GCPrestack Impedance  Inversion

Inversion Aids Interpretation*

Aids Interpretation*

Satinder Chopra¹ and Ritesh Kumar Sharma¹

Search and Discovery Article #41664 (2015)

Posted August 17, 2015

*Adapted from the Geophysical Corner column, prepared by the authors, in AAPG Explorer, June, 2015, and entitled "Impedance  Inversion's

Inversion's Value in Interpretation".

Value in Interpretation".

Editor of Geophysical Corner is Satinder Chopra ([email protected]). Managing Editor of AAPG Explorer is Vern Stefanic. AAPG © 2015

¹Arcis  Seismic

Seismic Solutions, TGS, Calgary, Canada ([email protected])

Solutions, TGS, Calgary, Canada ([email protected])

In Impedance  Inversion

Inversion Transforms Aid Interpretation, Search and Discovery Article #41622 we described the different poststack impedance

Transforms Aid Interpretation, Search and Discovery Article #41622 we described the different poststack impedance  inversion

inversion methods that are available in our

methods that are available in our  seismic

seismic industry. In poststack

industry. In poststack  seismic

seismic

inversion

inversion – where there is no mode conversion at normal incidence – it is purely acoustic. P-wave impedance is the only information that can be estimated from poststack

– where there is no mode conversion at normal incidence – it is purely acoustic. P-wave impedance is the only information that can be estimated from poststack  inversion

inversion of P-wave

of P-wave  data

data . Prestack

. Prestack  inversion

inversion can be considered when the poststack

can be considered when the poststack  inversion

inversion is not effective enough to meet the desired objectives, such as differentiation of geologic strata or fluid information.

is not effective enough to meet the desired objectives, such as differentiation of geologic strata or fluid information.

In a  seismic

seismic gather, the near–offset amplitudes relate to changes in impedance of the subsurface rocks, and thus depict the correct time of the reflection events. The far-offset amplitudes relate to not only the changes in P-wave velocity and density, but the S-wave velocity as well. The

gather, the near–offset amplitudes relate to changes in impedance of the subsurface rocks, and thus depict the correct time of the reflection events. The far-offset amplitudes relate to not only the changes in P-wave velocity and density, but the S-wave velocity as well. The  inversion

inversion of far-offset amplitudes in a gather yields the elastic impedance (as was described in An 'Elastic Impedance' Approach, Search and Discovery Article #41082) and can be used for lithology and fluid discrimination. Thus prestack

of far-offset amplitudes in a gather yields the elastic impedance (as was described in An 'Elastic Impedance' Approach, Search and Discovery Article #41082) and can be used for lithology and fluid discrimination. Thus prestack  inversion

inversion has an advantage over poststack

has an advantage over poststack  inversion

inversion .

.

Another significant aspect of prestack impedance  inversion

inversion is that usually for thin layers in the subsurface, interference effects are reflected as amplitude distortions at different offsets and can be seen after NMO corrections of the

is that usually for thin layers in the subsurface, interference effects are reflected as amplitude distortions at different offsets and can be seen after NMO corrections of the  seismic

seismic gathers. Once the gathers are stacked, however, this information gets lost, and so poststack

gathers. Once the gathers are stacked, however, this information gets lost, and so poststack  inversion

inversion will not be able to retrieve it. Prestack

will not be able to retrieve it. Prestack  inversion

inversion considers the information in

considers the information in  seismic

seismic gathers and so is able to provide extra detail, which is not possible with poststack

gathers and so is able to provide extra detail, which is not possible with poststack  inversion

inversion . Prestack

. Prestack  seismic

seismic impedance

impedance  inversion

inversion also is commonly referred to as simultaneous

also is commonly referred to as simultaneous  inversion

inversion .

.

|

♦General statement ♦Figures ♦Method and Example ♦Conclusions

♦General statement ♦Figures ♦Method and Example ♦Conclusions

♦General statement ♦Figures ♦Method and Example ♦Conclusions

♦General statement ♦Figures ♦Method and Example ♦Conclusions

♦General statement ♦Figures ♦Method and Example ♦Conclusions

♦General statement ♦Figures ♦Method and Example ♦Conclusions |

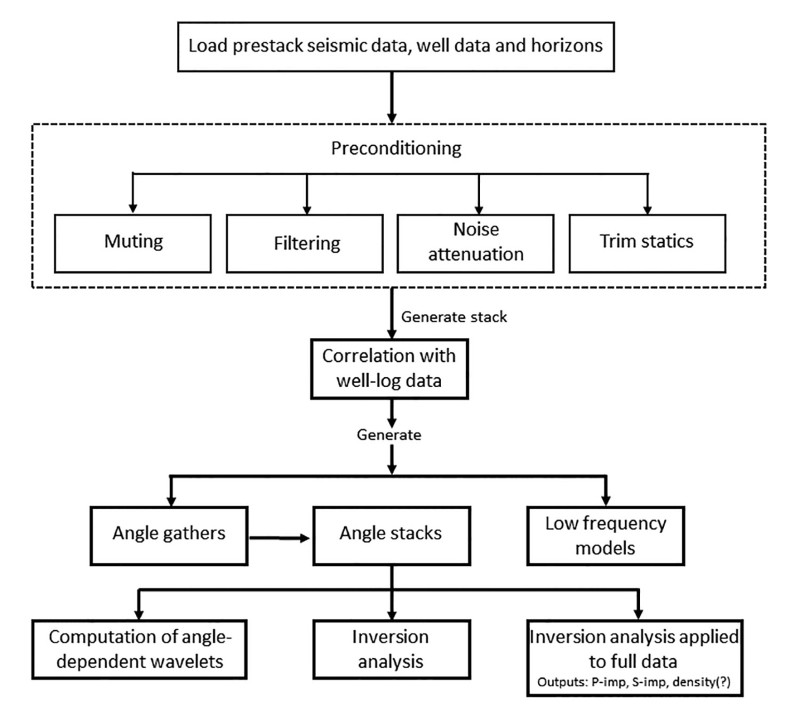

In simultaneous The workflow shown in Figure 1 explains the different steps followed in simultaneous The model impedance values are iteratively tweaked in such a manner that the mismatch between the modeled angle gather and the real angle gather is minimized in a least-squares sense. As a different wavelet is extracted for each partial angle stack and used in the Not only are the output components useable for interpretation of the physical rock properties, but the quality of the three elastic parameter outputs is enhanced in terms of better resolution. In Figure 3 we show segments of P-impedance sections from the 3-D

The stratigraphic column for this area was discussed in Impedance Shown on the display are the Doig, Halfway (indicated with light blue arrows) and the salt markers (yellow arrows), with shale and siltstone zone (green arrows) in between. Notice that the different zones are defined much better on the simultaneous Similarly, we show segments of S-impedance sections from the same 3-D Determining Formation Brittleness The discrimination of fluid content and lithology in a reservoir is an important characterization that has a bearing on reservoir development and its management. Lame's parameter Lambda (λ) is sensitive to pore fluid and is known as a proxy for incompressibility, whereas Mu (μ), the modulus of rigidity, is sensitive to the rock matrix. Referred to as the LMR approach, it consists of determining λρ and μρ from Once the P- and S- impedances are determined using simultaneous For unconventional reservoirs, such as shale resource formations, besides other favorable considerations that are expected of them, it is vital that reservoir zones are brittle. Brittle zones fracture better – and fracturing of shale resource reservoirs is required for their production. Among the different physical parameters that characterize the rocks, Young's modulus (E) is a measure of their brittleness. Attempts are usually made to determine this physical constant from well log For studying lateral variation of brittleness in an area, 3-D A new attribute (Eρ) in the form of a product of Young's modulus and density has been introduced, which was discussed in An Effective Way to Find Formation Britleness, Search and Discovery Article #41024. For a brittle rock, both Young's modulus and density are expected to be high, and so the Eρ attribute would exhibit a high value and serve as a brittleness indicator. The new attribute also can be used for litho-fluid detection, when it is used in conjunction with the product of bulk modulus and density. All this is possible with prestack simultaneous |