depth, demonstrating that bacterial contamination cannot be

responsible for the variation of the V2 parameter (mainly controlled by the

carbon isotopic signature of methane). If there were some bacterial

contamination, it would appear in shallower gas pools. This is the first time

that a fault may be seen as a segregative drain by looking at the geochemical

signatures of the gases. Major fault systems may play an important role for

hydrocarbon migrations and may be monitored using this type of geochemical

study.

from the southeast portion of the

fault (where the kitchen is located) through the northeast area. This reinforces

the idea about the absence of any other kitchen in the northwestern area. We

have also determined that no correlation is observed between this V2 parameter

and the reservoir depth, demonstrating that bacterial contamination cannot be

responsible for the variation of the V2 parameter (mainly controlled by the

carbon isotopic signature of methane). If there were some bacterial

contamination, it would appear in shallower gas pools. This is the first time

that a fault may be seen as a segregative drain by looking at the geochemical

signatures of the gases. Major fault systems may play an important role for

hydrocarbon migrations and may be monitored using this type of geochemical

study.

The use of all the available geochemical data associated

with some experimental controls on the processes affecting the chemical and

isotopic signatures of hydrocarbon gases improves the usefulness of these gases

in hydrocarbon exploration. Using diagrams based on experimental work and

statistical data analyses, we have shown for two Brazilian basins that it is

possible to reconstruct the hydrocarbon pathways, directions of migrations, and

degree of maturity of the source rocks associated with the gas. In the Espirito

Santo basin, the gas pools located in paleocanyons can be interpreted as

practically autochthonous, whereas the gases in the rift platform sediments

exhibit a longer  migration

migration from a kitchen located offshore. In the Reconcavo

basin, a major tectonic occurrence, the Mata Cata fault, plays a major role in

hydrocarbon

from a kitchen located offshore. In the Reconcavo

basin, a major tectonic occurrence, the Mata Cata fault, plays a major role in

hydrocarbon  migration

migration and accumulations in the southern part of the basin. This

gives a new and important control for petroleum systems evaluation.

and accumulations in the southern part of the basin. This

gives a new and important control for petroleum systems evaluation.

Arneth, J. D., and U. Matzigkeit, 1985, Variations in the carbon isotopic composition and production yield of various pyrolysis products under open and closed system conditions: Organic Geochemistry, v. 10, p. 1067-1071.

Barker, J. F., and S. J. Pollock, 1984, The geochemistry and origin of natural gases in southern Ontario: Bulletin of Canadian Petroleum Geology, v. 32, no. 3, p. 313-326.

Behar, F., S. Kressmann, J. L. Rudkiewicz, and M. Vandenbroucke, 1992, Experimental simulation in a confined system and kinetic modelling of kerogen and oil cracking: Organic Geochemistry, v. 19, no. 1-3, p. 173-189.

Berner, U., E. Faber, and W. Stahl, 1992, Mathematical simulation of the carbon isotopic fractionation between huminitic coals and related methane: Chemical Geology (Isotope Geoscience Section), v. 94, p. 315-319.

Berner, U., E. Faber., G. Scheeder, and D. Panten, 1995, Primary cracking of algal and landplant kerogens: kinetic models of isotope variations in methane, ethane and propane: Chemical Geology, v. 126, no. 3-4, p. 233-246.

Bondar, A. D., 1987, Role of diffusion in differentiation of carbon isotopes of methane of the Earth's crust (in Russian): Geokhimiya, v. 9, p. 1274-1283.

Chung, H. M., and W. M. Sackett, 1979, Use of stable carbon isotope compositions of pyrolytically derived methane as maturity indices for carbonaceous material: Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, v. 43, p. 1979-1988.

Chung, H. M., J. R. Gormly, and R. M. Squires, 1988, Origin of gaseous hydrocarbons in subsurface environment: theoretical considerations of carbon isotope distribution: Chemical Geology, v. 71, p. 97-103.

Clayton, C., 1991, Carbon isotope fractionation during natural gas generation from kerogen: Marine and Petroleum Geology, v. 8, p. 232-240.

Colombo, U., F. Gazzarrini, G. Sironi, R. Gonfiantini, and E. Tongiorgi, 1965, Carbon isotope composition of individual hydrocarbons from Italian natural gases: Nature, v. 205, p. 1303-1304.

Colombo, U., F. Gazzarrini, R. Gonfiantini, G. Sironi, and E. Tongiorgi, 1966, Measurement of C13/C12 isotope ratios on Italian natural gases and their geochemical interpretation, in P. A. Schenck and I. Havenaar, eds., Advances in organic geochemistry, 1964: Oxford, Pergamon, p. 279-292.

Colombo, U., F. Gazzarrini, R. Gonfiantini, G. Kneuper, M. Teichm³ller, and R. Teichm³ller, 1970, Carbon isotope study on methane from German coal deposits, in G. D. Hobson and G. C. Speers, eds., Advances in organic geochemistry, 1966: Oxford, Pergamon, p. 1-26.

Debart L., A. Morineau, and K. M. Warwick, 1984, Multivariate descriptive statistical analysis: correspondence analysis and related techniques for large matrices: New York, Wiley, 231 p.

Estrella, G., M. Rocha Mello, P. C. Gaglianone, R. L. M. Azevedo, K. Tsubone, E. Rossetti, J. Concha, and I. M. R. A. Bruning, 1984, The Espirito Santo basin (Brazil): source rock characterization and petroleum habitat, in G. Demaison and R. J. Murris, eds., Petroleum Geochemistry and Basin Evolution: AAPG Memoir 35, p. 253-271.

Faber, E., 1987, Zur Isotopengeochemie gasf÷rmiger Kohlenwasserstoffe: Erdol, Erdgas, Kohle, v. 103, no. 5, p. 210-218.

Faber, E., W. J. Stahl, and M. J Whiticar, 1992, Distinction of bacterial and thermogenic hydrocarbon gases, in R. Vially, ed., Bacterial gas: Paris, Editions Technip, p. 63-74.

Figueiredo, A. M. F., J. A. E. Braga, H. M. C. Zabalaga, J. J. Oliveira, G. A. Aguiar, O. B. Silva, L. F. Mato, L. M. F. Daniel, L. P. Magnavita, and C. H. L. Bruhn, 1994, Reconcavo basin, Brazil: a prolific intracontinental rift basin, in S. M. Landon, ed., Interior rift basins: AAPG Memoir 59, p. 157-203.

Franck, D. J., J. O. Smith, and W. M. Sackett, 1974, Reevaluation of carbon-isotope compositions of natural methanes: AAPG Bulletin, v. 58, p. 2319-2325.

Friedrich, H. U., and H. Juntgen, 1972, Some measurements of the 12C/13C ratio in methane or ethane desorbed from hard coal or released by pyrolysis, in H. R. Gaertner and H. Wehner, eds., Advances in organic geochemistry, 1971: Oxford, Pergamon, p. 639-646.

Fuex, A. N, 1980, Experimental evidence against an

appreciable isotopic fractionation of methane during  migration

migration , in A. G.

Douglas and J. R. Maxwell, eds., Advances in organic geochemistry, 1979: Oxford,

Pergamon, p. 725-732.

, in A. G.

Douglas and J. R. Maxwell, eds., Advances in organic geochemistry, 1979: Oxford,

Pergamon, p. 725-732.

Galimov, E. M., 1975, Carbon isotopes in oil-gas geology: NASA technical translation NASA TT F-682, 395 p.

Galimov, E. M., 1988, Sources and mechanisms of formation of gaseous hydrocarbons in sedimentary rocks, in M. Schoell, ed., Origins of methane in the Earth: Chemical Geology (special issue), v. 71, p. 77-95.

Hoering, T. C., and H. E. Moore, 1958, The isotopic composition of the nitrogen in natural gases and associated crude oils: Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, v. 13, p. 225-232.

James, A. T., 1983, Correlation of natural gas by use of carbon isotopic distribution between hydrocarbon components: AAPG Bulletin, v. 67, no. 7, p. 1176-1191.

James, A. T., 1990, Correlation of reservoired gases using the carbon isotopic compositions of wet gas components: AAPG Bulletin, v. 74, no. 9, p. 1441-1458.

Kaufman, R. L., A. S. Ahmed, and R. J. Elsinger, 1990, Gas chromatography as a development and production tool for fingerprinting oils from individual reservoirs: application in the Gulf of Mexico: Gulf Coast Section, SEPM Foundation Ninth Annual Research Conference Proceedings, p. 263-282.

Krooss, B. M., D. Leythauser, and R. G. G. Schaefer, 1992, The quantification of diffusive hydrocarbon losses through cap rocks of natural gas reservoirs--a reevaluation: AAPG Bulletin, v. 76, p. 403-406.

Krooss, B. M., S. Schlomer, R. Gaschnitz, and R. Littke,

1998, Aspects of natural gas generation and  migration

migration in sedimentary systems: V.

M. Goldschmidt conference 1998: Mineralogical Magazine, v. 62A, p. 818-819.

in sedimentary systems: V.

M. Goldschmidt conference 1998: Mineralogical Magazine, v. 62A, p. 818-819.

Lorant, F., A. Prinzhofer, F. Behar, and A. Y. Huc, 1998, Carbon isotopic and molecular constraints on the formation and the expulsion of thermogenic hydrocarbon gases: Chemical Geology, v. 147, p. 249-264.

Magnier, C., and A. Y. Huc, 1995, Pyrolysis of asphaltenes as a tool for reservoir geochemistry: Organic Geochemistry, v. 23, no. 10, p. 963-967.

Mattavelli, L., T. Ricchiuto, D. Grignani, and M. Schoell, 1983, Geochemistry and habitat of natural gases in Po basin, northern Italy: AAPG Bulletin, v. 67, p. 2239-2254.

Neglia, S., 1979,  Migration

Migration of fluids in sedimentary

basins: AAPG Bulletin, v. 63, p. 573-297.

of fluids in sedimentary

basins: AAPG Bulletin, v. 63, p. 573-297.

Nelson, J., and E. C. Simmons, 1992, The quantification of diffusive hydrocarbon losses through cap rocks of natural gas reservoirs--a reevaluation: discussion: AAPG Bulletin, v. 76, p. 1839-1841.

Nelson, J., and E. C. Simmons, 1995, Diffusion of methane and ethane through the reservoir cap rock: implication for the timing and duration of catagenesis: AAPG Bulletin, v. 79, p. 1064-1074.

Pernaton, E., A. Prinzhofer, and F. Schneider, 1996,

Reconsideration of methane signature as a criterion for the genesis of natural

gas: influence of  migration

migration on isotopic signature: Revue de l'Institut Francais

du Petrol, v. 51, no. 5, p. 635-651.