![]() Click to view article in PDF format.

Click to view article in PDF format.

Improved Techniques for Acquiring Pressure and Fluid Data in a Challenging Offshore Carbonate Environment*

K.D. Contreiras1, F. Van-Dúnem1, P. Weinheber2, A. Gisolf2, and M. Rueda2

Search and Discovery Article #40433 (2009)

Posted August 10, 2009

*Adapted from expanded abstract prepared for AAPG International Conference and Exhibition, Cape Town, South Africa, October 26-29, 2008.

1Schlumberger ([email protected] )

2Total

3ENI

The combination of low permeability, oil base mud and near

saturated oils presents one of the most challenging environments for fluid

sampling

sampling with formation testers. Low permeability indicates that the drawdown

while

with formation testers. Low permeability indicates that the drawdown

while  sampling

sampling will be high but this is contra-indicated for oils that are

close to saturation pressure. A logical response is to therefore reduce the

flow rate but in wells drilled with OBM an unacceptably long clean-up time

would result.

will be high but this is contra-indicated for oils that are

close to saturation pressure. A logical response is to therefore reduce the

flow rate but in wells drilled with OBM an unacceptably long clean-up time

would result.

The Pinda formation in Block 2 offshore Angola presents just such a challenge. Formation mobilities are in the low double or single-digits, saturation pressure is usually within a few hundred psi of formation pressure and borehole stability indicates that the wells must be drilled with oil base mud.

In the course of several penetrations of the Pinda formation a number of attempts were made to acquire representative formation samples but were stymied due to either excessive drawdowns that corrupted the fluid or by excessive contamination levels that rendered the samples unsuitable for laboratory analysis. Clearly a more flexible solution was required.

In this paper we review the results from previous attempts in the

Pinda. We show the pre-job modeling that was done to predict the required flow

rates and the anticipated drawdowns. Ultimately a two-step solution was used.

We first ran a high efficiency pretest-only WFT in order to quickly gather

formation pressure data and mobility data. This data was then used to design

the  sampling

sampling string which was a combination of an inflatable dual packer with

focused probe. We discuss the decision process that governed the choice of

pump, displacement unit, probe and packer. We pay particular attention to the

unique pump configurations that were required to effectively manage the

drawdowns when using the probe and also to allow sufficient flow rate when

using the dual packer.

string which was a combination of an inflatable dual packer with

focused probe. We discuss the decision process that governed the choice of

pump, displacement unit, probe and packer. We pay particular attention to the

unique pump configurations that were required to effectively manage the

drawdowns when using the probe and also to allow sufficient flow rate when

using the dual packer.

uExample 1 – Focused Probe uExample 2 – Dual Packer

uExample 1 – Focused Probe uExample 2 – Dual Packer

uExample 1 – Focused Probe uExample 2 – Dual Packer

uExample 1 – Focused Probe uExample 2 – Dual Packer

uExample 1 – Focused Probe uExample 2 – Dual Packer

uExample 1 – Focused Probe uExample 2 – Dual Packer

uExample 1 – Focused Probe uExample 2 – Dual Packer

uExample 1 – Focused Probe uExample 2 – Dual Packer

|

The Pinda was deposited in a shallow marine environment and is rich in carbonates and is frequently highly dolomitized. In such complex reservoirs the acquisition of quality formation tester samples is crucial to the reservoir evaluation. In this paper we wish to discuss results from previous attempts in the same area, the subsequent recommendations that were made and their implementation. This discussion is informed by the fact that these are low permeability rocks drilled with oil base mud, containing oils that are very close to saturation pressure.

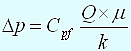

The interplay between formation characteristics and tool operation is described by the implementation of Darcy’s law (Moran and Finklea, 1962; Schlumberger, 2006) as seen in Equation 1.

As can be seen the drawdown at the sand face is a function of the mobility (k/μ), the flow rate and the probe size. Therefore in order to minimize the drawdown and stay above the bubble point it is required to either reduce the flow rate or increase the probe size. However neither of these options is without consequence. When the flow rate is reduced we will reduce the drawdown but the resulting very low flow rates imply it will take much longer to clean up the oil base mud filtrate. Similarly, a larger probe size permits a larger flow rate for a given drawdown but also allows for less sealing area for the packer as the flowing area is increased. The sealing success rate must be balanced against the requirements for drawdown and flow rate.

The question is then posed: how to design a

The inflatable dual packer uses two inflatable rubber elements to isolate and communicate with the reservoir. The spacing between the packer elements is adjustable however the nominal spacing is about 1.0 metre. Whereas the probes discussed earlier have a flow area that ranges anywhere from 0.15 to about 2 square inches, the dual packer, when inflated in an 8.5 inch borehole will isolate a flow area of about 960 square inches. This obviously leads to a huge reduction in drawdown for a given flowrate and mobility. We can model the performance of the probes and packers. The results of this modeling are presented in Table 2 and assume a formation mobility of 50 mD/cp.

As can be seen the inflatable dual packer presents considerable advantage in terms of reduced drawdown, increased flow rate or both. However, the advantages of the dual packer do not come without consideration. The dual packer is typically longer on station. Inflate and deflate times are longer than the set and retract sequences for a single probe. Additionally, when considering clean-up time, it is now necessary to clean up a cylinder that is 1.0 metre in height as opposed to the cone of fluid associated with a probe type of tool. This can take quite a bit longer. Finally, extended on-station times and larger tool diameter often dictate the inflatable dual packer is run drill pipe conveyed instead of on wireline which greatly increases the costs associated with rig time.

As the above discussion shows, in lower permeability reservoirs

where there is a drawdown constraint due to saturation pressure, we will

either be forced to use a dual packer with its attendant considerations or,

if we elect to use a probe, forced to pump at very low flow rates. The low

flow rates, however, present a problem for

Consider in Figure 1

a conventional

(non-focused) probe. We show in this figure a packer set against the borehole

wall (left hand side). We assume that the near wellbore fluid, in

yellow-green, is invaded filtrate and that the far field virgin fluid, in

blue, is the desired formation fluid. After the tool is set and the pretest

is complete the pump is started to begin the evacuation of fluid from the

formation and into the wellbore. In the case of a conventional

Now consider the schematic of the focused

Example

1 – Focused Probe

We look first at the focused

At point ‘B’ at about 2900 s the lower pumpout module is stopped

and the upper pumpout is started. The flow rate achieved is a very low 1.1

cc/s and the resultant drawdown is only 80 psi. Note that the inner bypass is

still open so guard and sample are still reading the same pressure. This 80

psi translates to a flowing mobility of about 21 mD/cp. At about 7400 s the

inner bypass is closed and both pumps are activated. This is the “split flow”

mode. Initially the guard side pump is started at 2.3 cc/s and the sample

side pump is started at 1 cc/s. Note immediately that the pressure on the

sample side starts to fall as drawdown increases. It is interpreted that this

is likely due to an increase in sample side viscosity as the lower viscosity

filtrate is directed to the guard side and the higher viscosity reservoir oil

heads towards the sample side. Eventually the pressure on the sample side

falls lower than on the guard side (sample side drawdown is higher). As

described earlier this is an undesirable situation. Best results are obtained

when the drawdown on the guard exceeds the drawdown on the sample so as to

encourage the separation of filtrate from reservoir oil. Therefore at about

9400 s the engineer begins stepped increases in the guard side pump speed in

order to increase the guard drawdown. By ~7500 s this is achieved and

Example

2 – Dual Packer

Multiple attempts to acquire a water sample in the lower part of the reservoir with a probe only resulted in high drawdown low mobility pretests. It was therefore decided to inflate the dual packer. Figure 4 shows the sequence. At point ‘A’ we see the lower pump being used to inflate the packer. During all of time period ‘A’ we are in pump-in mode to inflate the packers. At point ‘B’ we switch to pump-out mode and begin the drawdown from the formation. After initially running the lower pump at ~450 rpm the pump is slowed to 300 rpm and the flowing pressure stabilizes. The stable Δp is about 700 psi below formation pressure and the flow rate is about 1.8 cc/s. This corresponds to a mobility of about 0.2 mD/cp. At point ‘C’ the lower pump is turned off and the upper pump is started. Recall that the upper pump is configured with an extra High Pressure displacement unit (the same as the lower pump) but with a fixed displacement hydraulic pump set at about 0.3 cc/rev. As a result even a relatively high pump speed of 650 rpm results in only a 1.5 cc/s flow rate and slightly less Δp. The points marked with ‘X’ indicate where the sample bottles are filled. All of the samples obtained were less than 5% OBM filtrate (by volume).

Of course it is acknowledged that there is a lower limit to permeabilities that may be sampled with the probe type tools. To that end an inflatable dual packer is also included in the tool string and successfully deployed to acquire a water sample and confirm the location of the transition zone. For further information see Contreiras et al, 2008.

Akurt R., et al; 2006, Focusing on Downhole Fluid

Beaiji, T, M. Zeybek, R. Crowell, R. Akkurt, S. Al-Dossari, A. Amin,

and S. Crary; 2007, Advanced Formation Testing in OBM Using Focused Fluid

Dong, C., C. Del Campo, R. Vasques, P. Hegeman, and N. Matsumoto,

2005, Formation Testing Innovations for Fluid

Hammond, P.S., 1991, One- and Two-Phase Flow During Fluid

Contreiras, K.K., F. Van-Dúnem, P. Weinheber, A. Gisolf, and M. Rueda; 2008, Improved Techniques for Acquiring Pressure and Fluid Data in a Challenging Offshore Carbonate Environment: SPE 115504, SPE ATCE in Denver, CO., 21-24 September, 2008.

Moran, J.H., and E.E. Finklea, 1962, Theoretical Analysis of Pressure Phenomena Associated with the Wireline Formation Tester: SPE Journal of Petroleum Technology, August 1962; SPE 00177.

O'Keefe, M., K.O. Eriksen, S. Williams, D. Stensland, and R. Vasques;

2006, Focused

Schlumberger Educational Services Fundamentals of Formation Testing 2006.

Weinheber, P.J. and R. Vasques, 2006, New Formation Tester Probe

Design for Low-Contamination

Weinheber, P.J., A. Gisolf, R.J. Jackson, and I. De Santo, 2008,

Optimizing Hardware Options for Maximum Flexibility and Improved Success in

Wireline Formation Testing,

|