![]() Click

to article in PDF format.

Click

to article in PDF format.

PSSeal Mechanisms In Shallow Sediments: Implications For Shallow-Water Flow And Gas-Hydrate Hazards*

By

T.J. Katsube1, K. O. Horkowitz2, I.R. Jonasson1, D. Piper3 and D. Issler4

Search and Discovery Article #40160 (2005)

Posted August 8, 2005

*Adapted from poster presentation at AAPG Annual Meeting, Calgary, Alberta, June 19-22, 2005.

1Geological Survey of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1A 0E8; Phone: 613-995-9239; Fax: 613-943-1286; email: [email protected]

2Resource Analysts, Sugar Land, TX USA;

3Geological Survey of Canada (Atlantic), Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada B2Y 4A2;

4Geological Survey of Canada (Calgary), Calgary, Alberta, Canada T2L 2A7.

Abstract

Experimental studies have shown that clay-rich sea

floor sediments can have permeabilities (k) as low as 100-1000 nD (10-19-10-18m2)

under confining pressures equivalent to sub-bottom depths of 200-500 m [1]. This

implies that poor quality  seals

seals could exist at relatively shallow depths

below the mud-line. Such

could exist at relatively shallow depths

below the mud-line. Such  seals

seals would likely be of poor integrity, but sufficient

as a cause for shallow water flow (SWF) with overpressures of 1-4 MPa

[2,3] above hydrostatic pressure. In addition, the following shallow seal

mechanisms can exist:

would likely be of poor integrity, but sufficient

as a cause for shallow water flow (SWF) with overpressures of 1-4 MPa

[2,3] above hydrostatic pressure. In addition, the following shallow seal

mechanisms can exist:

In areas of up-flowing gas, poor quality  seals

seals could

be sufficient to move the temperature-pressure regime of pore pressures into the

gas-hydrate stability zone and form gas-hydrate enhanced

could

be sufficient to move the temperature-pressure regime of pore pressures into the

gas-hydrate stability zone and form gas-hydrate enhanced  seals

seals in the

shallow sediments [4,5].

in the

shallow sediments [4,5].

There are indications that bacterial activity

can produce carbonate and sulphide cement by oxidation of methane gas and

reduction of sea water, respectively, and that these could form effective  seals

seals in areas of up-flowing gas [4,5].

in areas of up-flowing gas [4,5].

Shallow  seals

seals may also be formed by bound-water layer

thickness increase due to decreased temperatures [6].

may also be formed by bound-water layer

thickness increase due to decreased temperatures [6].

Shallow  seals

seals could also be formed by fluid expulsion

from shallow overpressured formations in areas of high sedimentation

rates [6].

could also be formed by fluid expulsion

from shallow overpressured formations in areas of high sedimentation

rates [6].

Uplifted conventional  seals

seals consisting of well compacted clay-rich shale

formations that have experienced maximum burial depths of more than 2.0-2.5 km

[1] with k values of less than 10-100 nD (10-20-10-19m2)

could exist below the mud-line.

consisting of well compacted clay-rich shale

formations that have experienced maximum burial depths of more than 2.0-2.5 km

[1] with k values of less than 10-100 nD (10-20-10-19m2)

could exist below the mud-line.

Shallow Seal Mechanisms

Clay Rich Seal

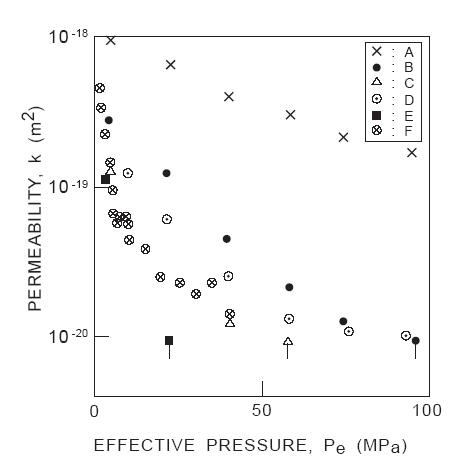

Figure B1: (Katsube et al., 1996)

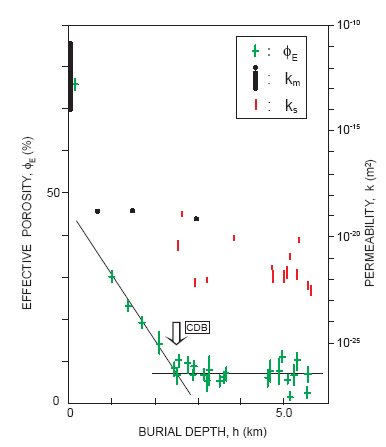

Recent experimental studies show (Figure B1)

that permeability (k) values of unconsolidated clay-rich sediments can be

reduced to less than 100 nD at effective pressures of less than 5 MPa [1]. This

implies that moderately good  seals

seals could be formed under relatively small

overburden pressures, if the clay content of the sediments are sufficiently

high, and that moderately good

could be formed under relatively small

overburden pressures, if the clay content of the sediments are sufficiently

high, and that moderately good  seals

seals can exist in the sediments at relatively

shallow depths (<500 m).

can exist in the sediments at relatively

shallow depths (<500 m).

Bacterial Seal

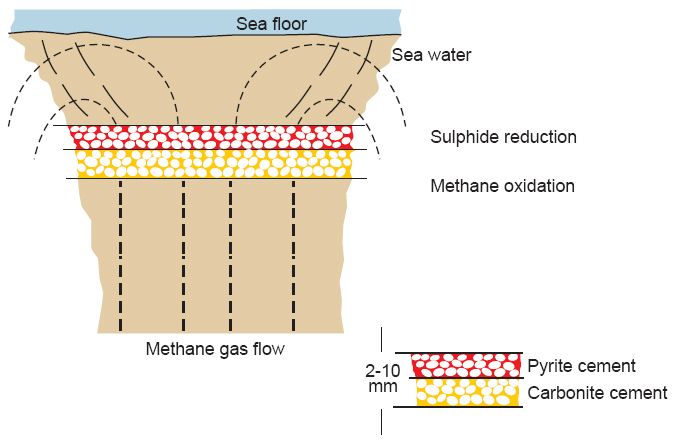

Figure B2: (Katsube and Jonnasson, 2002)

Bacterial activity can produce sulphide cement from reduction of sea water and carbonate cement from oxidation of up-flowing methane gas through shallow sediments (Figure B2) [9]. Thin layers (1-3 mm) of sulphide cement and carbonate cement were observed in sediments above a major gas-hydrate formations at depth of 900-1000 m which could have formed originally at shallower depth [10] as a result of bacterial activity [4]. The section containing these layers displayed very low permeability values (<100 nD).

Gas-Hydrate Seal

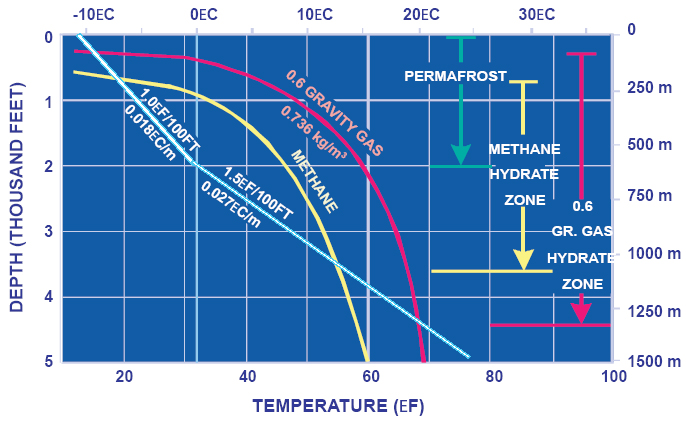

Figure B3: (Bily and Dick, 1974)

Gas-hydrates are stable only within a certain low temperature and elevated pressure regime (Figure B3) [13]. However, a sudden change in pressure or temperature at the sea floor could retard the free flow of up-flowing gas and move its temperature or pressure regime into the gas-hydrate stability zone [4]. The pressure changes could result from sudden sedimentation rate or clay content increases that could create a poor shallow seal, due to decreased permeability. These could cause gas-hydrates to form and act as a seal and further increase the gas pressure. This would move the temperature- pressure regime further into the gas-hydrate stability zone resulting in gas-hydrates to grow and form an enhanced thick and stable seal.

Uplifted Shale

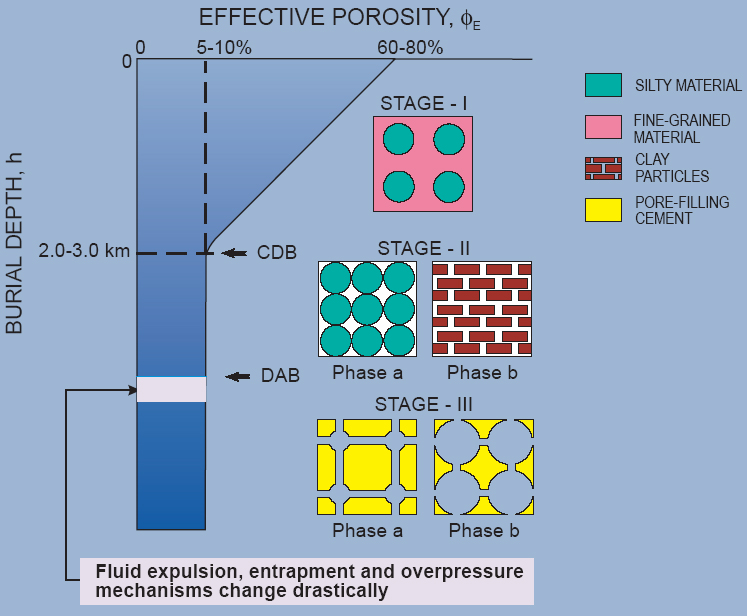

Figure B4a: (Katsube and Williamson, 1998; Katsube et al., 1998)

Figure B4b: Porosity (fE) and permeability (k) depth (h) curves for shale, mud and compacted mud samples (Katsube and Williamson, 1998), suggesting that k decreases with h at a greater rate than fE. The intersection between the two fE-h lines is the critical depth of burial (CDB).

Conventional  seals

seals consist of well compacted

clay-rich mudstone formations that have experienced maximum burial depths of

more than 2.0-2.5 km [1] and have hydraulic permeabilities (k) of less than

10-100 nano-Darcies, or 10-20-10-19m2

(Figures B4a & B4b). There are cases where good conventional

consist of well compacted

clay-rich mudstone formations that have experienced maximum burial depths of

more than 2.0-2.5 km [1] and have hydraulic permeabilities (k) of less than

10-100 nano-Darcies, or 10-20-10-19m2

(Figures B4a & B4b). There are cases where good conventional  seals

seals can

exist at shallow depth below the mudline, due to an uplifted formation.

can

exist at shallow depth below the mudline, due to an uplifted formation.

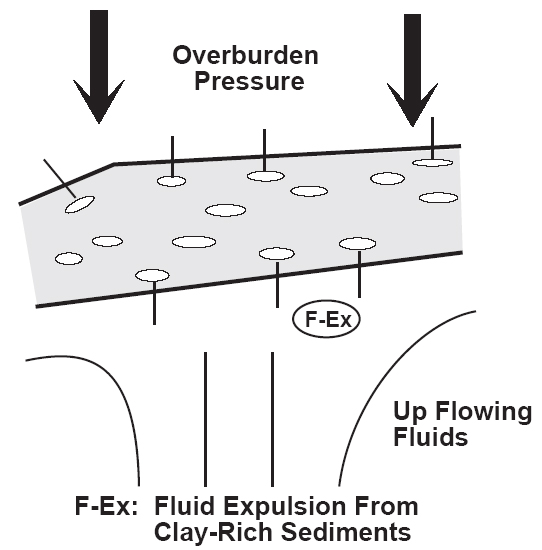

Overpressure Seal

Figure B5:

Rapid sedimentation is known to result in overpressured formations [14]. In such cases, fluids from the overpressured formation could be bleeding out into both the upper and lower formations (Figure B5) for prolonged periods of time [7]. While the overpressured fluids are being expelled and bleeding into the lower formations, they could retard the upward flowing fluids and act as a seal (Figure B5) for a limited time.

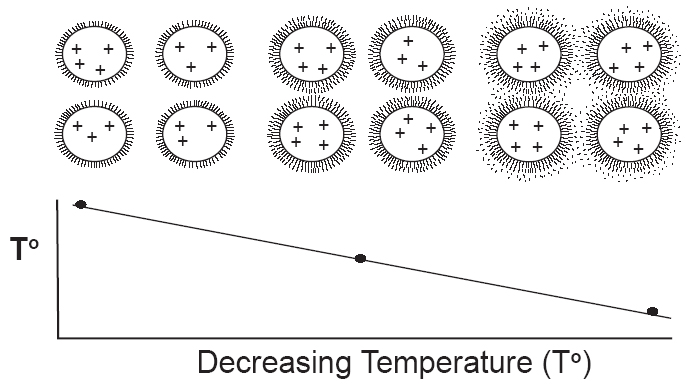

Low Temperature Seal

Figure B6:

There are indications that the thickness of adsorbed water layers on pore surfaces increase with decreased temperature (Figure B6). These layers, considered to be about 5 water molecular layers or about 13.5 nm [12] under normal temperatures (about 25oC), may increase to 8-90 layers at lower temperatures (e.g., 4oC) [11]. These results need to be verified, but they indicate that connecting pore-sizes and permeabilities would decrease with decreased temperature, implying that sedimentary formations that may not normally have seal quality might develop that quality at low temperatures.

Geophysical Indicators

Current Technology

Whereas seismic stratigraphy and seismic attribution analysis, and down-hole electrical resistivity, density and temperature logs are currently used to detect and predict SWF sources, the following factors have the potential for consideration in the future.

Geological Factors for Consideration

The six types of shallow  seals

seals are expected to have

the following characteristics:

are expected to have

the following characteristics:

(1) Clay-Rich  Seals

Seals :

Poor to moderate soft seal with a comparatively high

clay content,

:

Poor to moderate soft seal with a comparatively high

clay content,

(2) Bacterial  Seals

Seals :

Thin to reasonably thin layers of carbonate or/and

sulphide cement,

:

Thin to reasonably thin layers of carbonate or/and

sulphide cement,

(3) Gas-Hydrate  Seals

Seals :

Thin to moderately thin gas-hydrate layers,

:

Thin to moderately thin gas-hydrate layers,

(4) Uplifted Shale  Seals

Seals :

Well compacted clay-rich mudstone formations,

:

Well compacted clay-rich mudstone formations,

(5) Overpressured  Seals

Seals :

Formations with overpressured fluids being expelled,

:

Formations with overpressured fluids being expelled,

(6) Low-Temperature  Seals

Seals :

Formations with increased thickness of bound water

layers.

:

Formations with increased thickness of bound water

layers.

Geophysical Characteristics for Consideration

(1) Clay-Rich  Seals

Seals :

Reduced electrical resistivity (r)

and moderately increased seismic velocity (v),

:

Reduced electrical resistivity (r)

and moderately increased seismic velocity (v),

(2) Bacterial  Seals

Seals :

Increased

r

and v for the carbonate cement layers and reduced

r

and increased v for the sulphide cement layers,

:

Increased

r

and v for the carbonate cement layers and reduced

r

and increased v for the sulphide cement layers,

(3) Gas-Hydrate  Seals

Seals :

Increased

r

and v,

:

Increased

r

and v,

(4) Uplifted Shale  Seals

Seals :

Increased v,

:

Increased v,

(5) Overpressured  Seals

Seals :

Slightly increased porosity and v, and moderately

reduced r.

:

Slightly increased porosity and v, and moderately

reduced r.

(6) Low-Temperature  Seals

Seals :

Moderately reduced

r.

:

Moderately reduced

r.

Some Geophysical Techniques for Consideration

Electromagnetic (EM) methods, using electromagnetic coils on the sea floor, may be applicable to Item (1), part of (2) and (6). Use of discrepancies between porosities determined by down-hole sonic, electrical and density logs [7] may be applicable to Item (5). Down-hole spectral induced polarization techniques may provide useful information for Items (2), (4), (5) and (6).

Gas-Hydrate Hazard Concerns

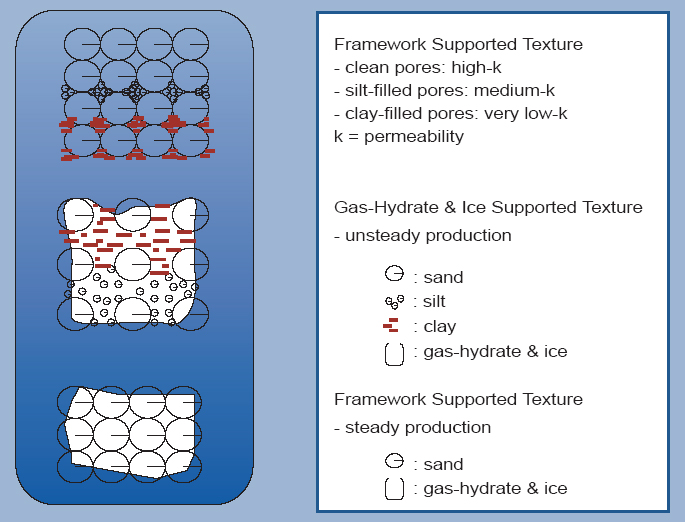

Figure C2: (Katsube et al., 2004)

Gas hydrate reservoirs can be formed under poor to

moderate  seals

seals in shallow sediments due to increased pore pressure of free

upward flowing gas [4, 5, 10], as previously indicated. These gas hydrates

formed under shallow

in shallow sediments due to increased pore pressure of free

upward flowing gas [4, 5, 10], as previously indicated. These gas hydrates

formed under shallow  seals

seals could grow and expand since they would not have

to overcome excessive overburden stress conditions (Figure C2). Subsequently,

these gas-hydrates could be buried to greater depth, such as those seen today in

the sub-arctic regime [10]. In such cases, ice or gas-hydrate supported

texture (Figure C2) would develop [5]. Whereas the gas in gas-hydrate

formations would expand when it comes in contact with sea water due to drilling

activity, gas expulsion could be very rapid [5] from gas-hydrate

supported formations since the gas-hydrate hosting formation itself could

collapse.

could grow and expand since they would not have

to overcome excessive overburden stress conditions (Figure C2). Subsequently,

these gas-hydrates could be buried to greater depth, such as those seen today in

the sub-arctic regime [10]. In such cases, ice or gas-hydrate supported

texture (Figure C2) would develop [5]. Whereas the gas in gas-hydrate

formations would expand when it comes in contact with sea water due to drilling

activity, gas expulsion could be very rapid [5] from gas-hydrate

supported formations since the gas-hydrate hosting formation itself could

collapse.

References

1: Katsube, T.J. and Williamson, M.A., 1998, Shale petrophysical characteristics: permeability history of subsiding shales: SHALES AND MUDSTONES II (ed.: J. Schiber, W. Zimmerle, and P.S. Sethi), Stattgard, p.69-91.

2: Alberty, M. W., 2000, Shallow Water Flows; A Problem Solved or a Problem Emerging: OTC 11971, the Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, Texas, May 1-4, 2000.

3: Alberty, M. W., Hafle, M., Minge, J., and Byrd, T., 1998, Mechanisms of shallow water flow and drilling practices for intervention; SPE Drilling Engineering, SPE 39203.

4: Katsube, T.J., and Jonnasson, I.R., 2002, Possible seal mechanisms in shallow sediments; Implications for shallow-water flow: Society of Exploration Geophysicists (SEG) Summer Research Workshop (SRW), Galveston TX, May 12-17 2002, Presentations and Abstracts, http//www.kmstechnologies.com/galveston%202002.htm, Session II (May 13), Abstract, Summary and 12 slides.

5: Katsube, T.J. Jonasson, I.R. Uchida, T. and Connell-Madore, S., 2004, Possible seal mechanisms in shallow sediments: and their implication for gas-hydrate accumulation: In Proceedings of AAPG HEDBERG CONFERENCE “Gas Hydrates: Energy Resource Potential and Associated Geologic Hazards” (Ed: T. Collett and A. Johnson), September 12-16, 2004, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 4p.

6: Katsube, T.J. Jonasson, I.R. and Piper, D., in prep., Possible seal mechanisms in shallow sediments; implication for shallow water-flow: Geological Survey of Canada Current Research.

7: Bowers, G.L., and Katsube, T.J., 2002, The role of shale pore-structure on the sensitivity of wireline logs to overpressure: in A.R. Huffman and G.L. Bowers, eds., Pressure regimes in sedimentary basins and their prediction; AAPG Memoir 76, p. 43-60.

8: Katsube, T.J., Bloch, J., and Cox, W.C., 1998, The effect of diagenetic alteration on shale pore-structure and its implications for abnormal pressures and geophysical signatures: In the Proceedings for the "Overpressures in Petroleum Exploration Workshop" (e.d., A. Mitchell, R.E. Swarbrick, and J. Dainelli), Elf-EP Memoire-22, April 7-8, 1998, Pau, France, 1/9-9/9.

9: Peckmann, J. and Thiel, V., 2004, Carbon cycling at ancient methane seeps: Cemical Geology, 205, 443-467.

10: Katsube, T.J., Dallimore, S.R., Uchida, T., Jenner, K.A., Collett, T.S., and Connell, S., 1999, Petrophysical environment of sediments hosting gas-hydrate, JAPEX/JNOC/GSC Mallik 2L-38 gas hydrate research well: in Scientific Results from JAPEX/JNOC/GSC Mallik 2L-38 Gas Hydrate Research Well, Mackenzie Delta, North West Territories, Canada: (ed.) S.R. Dallimore, T. Uchida, and T.S. Collett; Geological Survey of Canada, Bulletin 544, 109-124.

11: Katsube, T. J., Scromeda, N, and Connell, S., 2000, Thicknesses of adsorbed water layers on sediments from the JAPEX/JNOC/GSC Mallik 2L-38 gas hydrate research Well, Northwest Territories: Geological Survey of Canada Current Research 2000-E5, 6p.

12: Hinch, H.H., 1980, The nature of shales and the dynamics of hydrocarbon expulsion in the Gulf Coast Tertiary section:

13: Bily, C., and Dick, J.W.L., 1974, Natural occurring gas hydrates in the Mackenzie Delta, Northwest Territories: Bulletin

14: Issler, D.R., 1992, A new approach

to shale compaction and  stratigraphic

stratigraphic restoration, Beaufort-Mackenzie Basin and

Mackenzie Corridor, Northern Canada: AAPG, 76, 1170-1189.

restoration, Beaufort-Mackenzie Basin and

Mackenzie Corridor, Northern Canada: AAPG, 76, 1170-1189.

15: Ostermeier, R.M., Pelletier, J.H., Winker, C.D., Nicholson, J.W., Rambow, F.H., and Cowan, K.M., Shell International E&P, 2000, OTC 11972, the Offshore Technology Conference, Houston, Texas, May 1-4, 2000.

16: Best, M.E. and Katsube, T.J., 1995, Shale permeability and its significance in hydrocarbon exploration: The Leading

17: Hermanrud, C., Wensaas, L., Teige, G.M.G., Nordgard Bolas, H.M., Hansen, S. and Vik, E., 1998, Shale porosities from well logs on Haltenbanken (offshore Mid-Norway) show no influence of overpressuring: in Law, B.E., G.F. Ulmishek, and V.I. Slavin eds., Abnormal Pressures in Hydrocarbon Environments; AAPG Memoir 70, p. 65-85.