Extensional Fault-Bend Folding and Synrift

Deposition: An  Example

Example from the

from the  Central

Central Sumatra Basin, Indonesia*

Sumatra Basin, Indonesia*

John H. Shaw1, Stephen C. Hook1, and Edward P. Sitohang2

Search and Discovery Article #40004 (1999)

1Texaco Exploration and Production

Technology Dept., 3901 Briarpark, Houston, Texas 77042.

2PT CALTEX

Pacific Indonesia, Rumbai, Pekanbaru 28271, Indonesia.

* Published in AAPG Bulletin, V. 81, No. 3 (March 1997), P. 367-379; Figures 2,4, and 10 revised for online presentation.

Abstract

We describe an analytical method for interpreting

the geometry and structural history of asymmetric half grabens in

rift basins with extensional fault-bend fold theory. Using

seismic reflection profiles from the  Central

Central Sumatra basin and

balanced forward models, we show how local variations in tectonic

subsidence relative to deposition rates yield distinctive

patterns of folded synrift strata and unconformities that record

basin history. If the deposition rate exceeds the local

subsidence rate, folded growth strata form upwardly narrowing

kink bands that have been described previously as growth

triangles. In contrast, if the deposition rate is less than or

equals the local subsidence rate, growth strata are folded and

truncated at the surface on half-

Sumatra basin and

balanced forward models, we show how local variations in tectonic

subsidence relative to deposition rates yield distinctive

patterns of folded synrift strata and unconformities that record

basin history. If the deposition rate exceeds the local

subsidence rate, folded growth strata form upwardly narrowing

kink bands that have been described previously as growth

triangles. In contrast, if the deposition rate is less than or

equals the local subsidence rate, growth strata are folded and

truncated at the surface on half- graben

graben margins. Subsequent

increases in deposition rate relative to subsidence rate form

angular unconformities near the half-

margins. Subsequent

increases in deposition rate relative to subsidence rate form

angular unconformities near the half- graben

graben margins. These

unconformities develop without the necessity of erosion and are

folded by continuing fault slip. Strata above and below the

unconformities are concordant in the deeper parts of the half

grabens. Thus, angular unconformities on half-

margins. These

unconformities develop without the necessity of erosion and are

folded by continuing fault slip. Strata above and below the

unconformities are concordant in the deeper parts of the half

grabens. Thus, angular unconformities on half- graben

graben margins are

helpful for defining sequence boundaries that may reflect changes

in deposition and tectonic subsidence rates. In addition,

fault-bend fold interpretations yield fault geometry and measures

of horizontal extension, both of which control three-dimensional

half-

margins are

helpful for defining sequence boundaries that may reflect changes

in deposition and tectonic subsidence rates. In addition,

fault-bend fold interpretations yield fault geometry and measures

of horizontal extension, both of which control three-dimensional

half- graben

graben geometry and accommodation space. We show how

along-strike variations in fault geometry produce intrabasinal

structures that may form prospective fairways or local

depocenters.

geometry and accommodation space. We show how

along-strike variations in fault geometry produce intrabasinal

structures that may form prospective fairways or local

depocenters.

Introduction

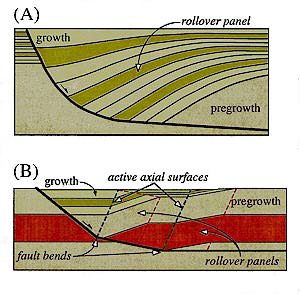

Half grabens form during crustal extension that is accommodated by normal faults, which commonly flatten with depth, causing collapse of the hanging wall and formation of inclined rollover panels (Hamblin, 1965). Many workers have presented geometric and physical models of hanging-wall collapse along vertical or steeply dipping shear surfaces (e.g., Gibbs, 1983; Jackson and Galloway, 1984; White et al., 1986; Rowan and Kligfield, 1989; Groshong, 1990; Nunns, 1991; White and Yielding, 1991; Withjack et al., 1995), including Coulomb shear along active fold hinges (Xiao and Suppe, 1992). The theory of Xiao and Suppe (1992) described how these active fold hinges, called active axial surfaces, are pinned at depth to fault bends and extend upward through prerift and synrift sections. As strata pass through these active axial surfaces due to fault slip, they are deformed into kink bands or inclined rollover panels. In areas of continuously curved or listric normal faults, where fault geometry can be strongly affected by sedimentary compaction, hanging-wall shear is generally distributed throughout the hanging-wall block (Figure 1A). Typically, syntectonic hanging-wall strata thicken gradually and fan toward the fault. In contrast, slip along normal faults composed of two or more planar segments produces hanging-wall shear along discrete axial surfaces related to fault bends (Figure 1B). Above faults composed of planar segments, rollovers are composed of planar segments, and growth strata thicken abruptly toward the fault above rollover panels.

Extensional Fault-Bend Folding

Purely rigid-block translation of the hanging wall over a normal fault that flattens with depth produces a large void between fault blocks that cannot be supported at depth. Collapse of hanging walls into these voids forms inclined fold limbs or "rollovers" above nonplanar faults (Hamblin, 1965); these rollovers have been observed in rift basins worldwide (e.g., Bally, 1983; James, 1984; Nunns, 1991). Xiao and Suppe (1992) modeled this hanging-wall collapse by Coulomb shear along inclined axial surfaces (Figure 2). During progressive fault slip, the hanging wall is sheared through active axial surfaces that are pinned to bends in the fault.

Figure 2 Extensional fault-bend fold models developed above a normal fault that flattens with depth (after Xiao and Suppe, 1992). (A) Incipient fault with a concave-upward bend; (B) antithetic hanging-wall rollover panel developed by shearing along the active axial surface in response to fault slip; (C) additional fault slip widens the rollover panel, which narrows upward into syntectonic (growth) strata forming a growth triangle. Growth strata deposited in the hanging-wall block are thickest above the more inclined fault segment. |

This hanging-wall shear along active axial surfaces is often accommodated in rocks and analog models by secondary faults that form above bends in the master normal fault and are translated away from these bends by slip on the underlying detachment (Dula, 1991; McClay and Scott, 1991; Xiao and Suppe, 1992; Withjack et al., 1995). Above concave-upward fault bends where the dip of the fault lessens with depth, rollover panels and active axial surfaces are generally oriented antithetic to the master fault (Figure 2) (Xiao and Suppe, 1992). Rollover panels are bounded by active axial surfaces and by parallel inactive axial surfaces, which mark the rocks that were initially along the active axial surface prior to fault slip. | |

| During progressive fault slip, inactive axial surfaces are translated away from active axial surfaces and, thus, intervening rollover panels widen as fault slip increases (Figure 2). | ||

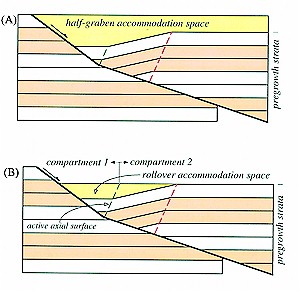

The geometries of normal faults and associated

rollover panels control the size and shape of accommodation

spaces in half grabens where sediments can be deposited.

Hanging-wall subsidence induced by fault slip produces an

accommodation space in the half  graben

graben , which is defined by the

maximum structural relief of the

, which is defined by the

maximum structural relief of the  top

top pregrowth horizon between

hanging-wall and footwall blocks (Figure 3A). In situations where

sediments evenly fill or overfill this accommodation space above

a single normal fault that flattens with depth, synrift strata

are thickest above the most inclined fault segments and thin in

the direction that the fault shallows (Figure 2). If normal

faults are composed of two or more planar segments, separate

compartments develop above each fault segment in the half grabens

(Figure 3B). Compartments are separated from each other by active

axial surfaces that are pinned to fault bends. Each half-

pregrowth horizon between

hanging-wall and footwall blocks (Figure 3A). In situations where

sediments evenly fill or overfill this accommodation space above

a single normal fault that flattens with depth, synrift strata

are thickest above the most inclined fault segments and thin in

the direction that the fault shallows (Figure 2). If normal

faults are composed of two or more planar segments, separate

compartments develop above each fault segment in the half grabens

(Figure 3B). Compartments are separated from each other by active

axial surfaces that are pinned to fault bends. Each half- graben

graben compartment has a distinct subsidence rate that is controlled by

the dip of the underlying fault segment.The rollover

accommodation space is defined by the structural relief across a

rollover panel, which represents the maximum structural relief

between adjacent half-

compartment has a distinct subsidence rate that is controlled by

the dip of the underlying fault segment.The rollover

accommodation space is defined by the structural relief across a

rollover panel, which represents the maximum structural relief

between adjacent half- graben

graben compartments (Figure 3B).

compartments (Figure 3B).

In contrast, where sediments underfill or exactly

fill the rollover accommodation space, other fold geometries

result (see Figure 4C, compartments 2 and 3). Under these

conditions, deposition is confined to the more rapidly subsiding

compartment 2, which is separated from the adjacent compartment 3

by an active axial surface (Figure 4). Growth strata deposited in

the more rapidly subsiding compartment 2, however, are translated

into the adjacent compartment 3 due to horizontal motion of the

hanging wall; this motion is induced by fault slip. As these

growth strata are sheared through the active axial surface, they

are folded into the rollover panel and crop out in angular

fashion at the surface. Although subsequent erosion may further

alter the geometry of growth strata at the surface, the angular

exposure is initially developed by folding and translation of

strata into areas of nondeposition. Subsequent deposition of

either postrift or synrift sediments above the truncated growth

strata generates an angular unconformity. Typically, angular

unconformities are interpreted to reflect distinct periods of

deformation, erosion, and then deposition; however, the growth

fault-bend fold models in Figure 4 demonstrate that angular

unconformities can develop in half grabens without erosion or a

hiatus in deformation due to increases in deposition rate

relative to subsidence rate, where half- graben

graben compartments

change from sediment-underfilled to overfilled conditions. In

Figure 4D, strata both above and below the angular unconformity

are syntectonic and become concordant in the deeper parts of the

half

compartments

change from sediment-underfilled to overfilled conditions. In

Figure 4D, strata both above and below the angular unconformity

are syntectonic and become concordant in the deeper parts of the

half  graben

graben .

.

Examples from the

Central

Central Sumatra Basin

Sumatra Basin

|

Figure 5 Map

showing the location of the  Central Central Sumatra basin on the

Island of Sumatra, Indonesia. Sumatra basin on the

Island of Sumatra, Indonesia. |

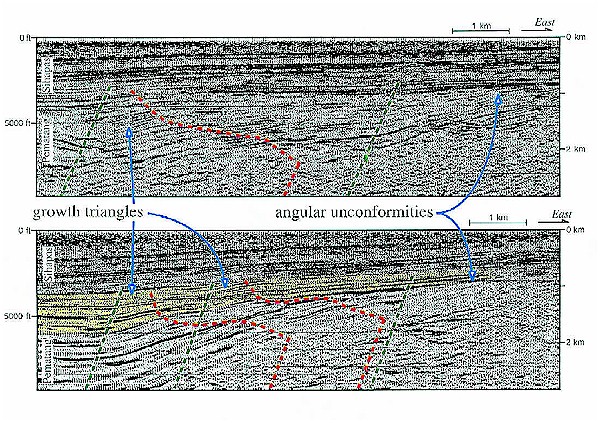

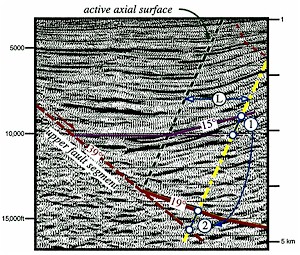

In the  Central

Central Sumatra basin (Figure 5), growth

triangles and unconformities, similar to those generated in our

fault-bend fold models, are observed in seismic images of

Tertiary lacustrine, fluvial, and marine strata (Figure 6). Using

a trough in

Sumatra basin (Figure 5), growth

triangles and unconformities, similar to those generated in our

fault-bend fold models, are observed in seismic images of

Tertiary lacustrine, fluvial, and marine strata (Figure 6). Using

a trough in  Central

Central Sumatra as an

Sumatra as an  example

example for our model, we

interpret the structural geometry and history of half grabens as

extensional fault-bend folds. Distinct axial surfaces separating

inclined from near-horizontal strata in this basin (Figure 6)

suggest that the underlying normal faults are composed of planar

segments. Furthermore, the migrated seismic reflection profiles

in Figure 6 image strata above and below the angular

unconformities that become concordant toward the center of the

troughs. Based on extensional fault-bend fold models (Figure 4),

these lateral changes from discordant to concordant strata

suggest significant increases in deposition rates relative to

subsidence rates through time. Collectively, these patterns of

folded strata enable us to decipher the structural and

depositional history of these half grabens using extensional

fault-bend fold theory (Xiao and Suppe, 1992).

for our model, we

interpret the structural geometry and history of half grabens as

extensional fault-bend folds. Distinct axial surfaces separating

inclined from near-horizontal strata in this basin (Figure 6)

suggest that the underlying normal faults are composed of planar

segments. Furthermore, the migrated seismic reflection profiles

in Figure 6 image strata above and below the angular

unconformities that become concordant toward the center of the

troughs. Based on extensional fault-bend fold models (Figure 4),

these lateral changes from discordant to concordant strata

suggest significant increases in deposition rates relative to

subsidence rates through time. Collectively, these patterns of

folded strata enable us to decipher the structural and

depositional history of these half grabens using extensional

fault-bend fold theory (Xiao and Suppe, 1992).

Figure 6 Examples of

growth triangles and angular unconformities in half grabens that

are imaged in migrated seismic reflection profiles from the

Central

Central Sumatra basin. Similar growth triangles and

unconformities are modeled in Figure 4 and are used to decipher

the underlying fault geometry and structural history of the

basin. Note how strata above the angular unconformities in the

east become concordant to the west in the deeper parts of the

half grabens. Datum (0 km) is sea level.

Sumatra basin. Similar growth triangles and

unconformities are modeled in Figure 4 and are used to decipher

the underlying fault geometry and structural history of the

basin. Note how strata above the angular unconformities in the

east become concordant to the west in the deeper parts of the

half grabens. Datum (0 km) is sea level.

The migrated seismic reflection profile in Figure 7 , which is displayed in depth,

images a half  graben

graben in the

in the  Central

Central Sumatra basin where Oligocene

strata thicken westward above an east-dipping normal fault that

is locally defined by a prominent fault-plane reflection. In the

uppermost part of the synrift section, at least three axial

surfaces separate horizontal strata on the left (west) from

inclined strata in rollover panels on the right (east) (Figure 7B). In the extensional fault-bend

fold models (Figure 4), the steeply dipping axial surfaces that

deform the synrift section are pinned at depth to bends in the

basin-forming normal fault. Therefore, we interpret these fold

hinges in Figure 7 as active axial

surfaces that are each pinned at depth to a discrete bend in the

underlying normal fault. Active axial surfaces are best located

by identifying changes in the dip of reflections in the uppermost

growth sequences (Figures 6, 7). These dip changes should be

consistent with the sense of simple shear induced by the fault

bend. For the concave-upward fault shapes described here, the bed

dip should be antithetic to the fault dip and should steepen in

the direction that the fault deepens. Alternatively,

convex-upward fault bends may yield panels that are synthetic to

the fault dip (Xiao and Suppe, 1992). In Figure

7, we extended the westernmost active axial surface downward

through fold hinges and used this orientation, which likely

reflects the Coulomb shear angle (Xiao and Suppe, 1992), to help

define the other, more poorly imaged axial surfaces. In other

cases, fold hinges may be more curved and less discrete if the

fault bends also are curved. Thus, a range of axial surface dips

(inclined shear orientations) should be tested (e.g., White et

al., 1986; Groshong, 1990). Moreover, subtle dip changes in

rollover panels are generally produced from subtle changes in

fault dip or other processes (e.g., differential compaction), and

the interpreter must decide upon the appropriate resolution of

structural dip changes.

Sumatra basin where Oligocene

strata thicken westward above an east-dipping normal fault that

is locally defined by a prominent fault-plane reflection. In the

uppermost part of the synrift section, at least three axial

surfaces separate horizontal strata on the left (west) from

inclined strata in rollover panels on the right (east) (Figure 7B). In the extensional fault-bend

fold models (Figure 4), the steeply dipping axial surfaces that

deform the synrift section are pinned at depth to bends in the

basin-forming normal fault. Therefore, we interpret these fold

hinges in Figure 7 as active axial

surfaces that are each pinned at depth to a discrete bend in the

underlying normal fault. Active axial surfaces are best located

by identifying changes in the dip of reflections in the uppermost

growth sequences (Figures 6, 7). These dip changes should be

consistent with the sense of simple shear induced by the fault

bend. For the concave-upward fault shapes described here, the bed

dip should be antithetic to the fault dip and should steepen in

the direction that the fault deepens. Alternatively,

convex-upward fault bends may yield panels that are synthetic to

the fault dip (Xiao and Suppe, 1992). In Figure

7, we extended the westernmost active axial surface downward

through fold hinges and used this orientation, which likely

reflects the Coulomb shear angle (Xiao and Suppe, 1992), to help

define the other, more poorly imaged axial surfaces. In other

cases, fold hinges may be more curved and less discrete if the

fault bends also are curved. Thus, a range of axial surface dips

(inclined shear orientations) should be tested (e.g., White et

al., 1986; Groshong, 1990). Moreover, subtle dip changes in

rollover panels are generally produced from subtle changes in

fault dip or other processes (e.g., differential compaction), and

the interpreter must decide upon the appropriate resolution of

structural dip changes.

| Only one segment of the fault is defined by a fault-plane reflection on the seismic profile in Figure 7; the adjacent fault segments are not imaged. The dips of the folded strata, the imaged fault segment, and the axial surfaces, however, can be used to predict the complete fault shape (Groshong, 1990; Dula, 1991; Xiao and Suppe, 1992). In extensional fault-bend folds, the magnitude of deflection of strata in a rollover panel is equal to the magnitude of fault deflection over the same width measured along the hanging-wall shear (axial surface) orientation (Figure 8). In Figure 8, reflections define an axial surface dip of 66°W and a bed dip of approximately 15°W in the westernmost rollover panel. Basing our prediction on the direction and magnitude of deflection of strata in the kink band, we believe that the fault steepens to a dip of about 39°E in the region west of the fault-plane reflection. Similar analyses for the remaining fault segments yield the entire fault trace on the seismic profile (Figure 7B). Along YY' in Figure 7, the fault consists of several segments that generally flatten with depth to a near-horizontal detachment. |  Figure 8 Fault

geometry derived from rollover shape. Enlarged portion of

the seismic line in Figure 7 annotated with a folded

horizon, an active axial surface, and the lower fault

segment (solid red line) based on fault-plane reflections

(see Figure 7A). The dip of the upper fault segment

(dashed red line) is derived from the rollover geometry.

The deflection of the folded horizon (1), measured at a

distance (L) along a line parallel to the |

By identifying active axial surfaces and

determining fault geometry, we have defined two basic geometric

elements of extensional fault-bend folds. Also significant,

however, are the positions of inactive axial surfaces, which

define the widths of rollover panels. In Figure

7, inactive axial surfaces in synrift section (growth axial

surfaces) are readily observed in the uppermost synrift section

because they bound dip domains of growth triangles. In contrast,

the positions of inactive axial surface in pregrowth or basement

sections are not as apparent. A fundamental relation between

kink-band width and fault slip, however, enables us to define the

positions of inactive axial surfaces. In extensional fault-bend

folds above a single normal fault that flattens with depth, the

true widths of all antithetic kink bands or rollover panels are

the same (Figure 9). This kink-band width is a measure of

horizontal extension and records the offset of any pregrowth

horizon measured between lines parallel to the hanging-wall shear

(axial surface) orientation that are pinned to correlative

hanging-wall and footwall cutoffs (Figure 9). In the  example

example from

the

from

the  Central

Central Sumatra basin (Figure 7), we

define the fault offset of the

Sumatra basin (Figure 7), we

define the fault offset of the  top

top pregrowth (basement) horizon

based on the fault shape and reflections tied from well control.

Based on the fault-bend fold models, this fault offset measured

between lines parallel to the hanging-wall shear orientation

equals the width of all antithetic kink bands developed in the

half

pregrowth (basement) horizon

based on the fault shape and reflections tied from well control.

Based on the fault-bend fold models, this fault offset measured

between lines parallel to the hanging-wall shear orientation

equals the width of all antithetic kink bands developed in the

half  graben

graben . Therefore, the offset of the

. Therefore, the offset of the  top

top basement horizon

across the normal fault in Figure 7 can

be used to define the positions of inactive axial surfaces in the

rest of the half

basement horizon

across the normal fault in Figure 7 can

be used to define the positions of inactive axial surfaces in the

rest of the half  graben

graben .

.

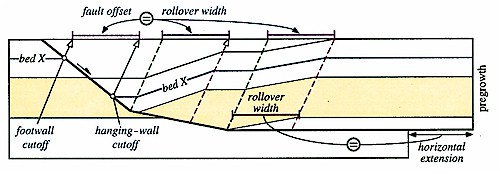

Figure 9 An extensional fault-bend fold model with two rollover panels developed above bends in a normal fault that flattens to a horizontal detachment. The widths of both rollover panels are the same and are equal to the horizontal extension on the detachment, although slip on each fault segment varies slightly based on fault dip. Rollover widths are also equal to the horizontal offset of any pregrowth horizon (e.g., bed X) across the fault measured between hanging-wall and footwall cutoffs projected along the hanging-wall shear (axial surface) orientation.

The recognition of axial surface shapes and

positions in growth and pregrowth sections, along with the

determination of fault geometry, describes the trough imaged in Figure 7 as a half  graben

graben developed by

extensional fault-bend folding. Proper application of fault-bend

folding theories yields area-balanced and retrodeformable

interpretations (Suppe, 1983; Xiao and Suppe, 1992).

Retrodeformable sections can be kinematically restored to a

reasonable, predeformation state without changes in rock area. To

demonstrate the internal consistency of the interpretation in Figure 7B, we generate a balanced-forward

model of the trough in Figure 10 using the fault geometry,

compacted stratigraphic thicknesses, and shear (axial surface)

orientation observed in the seismic profile. The retrodeformable

model conserves rock area, avoids gaps between fault surfaces by

shear along active axial surfaces, and forms rollover panels that

have widths related to fault slip. The final stage of the model

in Figure 10 depicts all the major structural elements of the

trough imaged in Figure 7, including the

shape of the

developed by

extensional fault-bend folding. Proper application of fault-bend

folding theories yields area-balanced and retrodeformable

interpretations (Suppe, 1983; Xiao and Suppe, 1992).

Retrodeformable sections can be kinematically restored to a

reasonable, predeformation state without changes in rock area. To

demonstrate the internal consistency of the interpretation in Figure 7B, we generate a balanced-forward

model of the trough in Figure 10 using the fault geometry,

compacted stratigraphic thicknesses, and shear (axial surface)

orientation observed in the seismic profile. The retrodeformable

model conserves rock area, avoids gaps between fault surfaces by

shear along active axial surfaces, and forms rollover panels that

have widths related to fault slip. The final stage of the model

in Figure 10 depicts all the major structural elements of the

trough imaged in Figure 7, including the

shape of the  graben

graben , the three growth triangles, and the angular

unconformity between Pematang and Sihapas strata. The consistency

between the geometries of the reflections and interpretation in Figure 7B and the final model in Figure 10

indicates that our interpretation of the trough as an extensional

fault-bend fold is internally consistent and viable.

, the three growth triangles, and the angular

unconformity between Pematang and Sihapas strata. The consistency

between the geometries of the reflections and interpretation in Figure 7B and the final model in Figure 10

indicates that our interpretation of the trough as an extensional

fault-bend fold is internally consistent and viable.

This increase generates an angular unconformity on the basin margin even though strata above and below the unconformity become concordant in the deeper part of the trough. In addition, the dips of the growth axial surfaces reflect this ratio of deposition rate relative to subsidence rate. In the Pematang section, which had a relatively low deposition rate relative to subsidence rate, the growth axial surface has a shallow dip (Figure 7). In contrast, the growth axial surface dips more steeply in the lowermost Sihapas section, which had a higher rate of deposition relative to subsidence rate.

The trough imaged in Figure 7

is one of several Tertiary half grabens in the  Central

Central Sumatra

basin that share a similar structural history (Eubank and Makki,

1981; Heidrick and Aulia, 1993). Our interpretation and modeling

of the trough imaged in Figure 7 as an

extensional fault-bend fold has important implications for the

structural and depositional histories of the basin. We conclude

that the master normal fault in the trough flattens with depth

and soles to near-horizontal detachment. The growth triangles

imaged on the seismic profiles are consistent with deposition of

the lacustrine and fluvial Pematang Group during formation of the

rift. Based on compacted thicknesses and fault slip recorded in

growth triangles, Pematang strata filled or slightly underfilled

the half-

Sumatra

basin that share a similar structural history (Eubank and Makki,

1981; Heidrick and Aulia, 1993). Our interpretation and modeling

of the trough imaged in Figure 7 as an

extensional fault-bend fold has important implications for the

structural and depositional histories of the basin. We conclude

that the master normal fault in the trough flattens with depth

and soles to near-horizontal detachment. The growth triangles

imaged on the seismic profiles are consistent with deposition of

the lacustrine and fluvial Pematang Group during formation of the

rift. Based on compacted thicknesses and fault slip recorded in

growth triangles, Pematang strata filled or slightly underfilled

the half- graben

graben accommodation space. Thus, the Pematang

deposition rate was generally equal to or slightly less than the

subsidence rate, producing shallowly dipping growth axial

surfaces (Figure 7). Most significantly,

the Brown Shale member of the Pematang formation, which has

sourced the more than 7 billion barrels of oil recovered from the

basin (Oil & Gas Journal, 1993), corresponds to a very

shallowly dipping segment of the growth axial surfaces (Figure 7B). This shallowly dipping growth

axial surface records a low rate of deposition relative to

subsidence rate that may reflect sediment-starved conditions in a

relatively deep lake, which is an environment suitable for the

deposition and preservation of organic materials. The upward

extension of these growth triangles in the lowermost marine

Sihapas Group also suggests that these sediments were locally

deposited during the latest stages of rifting. We demonstrate

that the angular unconformity on the eastern side of the basin

between Sihapas strata and the dipping Pematang section (Figures

5, 6) could have been generated by a dramatic increase in

deposition rate relative to subsidence rate without significant

uplift and erosion between deposition of fluvial-lacustrine and

marine units. This change in deposition rate relative to

subsidence rate may represent either a decrease in slip rate

during the waning stages of the rift or an increase in the

deposition rate of marine vs. older lacustrine and fluvial

sediments.

accommodation space. Thus, the Pematang

deposition rate was generally equal to or slightly less than the

subsidence rate, producing shallowly dipping growth axial

surfaces (Figure 7). Most significantly,

the Brown Shale member of the Pematang formation, which has

sourced the more than 7 billion barrels of oil recovered from the

basin (Oil & Gas Journal, 1993), corresponds to a very

shallowly dipping segment of the growth axial surfaces (Figure 7B). This shallowly dipping growth

axial surface records a low rate of deposition relative to

subsidence rate that may reflect sediment-starved conditions in a

relatively deep lake, which is an environment suitable for the

deposition and preservation of organic materials. The upward

extension of these growth triangles in the lowermost marine

Sihapas Group also suggests that these sediments were locally

deposited during the latest stages of rifting. We demonstrate

that the angular unconformity on the eastern side of the basin

between Sihapas strata and the dipping Pematang section (Figures

5, 6) could have been generated by a dramatic increase in

deposition rate relative to subsidence rate without significant

uplift and erosion between deposition of fluvial-lacustrine and

marine units. This change in deposition rate relative to

subsidence rate may represent either a decrease in slip rate

during the waning stages of the rift or an increase in the

deposition rate of marine vs. older lacustrine and fluvial

sediments.

Controls on Three-Dimensional Basin Geometry

Extensional fault-bend fold models demonstrate

that the sizes and shapes of the accommodation spaces in half

grabens are controlled by normal fault geometries, slip, and

axial surface orientations in the hanging-wall block (Xiao and

Suppe, 1992). These controls also affect three-dimensional basin

geometry; therefore, we apply the analytical techniques used to

interpret and model in two-dimensions to explore and map the

three-dimensional geometry of the half  graben

graben .

.

The hanging-wall shear orientation can be defined

by observing the dip of axial surfaces in seismic profiles. In

many cases, this dip corresponds to the Coulomb shear angle of

the rocks in extension and is roughly constant in basins composed

of the same rock types (Xiao and Suppe, 1992). Given a roughly

constant hanging-wall shear orientation, first-order highs and

lows within the basin are controlled by normal fault geometry and

slip. Thus, where fault geometry is constant along strike,

intrabasinal highs and lows are controlled by fault slip. Regions

of greater fault slip will have greater subsidence than areas of

less slip. Alternatively, where horizontal extension is constant,

lateral changes in fault inclination also form intrabasinal

structures. Folds above shallowly dipping fault segments will

remain high relative to folds along strike that overlie steeper

fault segments. We explore these effects of fault slip and

geometry in the  Central

Central Sumatra trough half

Sumatra trough half  graben

graben by using

fault-related fold theory to recognize and map horizontal

extension and to define fault geometry.

by using

fault-related fold theory to recognize and map horizontal

extension and to define fault geometry.

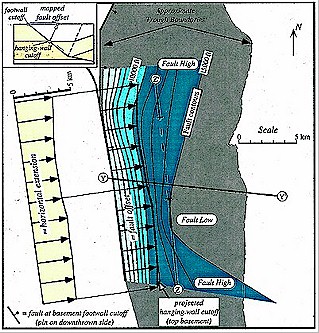

In extensional fault-bend folds that form by

simple shear, the offset of the hanging-wall and footwall cutoffs

of any pregrowth horizon is a measure of horizontal extension

above a normal fault that flattens with depth. This measure is

independent of fault dip magnitude (Figure 9). In Figure 11, we

map this horizontal extension across the trough imaged in Figure 7 using the hanging-wall and footwall

cutoffs on the  top

top of basement. In general, this horizontal

extension is roughly constant at about 3.3 km over the mapped

area. Thus, we speculate that variations in horizontal extension

along strike do not significantly affect the lateral geometry of

the trough and its accommodation space. Given this roughly

constant horizontal extension, we expect to see a direct

correlation between fault geometry and the shape of the

half-

of basement. In general, this horizontal

extension is roughly constant at about 3.3 km over the mapped

area. Thus, we speculate that variations in horizontal extension

along strike do not significantly affect the lateral geometry of

the trough and its accommodation space. Given this roughly

constant horizontal extension, we expect to see a direct

correlation between fault geometry and the shape of the

half- graben

graben accommodation space.

accommodation space.

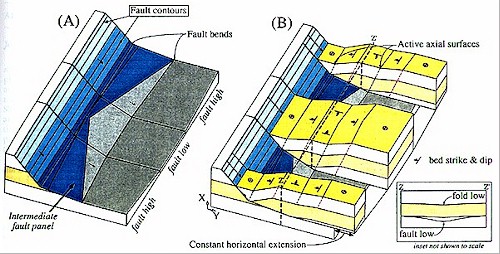

The fault map in Figure 11 was derived from the fault-plane reflections and rollover geometries in the trough imaged in Figure 7 and six other east-west-trending seismic reflection profiles. A simplified version of this fault geometry with three fault segments is shown in the three-dimensional model of Figure 12. The fault plane dips most steeply at shallow depths and flattens through two major (>10°) bends to a near-horizontal detachment. In the center of the trough along line YY', the intermediate fault panel is steep and the normal fault flattens to a horizontal detachment at about -5.3 km (-17,500 ft). Along strike on the northern and southern edges of the trough, the dips of the intermediate fault panel are less and the horizontal detachment lies at only about -4.6 km (-15,000 ft) (Figures 11, 12). As a result, the normal fault has a cuspate or bowl-like shape, with the steepest part of the intermediate fault segment lying just south of line YY'. A fault-bend fold model based on this fault shape with laterally constant horizontal extension (Figure 12) demonstrates that subsidence and accommodation space are greatest along the center of the trend.

Figure 12 Perspective

views of a three-dimensional fault-bend fold model of the trough

imaged in Figure 7. (A) Cuspate normal fault that flattens with

depth to a near-horizontal detachment, which is simplified from

the fault map in Figure 11. (B) Cutaway view of hanging-wall

rollover panels formed by plane strain with all transport vectors

in plane XY. Horizontal extension, which equals slip on the deep

near-horizontal fault segment, is constant along strike. The

central

central fault low corresponds to a

fault low corresponds to a  central

central basin fold low along

section ZZ' (inset).

basin fold low along

section ZZ' (inset).

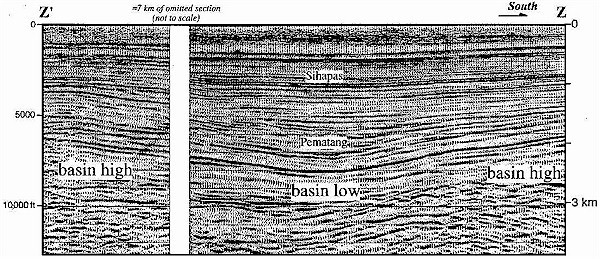

Therefore, we suggest that fault geometry, and not variable displacement, is responsible for defining the structurally lowest depocenter in the trough, which is imaged on strike lines through the basin (Figure 13). In addition to defining low spots, these measures of fault slip and geometry can define structural high points in the troughs that may serve to focus hydrocarbon accumulations. By identifying highs and lows along strike on normal faults, interpreters can quickly recognize depocenters and regional highs (Tearpock and Bischke, 1991), which can be tested by more detailed reflection contouring. Extensional fault-bend fold interpretations provide a method of defining fault planes using fold shape in cases without continuous fault-plane reflections or fault cuts in wells.

Figure 13 Migrated seismic reflection

profile ZZ' along the strike of the trough shown in Figure 11

that images a  central

central low area bounded to the north and south by

structural highs. Basin highs and lows are caused by lateral

changes in fault geometry, as shown in the model of Figure 12.

The omitted portion of the profile includes an area of younger

folding associated with faults other than the normal fault mapped

in Figure 11. Trace of seismic line ZZ' is shown in Figure 11.

Horizontal scale equals vertical scale; datum (0 km) is sea

level.

low area bounded to the north and south by

structural highs. Basin highs and lows are caused by lateral

changes in fault geometry, as shown in the model of Figure 12.

The omitted portion of the profile includes an area of younger

folding associated with faults other than the normal fault mapped

in Figure 11. Trace of seismic line ZZ' is shown in Figure 11.

Horizontal scale equals vertical scale; datum (0 km) is sea

level.

Summary and Conclusions

We demonstrated through our interpretation of seismic profiles

and forward models that extensional fault-bend folding has

controlled the structural evolution of a half  graben

graben in the

in the

Central

Central Sumatra basin. In addition, we recognized that

syntectonic deposits of fluvial-lacustrine and marine strata form

growth triangles and unconformities, which were produced by

variations between the rates of local deposition and subsidence.

We present a general method for using these patterns of folded

growth strata and fault-bend fold theory (Xiao and Suppe, 1992)

to define basin structure, including fault geometry. Fault and

fold maps based on our interpretations also demonstrated the

effects of variations in fault geometry on half-

Sumatra basin. In addition, we recognized that

syntectonic deposits of fluvial-lacustrine and marine strata form

growth triangles and unconformities, which were produced by

variations between the rates of local deposition and subsidence.

We present a general method for using these patterns of folded

growth strata and fault-bend fold theory (Xiao and Suppe, 1992)

to define basin structure, including fault geometry. Fault and

fold maps based on our interpretations also demonstrated the

effects of variations in fault geometry on half- graben

graben subsidence

and accommodation space. Fault highs and lows along strike in the

trough are overlain by fold highs and lows that form ridges and

depocenters. Collectively, fold and fault shapes provided the

basis for forward kinematic models of half-

subsidence

and accommodation space. Fault highs and lows along strike in the

trough are overlain by fold highs and lows that form ridges and

depocenters. Collectively, fold and fault shapes provided the

basis for forward kinematic models of half- graben

graben evolution that

were used to test the viability of our geologic interpretation.

General consistencies between fold and fault shapes generated in

forward models and imaged on seismic reflection data demonstrate

that extensional fault-bend folding (Xiao and Suppe, 1992) is a

viable theory for the origin of asymmetric half grabens in

basement-involved rift systems. Analytical techniques based on

this theory can be applied with limited seismic reflection data

to generate geometrically and kinematically reasonable

interpretations that define intrabasinal structures prior to

contour mapping of seismic reflections. In addition, fault-bend

fold models provide new interpretations of unconformities and

folded patterns of syntectonic section that help to decipher the

structural and depositional histories of rift basins.

evolution that

were used to test the viability of our geologic interpretation.

General consistencies between fold and fault shapes generated in

forward models and imaged on seismic reflection data demonstrate

that extensional fault-bend folding (Xiao and Suppe, 1992) is a

viable theory for the origin of asymmetric half grabens in

basement-involved rift systems. Analytical techniques based on

this theory can be applied with limited seismic reflection data

to generate geometrically and kinematically reasonable

interpretations that define intrabasinal structures prior to

contour mapping of seismic reflections. In addition, fault-bend

fold models provide new interpretations of unconformities and

folded patterns of syntectonic section that help to decipher the

structural and depositional histories of rift basins.

References Cited

Bally, A. W., ed., 1983, Seismic expression of structural styles: AAPG Studies in Geology 15, v. 2, variously paginated.

Dula, W. F., 1991, Geometric models of listric normal faults and rollover folds: AAPG Bulletin, v. 75, p. 1609-1625.

Eubank, R. T., and A. C. Makki, 1981, Structural geology of the Central

Central Sumatra back-arc basin: Proceedings of the

Indonesia Petroleum Association 10th Annual Convention,

p. 153-194.

Sumatra back-arc basin: Proceedings of the

Indonesia Petroleum Association 10th Annual Convention,

p. 153-194.

Gibbs, A. D., 1983, Balanced cross-section construction from seismic sections in areas of extensional tectonics: Journal of Structural Geology, v. 5, p. 153-160.

Groshong, R., 1990, Unique determination of normal fault shape from hanging-wall bed geometry in detached half grabens: Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae, v. 83, p. 455-471.

Hamblin, W. K., 1965, Origin of "reverse drag" on the downthrown side of normal faults: Geological Society of America Bulletin, v. 76, p. 1145-1164.

Heidrick, T. L., and K. Aulia, 1993, A structural and tectonic model of the Coastal Plains Block, Central

Central Sumatra basin, Indonesia: Proceedings of the Indonesia

Petroleum Association, 22 Annual Convention, p. 285-317.

Sumatra basin, Indonesia: Proceedings of the Indonesia

Petroleum Association, 22 Annual Convention, p. 285-317.

Jackson, M. P. A., and W. E. Galloway, 1984, Structural and depositional styles of Gulf Coast Tertiary continental margin: application to hydrocarbon exploration: AAPG Continuing Education Course Notes Series 25, 226 p.

James, D. M. D., ed., 1984, The geology and hydrocarbon resources of Negara Brunei Darussalam: Muzium Brunei, 164 p.

McClay, K. R., and A. D. Scott, 1991, Experimental models of hanging wall deformation in ramp-flat listric extensional fault systems: Tectonophysics, v. 188, p. 85-96.

Nunns, A. G., 1991, Structural restoration of seismic and geologic sections in extensional regimes: AAPG Bulletin, v. 75,

p. 278-297.

Oil & Gas Journal, 1993, Worldwide production report: Oil & Gas Journal, v. 91, p. 63-65.

Rowan, M. G., and R. Kligfield, 1989, Cross section restoration and balancing as an aid to seismic interpretation in extensional terranes: AAPG Bulletin, v. 73, p. 955-966.

Suppe, J., 1983, Geometry and kinematics of fault-bend folding: American Journal of Science, v. 283, p. 684-721.

Tearpock, D., and R. E. Bischke, 1991, Applied subsurface geological mapping: Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, Prentice-Hall, 648 p.

White, N. J., and G. Yielding, 1991, Calculating normal fault geometries at depth: theory and examples, in A. M. Roberts, G. Yielding, and B. Freeman, eds., The geometry of normal faults: Geological Society Special Publication 56, p. 251-260.

White, N. J., J. A. Jackson, and D. P. McKenzie, 1986, The relationship between the geometry of normal faults and that of the sedimentary layers in their hanging walls: Journal of Structural Geology, v. 8, p. 897-909.

Withjack, M. O., Q. T. Islam, and P. R. La Pointe, 1995, Normal faults and their hanging-wall deformation: an experimental study: AAPG Bulletin, v. 79, p. 1-18.

Xiao, H., and J. Suppe, 1992, Origin of rollover: AAPG Bulletin, v. 76, p. 509-525.- The authors thank Hongbin Xiao and John Suppe for helpful insights into their extensional fault-bend fold theory, which provided the foundation for this work. Exceptional reviews by M. Scott Wilkerson and Walter F. Dula, Jr., improved the manuscript. In addition, discussions with Karsani Aulia, Richard E. Bischke, Peter A. Brennan, Chris D. Connors, Paul W. Genovese, Tom L. Heidrick, and Elizabeth A. Lorenzetti provided insights into our structural interpretations and presentation of the theory. Seismic reflection data were provided by PT CALTEX Pacific Indonesia.