Click to view article in PDF format.

Click to view article in PDF format.

Geothermal Gradients and Subsurface Temperatures in the Northern Gulf of Mexico*

By

Joseph Forrest1, Ettore Marcucci1 and Paul Scott2

Search and Discovery Article #30048 (2007)

Posted February 25, 2007

*Adapted from article prepared for presentation at GCAGS Convention, New Orleans, September, 2005, which was canceled due to Hurricane Katrina. Article is published in GCAGS Transactions, 2005, v. 55, p. 233-248. Appreciation is expressed to GCAGS for permission to post this article.

1Resource GeoServices LLC, 10700 Richmond Ave., Houston, Texas 77042 ([email protected])

2Marathon Oil Company, 5555 San Felipe Road, Houston, Texas 77056

Abstract

Geothermal gradients have been calculated in 1131 fields and wells, and a map has been prepared showing the below-mudline depth to the 300oF subsurface isotherm over the northern Gulf of Mexico. Since the 300oF isotherm values are a direct reflection of thermal gradient, thermal conductivity, and heat flow, the map may be considered as a portrayal of subsurface temperature distribution. Based on interpreted vertical and horizontal temperature patterns, the northern Gulf can be subdivided into six thermal domains. The Texas shelf domain shows the highest subsurface temperatures with a pattern of elongate, northeast-trending isotherm contours related to the regional pattern of faulting. A prominent temperature high perpendicular to the regional trend may reflect the southeast-plunging San Marcos arch. The High Island domain coincides with a late Miocene depocenter and has anomalously low temperatures caused by either a deep overpressure zone or shallow thermal conductive zone. Moderately high temperatures and a pattern of isotherm contours related to salt features characterize the Louisiana shelf domain. The Mississippi Canyon domain coincides with the Mississippi fan and displays very low temperatures due to thermal suppression from thick, rapid Quaternary sedimentation. The Walker Ridge domain coincides with the Texas-Louisiana slope and has the coolest temperatures found to date in the northern Gulf. The Alaminos Canyon domain falls within the Northwest slope and the Perdido diapir provinces and displays temperatures intermediate in value between the Texas shelf and Walker Ridge domains.

|

|

Figure and Table Captions

Approximately 44,000 oil and gas

exploratory and development wells have been drilled in the US

Federal waters of the northern Gulf of Mexico since 1947 (Figure

1). These wells have encountered a variety of temperature

conditions that range from abnormally low to abnormally high,

indicating that the pattern of subsurface heat in the basin is

complex. Limited

The

result of our analysis is a map that illustrates below-mudline (BML)

depths to the 300-degree (BMLD300) subsurface isotherm throughout

the northern Gulf. This map can be considered as a portrayal of

subsurface temperature distribution, as the BMLD300 values are a

direct reflection of thermal gradient, thermal conductivity, and

heat flow. The map illustrates the complexity of subsurface

temperatures in the northern Gulf. In some cases this complexity can

be related to known

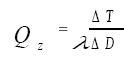

Geothermal Gradients in the Northern Gulf of MexicoIt is well established that temperatures increase with depth in the Earth, indicating that heat is generated at depth and transferred through rock and sediment layers to the surface. This so-called terrestrial heat flow is described by the following equation:

where:

Qz = Heat flow per unit area in the vertical direction l = Thermal conductivity

Blackwell and Richards (2004) present the

most recent interpretation of heat flow in the Gulf of Mexico as

part of their Geothermal Map of North America, but little

Since heat flow and thermal conductivity

Problem of Mean Annual Surface TemperatureIn calculating geothermal gradient using equation 2 a value of mean annual surface temperature is subtracted from the measured BHT before being divided by the formation depth. The mean annual surface temperature serves as an approximation of temperature at the top of the rock-sediment column. For the Texas Gulf Coast area an annual mean surface temperature of 68-70°F is typically applied. Because of the intervening water column, the air temperature in offshore areas does not truly reflect temperature at the top of the rock-sediment column (i.e., the mudline) and, therefore, may produce spurious results in geothermal gradient calculations. This is especially true in deep-water areas, where the mean air temperature at the water surface may be considerably higher than the temperature at the seafloor, or mudline. For the present study, we have used the mean annual temperature at the mudline as the “surface temperature,” thus eliminating the misleading influence of a water column that is not in thermal equilibrium with the underlying rock-sediment section. This standard has also been adopted recently by both API Subcommittee 10 for estimating subsurface temperatures for cementing and API Subcommittee 13 for estimating subsurface temperatures for calculating the true density and viscosity properties of drilling fluids at actual well-bore temperatures.

Good The gradient calculated for each field or well is based therefore on a mud-line temperature that reflects the water depth at which the field or well occurs. The resulting BML geothermal gradient is a better reflection of heat flow and thermal conductivity in the field or well, without the misleading influence of the water column with its reversed (temperature decreasing with depth) and unrelated thermal gradient.

Calculating Geothermal Gradients and BMLD300 Values

Two sources of

The main

Average weighted values obviously do not

reflect all possible variation in temperatures in a field. However,

as discussed in an earlier section, obtaining a regional grid of

good static bottom-hole temperatures from wells is essentially

impossible in the Gulf. We recognize the weakness in the

Since the

To calculate gradients, an Excel

spreadsheet was developed that contained all After establishing the gradient lines, values were extracted from each plot to calculate a gradient and a BMLD300 value (Figures 5, 6, and 7). If a field demonstrated dogleg gradients (see next section for discussion), the temperature of the deepest point above the deepest dogleg was recorded, and the gradient of this last step was used to calculate the depth to reach 300°F in the field or well.

Dogleg Thermal GradientsA commonly observed phenomenon in the Gulf Coast and Gulf of Mexico is that geothermal gradients have two or more distinct linear segments, indicating that the gradient varies in a step-like fashion with depth. These gradient variations are often coincident, or near-coincident, with the top of overpressure in the stratigraphic section (Jones, 1969, Leftwich, 1993) or with a change in average thermal conductivity of the section (Blackwell and Steele, 1989). Hunt (1996) has referred to these zones of variable gradient as “dogleg geothermal gradients.”

In this study multi-linear, or dogleg,

geothermal gradients have been observed throughout the northern

Gulf, but not in all fields and wells. In many fields the gradient

trend shows no obvious change in rate (Figure

5). This may reflect the true gradient situation in the field,

or the Multiple doglegs are interpreted to occur in many fields in the study (Figures 6 and 7). Though it was out of the scope of the present work, we feel that mapping the distribution of dogleg thermal gradient zones could be useful in determining regional patterns of overpressure and thermal conductivity change.

Subsurface Temperature Distribution in the Northern Gulf

Mapping BMLD300 Values

To map the BMLD300 values we used the

field outlines published by the MMS in the 2001 Atlas study. A

latitude-longitude centroid was calculated for each field and this

was the point used to map the BMLD300 value in the field. Values for

wells were plotted at the bottom-hole locations. The completed Surfer map was converted to an ESRI (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Inc., 380 New York Street, Redlands, CA 92373) shapefile and loaded into ArcGIS 9.0 (trademark of ESRI). The contours were converted to closed polygons, and extraneous lines were cleaned up for final map presentation.

Distribution of Subsurface Temperatures in the GulfFigure 8 is the completed interpretation of BMLD300 values for the northern Gulf. The most remarkable aspect of temperature distribution is the distinct differentiation between shelf and deep-water areas. The shallowest BMLD300 values, and thus the highest thermal gradients and heat flow, occur on the Texas-Louisiana shelf, which is the area above 300 m (984 feet or approximately 1000 feet) water depth. At these water depths BMLD300 values range from 9700 feet to 45,000 feet, but these extremes are uncommon and restricted in occurrence; by far the most common depth range is 15,000– 19,000 feet. In the deep-water areas, below 300 m of water, the BMLD300 values range from 11,000 to 45,000+ feet, with most common range being from 21,000 to 37,000 feet. Further differentiations can be made within the deep-water areas between water depth-ranges of 300m-1000m and 1000m-2000m, but these distinctions are very subjective. In the shallower of these two ranges the BMLD300 values range from 11,000 to 45,000 feet, with the most common depths being 21,000 to 31,000 feet. Between 1000m and 2000m the BMLD300 values are 13,000 to 45,000+, with the most common values being from 21,000 to 37,000 feet. The average geothermal gradient, and therefore subsurface temperature, tends to be lower in the deep-water areas than on the shelf. This point is illustrated in Figure 9, which shows the range of BMLD300 values and the midpoint depth of the most prevalent range of BMLD300 for each protraction area in the northern Gulf (see Table 1 for summary). Though we feel that the general trend of cooler temperatures in deep-water areas is real, it should be noted that temperature patterns throughout the northern Gulf show a great range of variability. There are areas on the shelf that are nearly as cool as those in the deep- water, and areas in deep-water as warm as those on the shelf.

Temperature Domains

Even a casual glance at

Figure 8 suggests that the area of the

study can be divided readily into distinct areas of temperature

distribution. We have interpreted six “temperature domains,” which

we define as regional geographic areas that share noticeable

similarities in their temperature distribution patterns, which can

be related to

The Texas Shelf Domain

This area, which includes the Texas shelf

and a portion of the western shelf of Louisiana, has the highest

temperature gradients and broadest pattern of shallow BMLD300 values

in the northern Gulf of Mexico. The shallowest BMLD300 value occurs

in the Brazos 437 (BA437) field at 9700 feet. The range of BMLD300

values in the domain is 9700 to 25,000 feet, but the dominant depths

range from 13,000 to 17,000 feet. Several temperature patterns that

can be directly related to

High Island DomainWithin the Texas shelf domain is another anomalous area centered approximately in the High Island region. This area is bounded to the northwest by the Corsair fault trend and is the site of a late Miocene depocenter, as outlined by Winker (1982). BMLD300 values in the domain range from 17,000 to 23,000 feet, classifying it as anomalously cool in relationship to the surrounding Texas shelf domain. We speculate that a deep overpressure zone or a shallow conductive zone may underlie the High Island domain. Reference to Figure 1 shows that the High Island domain is also an area of remarkably low-drilling density.

Louisiana Shelf DomainThis area is characterized by BMLD300 values that range from 13,000 to 33,000 feet, with a most common range of 15,000 to 19,000 feet. In addition to being generally cooler than the Texas shelf domain the pattern of temperature distribution is dominated by numerous small “bulls-eye” contour anomalies, which contrast with the elongate pattern of contours on the Texas shelf. This pattern is most likely a reflection of salt dome tectonics that have produced the short, arcuate fault system pattern that characterizes the Louisiana shelf. High temperature anomalies are often associated with salt domes (Gretener, 1981). We have compared the pattern of BMLD300 anomalies to the pattern of known salt domes on the Louisiana shelf and find good general agreement, though not absolute coincidence. In an investigation of geothermal patterns around salt domes in south Louisiana, Kumar (1989) found that there is a general rise in temperatures in the vicinity of domes but that isotherms do not always conform to them.

Mississippi Canyon DomainThis deep-water area coincides with the Mississippi fan, a large complex that extends south from the edge of the Louisiana shelf to abyssal depths and consists of a thick section of Quaternary submarine deposits. BMLD300 values in the domain range from 23,000 to 43,000 feet, with the most common depths ranging from 27,000 to 37,000 feet. Mello and Karner (1996), Jones and Nagihara (2003), and Jones et al. (2003) have suggested that the rapid deposition of a thick section of young sediments in the fan has suppressed regional isotherms, resulting in anomalously low surface heat flow.

Walker Ridge domain

This deep-water domain coincides with the

Texas-Louisiana slope and is characterized by salt diapirism,

lateral emplacement of salt tongues and sheets, and from mass

downslope transport of surface sediments. Worrall and Snelson (1989)

have interpreted the Texas-Louisiana slope as a large overthrust

complex in which salt forms the basal thrust surface and in which

salt is tectonically thickened relative to the shelf areas. BMLD300

values range from 25,000 to 56,000 feet, with the most common values

in the range of 29,000 to 43,000 feet. It is tempting to relate the

deep BMLD300 values in some way to the dominance of salt-related

phenomena in the domain, but Jones et al. (2003) have concluded that

lateral salt tongues, such as those that characterize the

Texas-Louisiana Slope, do not affect heat flow. There is no evidence

in the domain of the rapid thick sedimentation that has formed the

Mississippi fan to the east. The low geothermal gradients in the

area are indeed anomalous, and we cannot relate them at the present

time to any known

The Alaminos Canyon Domain

This deep-water area displays BMLD300

values that are intermediate between those of the Texas Shelf and

Walker Ridge domains. The values range from 13,000 to 27,000 feet,

with predominant values from 21,000 to 25,000 feet. The area of the

Alaminos Canyon domain falls within two

Conclusions

Equilibrium bottom-hole temperature

Despite its

AcknowledgementsThe authors gratefully acknowledge the Synthetic-Based Mud Research Group for financial support of this project and for their permission, with that of the American Petroleum Institute, to publish this paper.

ReferencesBlackwell, D.D., and M. Richards, 2004, Geothermal Map of North America: AAPG. Blackwell, D.D. and J.L. Steele, 1989, Thermal conductivity of sedimentary rocks: measurement and significance, in Naeser, N.D., and T.H. McCulloh, eds., Thermal History of Sedimentary Basins: New York, Springer- Verlag. Bodner, D. P., and J.M. Sharp, 1988, Temperature variations in south Texas subsurface: American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, v. 72, no. 1, p. 21-32.

Ewing, T. and R. Flores,

1991, Principal structural features of the Gulf of Mexico basin,

in Salvador, A., ed., The Gulf of Mexico Basin: The Geology of

North America, v. J:

Ewing, T. E., 1991,

Structural framework, in Salvador, A., ed., The Gulf of

Mexico Basin: The Geology of North America, v. J: Gretener, P., 1981, Geothermics: Using temperature in hydrocarbon exploration: AAPG Education Course Note Series #17. Hunt, J. M., 1996, Petroleum Geochemistry and Geology, 2nd Ed.:, Freeman, San Francisco. Jones, K.O., and S. Nagihara, 2003, Sedimentary thermal maturation models for the deepwater eastern Gulf of Mexico: Transactions, GCAGS, v. 53, p. 374-383. Jones, M.L., S. Nagihara, and M.A. Smith, 2003, The regional geothermal heat flow regime of the north-central Gulf of Mexico continental slope: Transactions, GCAGS, v. 53, p. 363-373. Jones, P. H., 1969, Hydrodynamics of geopressure in the northern Gulf of Mexico basin: Journal of Petroleum Technology, v. 21, p. 803-810. Kumar, M. B., 1989, Geothermal patterns of Louisiana salt domes: Transactions, GCAGS, v. 39, p. 159-170. Leftwich, J. T., 1993, The development of zones of “undercompacted” shale relative to abnormal subsurface pressures in sedimentary basins: Unpublished PhD dissertation, Pennsylvania State University, Department of Geosciences. Lewis, C. R., and S.C. Rose, 1970, A theory relating high temperatures and overpressures: Journal of Petroleum Technology, v. 22, p. 11-16. Mello, U.T., and G.D. Karner, 1996, Development of sediment overpressure and its effect on thermal maturation: application to the Gulf of Mexico basin: AAPG Bulletin, v. 80, p. 1367-1396. Minerals Management Service, 2001, Atlas of Northern Gulf of Mexico Gas and Oil Sands: Minerals Management Service, U. S. Dept. of the Interior, New Orleans. Winker, C.D., 1982, Cenozoic shelf margins, northwestern Gulf of Mexico: Transactions, GCAGS, v. 32, p. 427-448.

Worrall,

D.M., and S. Snelson, 1989, Evolution of the northern Gulf of

Mexico, with emphasis on Cenozoic growth faulting and the role of

salt, in Bally, A.W., and A.R. Palmer, eds., The Geology of

North America – An Overview: |

(1)

(1)

........

(2)

........

(2)